An Introduction to Outlaw Comics

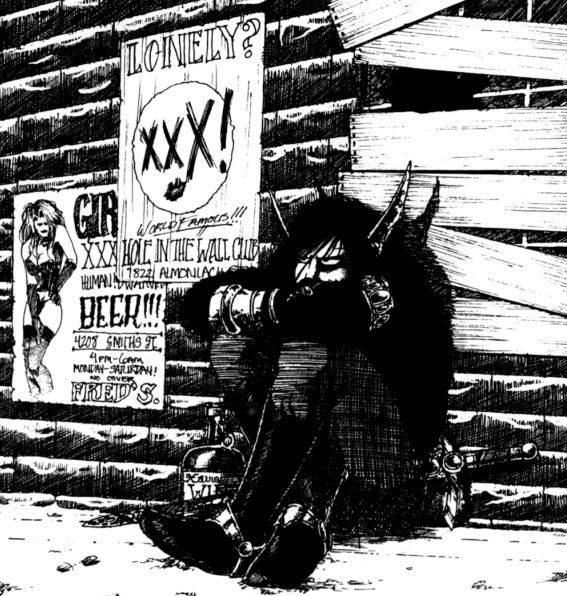

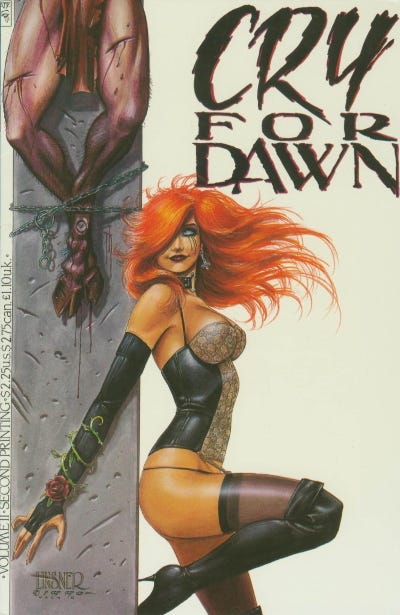

Outlaw Comics are a genre of mostly black and white, hyperviolent, sexual, bleak comic books like Faust, The Crow, and Cry for Dawn.

Content warning: this article discusses comic books that portray violence, including sexual violence, in a graphic manner. I don’t describe these things in detail in this article (though might discuss them in more detail in future articles) and have tried to keep the illustrations relatively tame, but some do contain gore and sexually suggestive images.

As a kid I loved all comic books. Superman. Groo. Captain America: Return of the Asthma Monster. Anything so long as it had sequential art. As I approached my teens, however, I developed a strong preference for darker, more macabre comics. Maybe it started with Spawn or maybe it was a more innate preference, but I found myself drawn to violence, vampires, and the occult.

But I still liked — loved even — other types of comics, including traditional superhero fare like Green Lantern and Flash. That all changed the summer after I turned 13 when I saw The Crow movie.

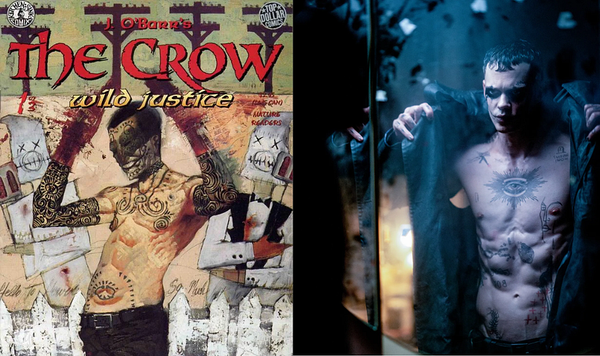

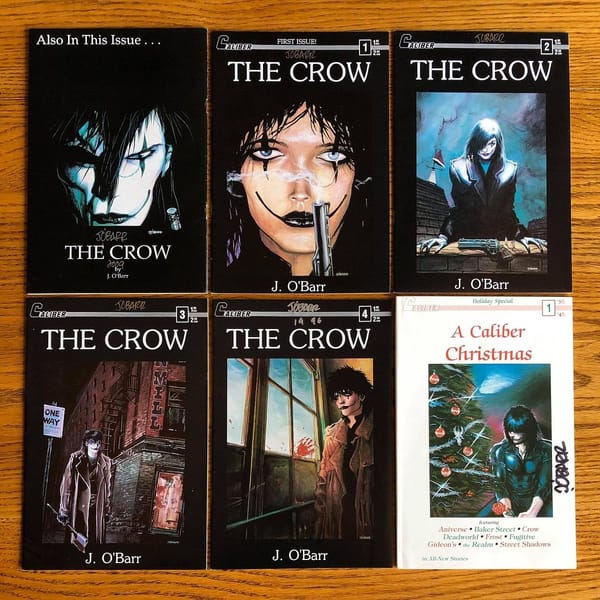

For me, The Crow wasn’t just a movie. It gave me, a loner and perpetual outsider living in rural Wyoming, a glimpse of a world I desperately wanted to be a part of. I saw in The Crow an identity. A glimpse of what I’d now call goth culture, I guess, though I didn’t know the word then. Music and clothes were a part of it. But I saw that comics could be too. I tracked down the Kitchen Sink collection of James O’Barr’s The Crow comic. I’d read O’Barr’s “Frame 137” from Dark Horse Presents, but it didn’t prepare me for The Crow. The comic was really different from the movie. It was even more violent and painful. It was like nothing else I’d ever seen.

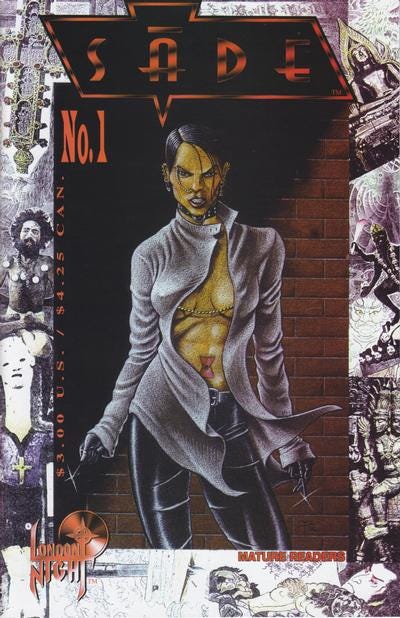

After that, other comics seemed bland in comparison. Even Spawn. I started seeking out other titles similar to or related to The Crow. Things like Poison Elves, Razor, and Golgothika. Outlaw Comics.

The late comics seller Glen Hammonds coined the term “Outlaw Comics” in the early 1990s to refer to the hyperviolent, often sexual, comics he sold, such as Faust: Love of the Damned, Cry for Dawn, and, of course, The Crow.

I don’t think I knew the term, but I sure knew the style. I picked up every comic Razor publisher London Night Studios put out for a year or two. But being a teenager living in the middle of nowhere, my options were limited. For better or worse, I didn’t hear about Hammond’s mail-order business Raw Comics until it was far too late. I don’t think I ever even saw copies of Cry for Dawn or Faust for sale anywhere, nor could I likely have afforded the high-priced back issues.

My taste in comics changed again as I got older and I all but forgot about most of these books. I wasn’t the only one. By the end of the 1990s, the term “Outlaw Comics” had faded into obscurity, along with many of the comics Hammonds championed. As the comics market collapsed, some creators left the medium entirely.

But now “Outlaw Comics” are back. Ed Piskor and Jim Rugg reintroduced the term with their popular YouTube Series Cartoonist Kayfabe in an April, 2019 episode dedicated to the genre. The pair have continued to use the term to describe comics new and old, including their own titles. Many others have taken to using the hashtag #outlawcomics on Instagram to promote their work. More crowdfunding campaigns are using the term than I can keep track of.

It’s not just the term that’s made a comeback. Since at least the early 2010s a growing number of comics professionals, including Piskor and Rugg, have started acknowledging the influence of 80s and 90s comics creators that were often shunned by critics, like the popular but often ridiculed artist Rob Liefeld. Outlaw Comics, particularly the works of Faust artist Tim Vigil and his brother Joe Vigil, are among the many artists getting a fresh look as fans and creators alike dig books out of the back issue bins.

Cartoonist Kayfabe rekindled my interest in Outlaw Comics. I’ve tracked down many comics that I was never able to find, or afford, as a teenager and revisited the few comics I already had. At first I was driven by nostalgia. But the more I looked at these comics, the more curious I became. Who made them and why? What exactly is it that binds books as different as Faust and Poison Elves together? What was it about the late 1980s and early 1990s that led to this movement? How were these comics seen at the time? What impact did they have on the medium? Why were so many people, including me, drawn to them?

I found few answers on the internet. Even as Outlaw Comics publishers sold out print run after print run, only a few got any press. Little of what had been written was available online.

Given the newfound interest in Outlaw Comics, I decided it was time to document their history and legacy. After all, none of us is getting any younger. Several key figures in the story, including Hammonds, Evil Ernie co-creator Steven Hughes, Ogre and Naked Justice artist Pete Ayala, and Poison Elves creator Drew Hayes, have already passed.

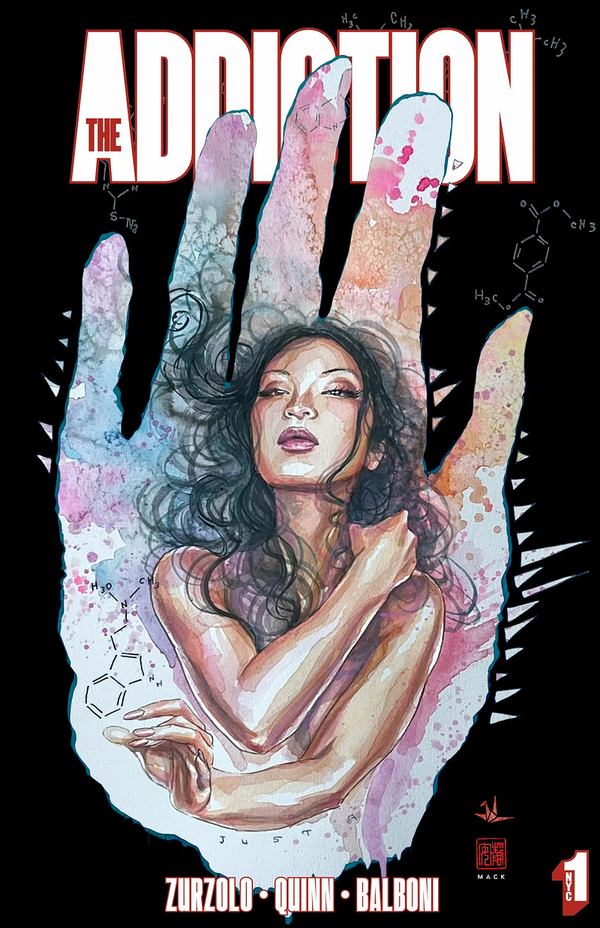

Yes, the contents of many of these books are offensive. Some are great, many are shoddy. But Outlaw Comics are a part of the history of the medium. Several successful mainstream comics creators did some of their earliest work in the outlaw trenches, including Brian Azzarello, Jim Balent, Brian Michael Bendis, Jacen Burrows, John Cassaday, Frank Forte, Kyle Hotz, Georges Jeanty, David Mack, Alexander Maleev, Ed McGuiness, Eric Powell, Duncan Rouleau, Juan Jose Ryp, and Gerard Way.

Faust and the Boneyard Press line pushed the limits so far no one could ever say again “you can’t show that in a comic.” The Crow helped give comics goth and punk cred, bringing the medium counterculture cachet it hadn’t really had since the underground era. However problematic they were, the bad girls comics that emerged out of the Outlaw scene centered female characters at a time that relatively few female characters had solo series.

This isn’t an endorsement of any particular title or creator. But Outlaw comics deserve to be remembered and understood. I won’t try to make excuses for their content, but I do hope to provide some context for their creation.

But What ARE Outlaw Comics?

The term Outlaw Comics has a life of its own now. I don’t want to, and can’t, tell anyone else how to use it. But I need to create a working definition for myself of what specifically I’m trying to document here.

I’m trying to hew as closely to Hammonds’s usage of it as possible, rather than it more contemporary usage. He defined Outlaw Comics as a “new genre of comics based on extreme violence, strong sexual situations, and very independent artistic expression” in the introduction to Razor vol. 1 issue 4. That definition seems straightforward enough, but questions quickly arise when trying to apply it. For example, what delineates this “new genre” from violent, sexual underground comix by the likes of S. Clay Wilson or Richard Corben?

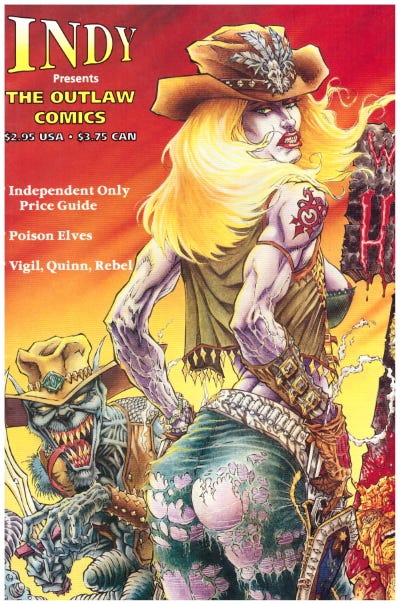

Sadly, Hammonds passed away before I could ask him these questions. Luckily he cited numerous examples of what he considered Outlaw Comics in Indy magazine # 4, published in 1994 (see the full list below). I used Hammonds’s examples as the “bible” for my research, and as a way to sort of reverse engineer some principles for what makes, or doesn’t make, an Outlaw Comic.

Hammonds also published ads for Raw Comics headlined “Dying for Outlaw Comics?” that listed many different publishers, ranging from Comico to Fantagraphics. Ultimately I think these lists were a bit too inclusive. Likewise, looking at the specific comics he sold online, which even included a few Marvel and DC titles, is a bit too far-reaching for my purposes. Sticking to his writings in Indy gives us enough examples to work with without becoming an exhaustive list of all the different comics one man liked and sold.

Piskor and Rugg’s have also made some interesting observations about Outlaw Comics that I found helpful. The following principles aren’t an exhaustive list of what does or doesn’t make an Outlaw Comic, but I’ve found them useful.

These are just principles, not rules. And again, I’m not trying to tell anyone else how to use the term. I can’t speak for Hammonds about what he meant by Outlaw Comics. I’m not going to fight anyone who calls Brat Pack an Outlaw Comic. I don’t even know whether Hammonds considered it an Outlaw Comic. But these principles have given me some guidance during my explorations.

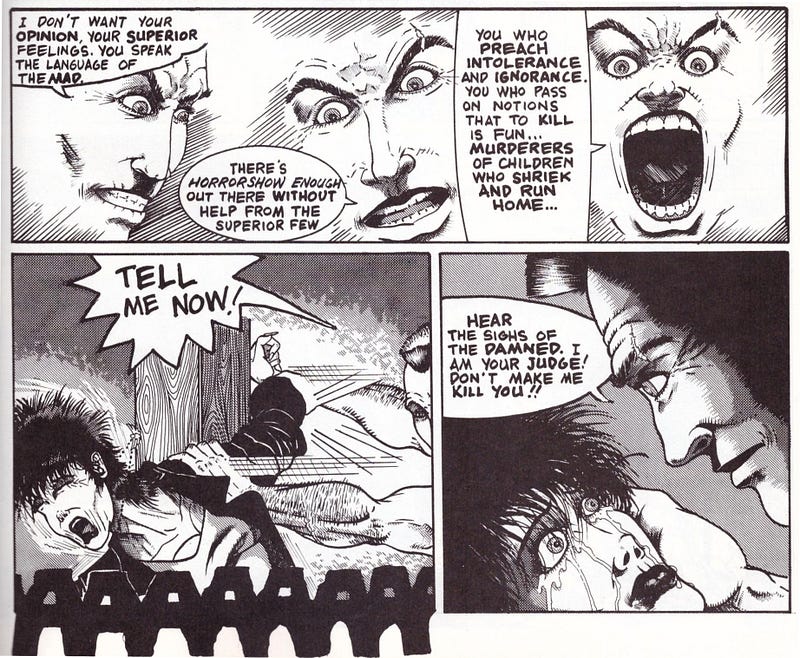

Outlaw Comics Are Dark, Violent, and Angry

The dark and violent nature of Outlaw Comics is self-evident. But more than that, they are angry. Faust writer David Quinn pointed to anger as the common thread between Faust, The Crow and many other comics. I think he’s on to something. For example, Linsner titled his Cry for Dawn collection Angry Christ Comix and subtitled it “The Angry Works of Joseph Michael Linsner.”

Hammonds picked up on that anger. In the introduction to Faust # 5, he wrote: “I see [Faust protagonist John Jaspers’s] uncontrollable demons as a symbol of America’s growing anger. Anger at gangs, multinational takeovers, and the sellout of America to anyone that can float a loan.”

Some Outlaw creators’ rage stems from personal tragedies. For others, it stems from society. For some it’s both. Politically, Outlaw creators are as divided as the rest of America. Some lean left, some right. Others keep their politics to themselves. But they are united in anger.

An exception is Hammonds’s own series Naked Justice, originally self-published as an ashcan under his own Outlaw Oracle label and later serialized in Raw Media Quarterly from Avatar Press. The sci-fi/porn/police procedural story isn’t particularly angry and though it has a horror element has little violence. Its lack of Vigil-esque hyperviolence and snarling punk posturing serves as a stark contrast to the majority of comics Hammonds promoted. It’s a porn comic first and foremost. Which leads us to our next principle.

Outlaw Comics Typically Mix Sex and Death

Outlaw Comics tend to have not just violence or sex (or at least T&A), but both either juxtaposed or mixed together. Once again Faust is the poster-child for this. The Crow has very little sex or nudity, but the few sexual scenes are violent. The original Eternity Evil Ernie mini-series didn’t have any nudity or sex but featured the voluptuous Lady Death, a character who personified this marriage of eros and thanatos.

Outlaw Comics Are Obsessive

Rugg and Piskor pointed out the obsessive nature of these books. Piskor noted the hyperdetailed nature of certain Outlaw Comics–“graphomania” as he calls it–in the Kayfabe video. “Another big part of it is the inking,” Rugg said in a Comics Journal interview. “Often, there’s more black on the page than there is white.”

I find the obsessiveness goes beyond the artwork into the subject matter, in ways that are hard to put a finger on. Themes and motifs often repeat. One obvious example is O’Barr’s obsession with opiates, particularly morphine. But it’s not any one thing. There’s a strange, obsessive energy that often leaps off the page of many Outlaw Comics.

Outlaw Creators Come From Outside the Comics Establishment

Sin City, Hardboiled, Taboo, Brat Pack, and Black Kiss all share certain similarities with Outlaw Comics, and were sold through Raw Comics. But I haven’t seen Hammonds refer to them as Outlaw Comics.

Indeed, there’s something about each of these books that seems to distinguish them from what I consider Outlaw Comics. I think a big part of it is that those books were created by established mainstream creators. Sure, Miller, Bissette, Veitch, and Chaykin were then doing independent, creator-owned books–ones that pushed many of the same boundaries that Outlaw Comics did. And it seems a little wrong to consider Bissette and Veitch as establishment in any case. But they all had a certain respectability that someone like Tim Vigil or Drew Hayes didn’t have.

There are things to quibble with here. Before The Crow, O’Barr had a four-page strip published in the black and white Marvel magazine Savage Tales in 1986. And by 1994, The Crow had been adapted into a major motion picture. Its publisher, Tundra, was backed by multimillionaire Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles creator Kevin Eastman.

But apart from Savage Tales, O’Barr had had little success in mainstream comics publishing and still worked for an auto shop in Detroit when the first issue The Crow was published by then brand new publisher Caliber Press in 1989. Veitch and Bissette fled the establishment to find freedom. O’Barr used the freedom afforded by independent comics to find his way into the establishment.

Outlaw Comics Are Outside the Realm of Good Taste

The Crow is one of the few Outlaw Comics to find much in the way of mainstream success. That has a lot to do with the contents of these comics. As Jim Rugg put it: “They’re outside of the realm of good taste. You probably are not going to show them to your mom.” Nor are they the sort of thing most people are likely to show to their coworkers or love interests. As a result, Outlaw Comics generally weren’t taken seriously, especially not by The Comics Journal, the most serious source of comics criticism at the time.

Outlaw Comics Draw Inspiration from Underground Comix

Most of the key Outlaw Comics creators, including David Quinn, The Brothers Vigil, and O’Barr, all cite underground comix as a source of inspiration. But they’re a generation removed from the underground comix. They’re a bit too young to have been a part of the underground boom and instead read those titles as teenagers. Outlaw Comics can be seen, perhaps, as carrying on the tradition of some of the darkest elements of the undergrounds, but they can’t quite be said to be of that particular movement.

Outlaw Comics Trend Towards Grit

Another way that Outlaw Comics differ from Underground Comix is that they tend towards gritty art styles and less humorous, long-form stories over the more cartoony, one-off tendencies of the undergrounds. Comics critic Ron Edwards’s notion of “grit and grot” is useful here:

Grit — authenticity about the worst moments of the human condition, and the continuing tragedy and perpetuation of violence of all kinds; season with humor, hope, or nothing as you see fit. Grot — detailed physical display, of any number of kinds, positive (minor) and negative (major): anatomical, traumatic injury, misery, sadism, orgasm, mental illness, and lots more. Explicit verbal reference counts too, especially when it’s well-timed.

If there is a stylistic transition in the mid-80s, then it’s a stronger focus on short-story and cinematic structure which I associate with the old Creepy and Eerie, rather than the Wilson-mode of crazed ‘I’m drawin’ from one corner o’the panel t’every damn other corner I kin find!’ in a terrifying blend of design-sense and detailed release (although that is never fully lost).

That rules out a number of transgressive but cartoony comics from the same period, like Mike Diana’s Boiled Angel and Chester Brown’s Yummy Fu. I think Real Deal falls right on the edge here.

Talk Outlaw With Me

I have several articles planned for this series, including a “pre-history” of Outlaw Comics covering EC, Warren, and underground comix, and a deep dive on The Brothers Vigil and Rebel Studios.

I’d love to hear from fans, retailers, creators, and publishers. What’s your perspective on Outlaw Comics and their legacy? How have they affected you? Why should people care about Outlaw Comics? Get in touch with me at klintfinley@gmail.com or find me on Instagram.

If you want to follow this series, follow Sewer Mutant here on Medium, or subscribe to my email newsletter:

Outlaw Comics Bibliography from Indy Magazine # 4

The following titles were listed in the magazine’s Outlaw Comics price guide (Disclosure: I get a cut of the profit if you buy something through these links):

- Blood Reign (Fathom) (Lone Star)

- Cry for Dawn (CFD) (Lone Star)

- Crow (Caliber) (Lone Star)

- Dark (Continuum) (Lone Star)

- Elfheim (Nightwynd) (Lone Star)

- Evil Ernie (Malibu/Eternity) (Lone Star)

- Faust (Northstar and Rebel Studios) (Lone Star)

- Flare (Hero Publishing) (Lone Star)

- Fritz Whistle (Northstar) (Lone Star)

- Gareth Blackmore’s Unusual Tales (Blackmore) (Lone Star)

- Godhead (Anubis) (Lone Star)

- Necromancer (Anarchy) (Lone Star)

- Poison Elves (Mulehide) (Lone Star)

- Razor (London Night Studios) (Lone Star)

The following titles were mentioned elsewhere in the magazine by Hammonds:

- Lady Death (Chaos) (Lone Star)

- Ogre (Black Diamond Press) (Lone Star)

- Gunfighters in Hell (Rebel) (Lone Star, or direct from Joe Vigil)

- Nightvision (Rebel) (Lone Star)

- Razorburn (Mark Beachum)

- Synapse (Mark Beachum)

- Hearteater (Emergency Productions and Miller Publishing Company)

I’m not sure Razorburn and Synapse were ever published.

More Outlaw Comics Articles:

Remembering Glen Hammonds, Outlaw Comics Patron

Outlaw Comics Prehistory Part 1: EC’s “New Trend”

Outlaw Comics Prehistory Part 2: The Problematic Legacy of S. Clay Wilson

Wave of Mutilation Part 1: Joe and Tim Vigil and the Birth of Rebel Studios

Wave of Mutilation Part 2: David Quinn and Tim Vigil and The Birth of Faust

The Crow Creator James O’Barr’s Early Years

After The Crow: The Works of James O’Barr

Inside the Rise and Fall of Cry for Dawn

On Barry Blair, Founder of Aircel Comics

The Secret Origins of Avatar Press, The Last Outlaw Publisher