Inside the Rise and Fall of Cry for Dawn

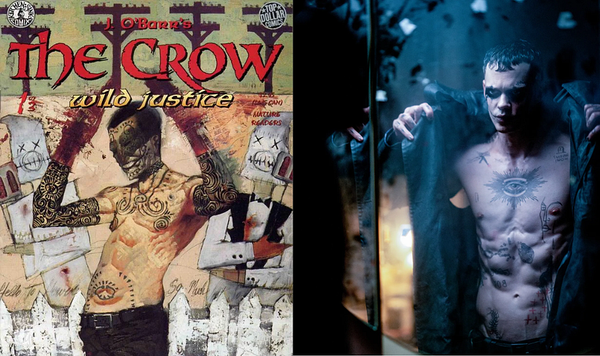

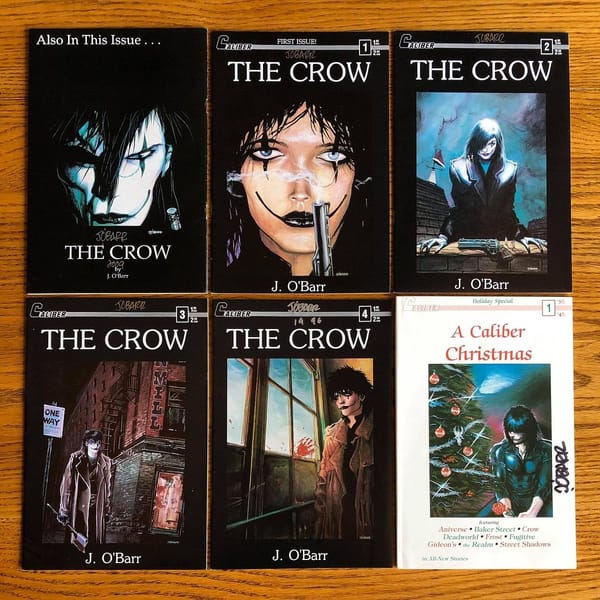

Cry for Dawn was the third of the original “Big Three” Outlaw Comics, along with Faust: Love of the Damned and The Crow.

Cry for Dawn was the third of the original “Big Three” Outlaw Comics, along with Faust: Love of the Damned and The Crow.

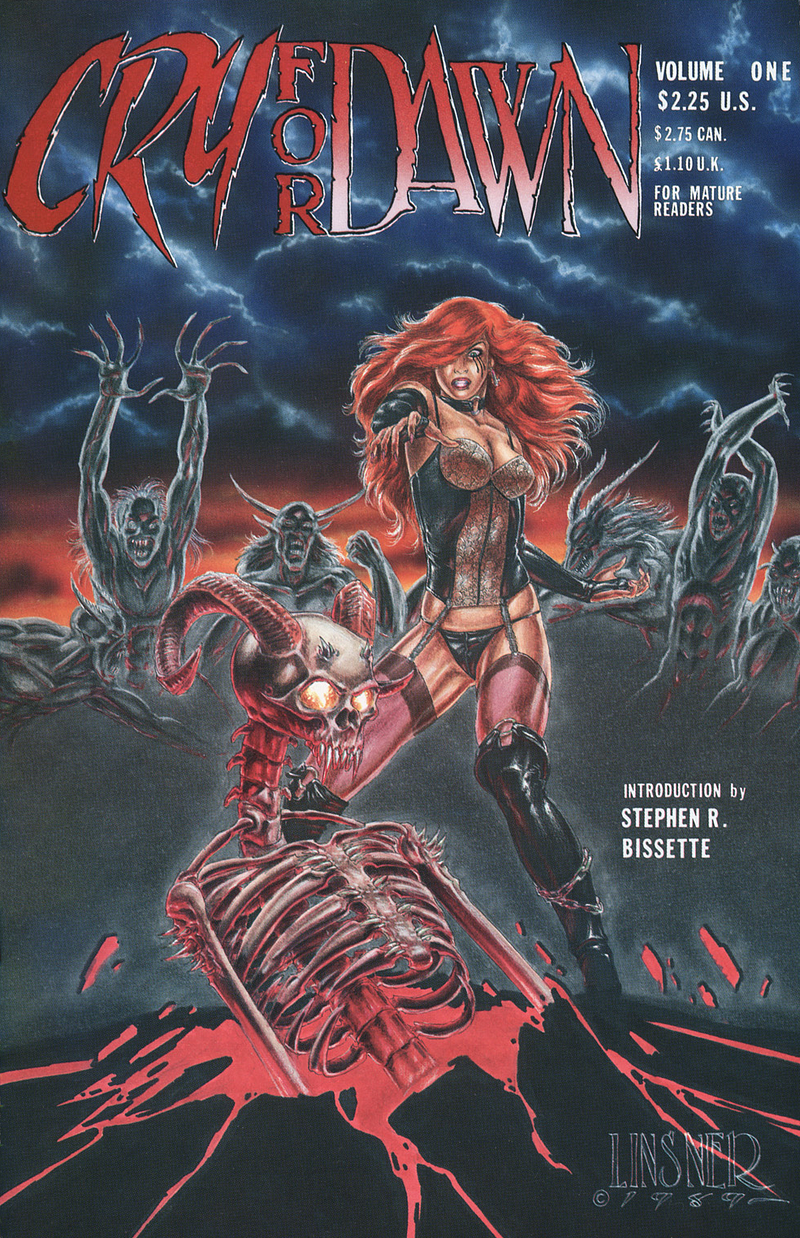

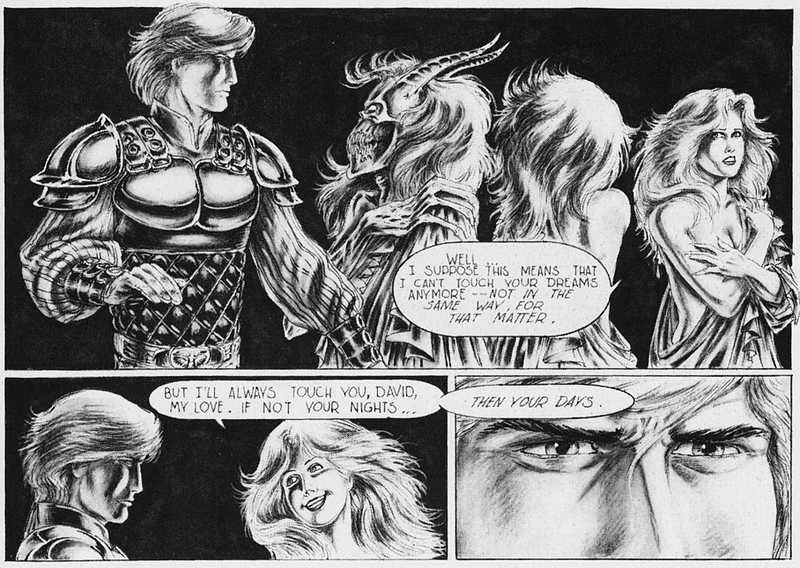

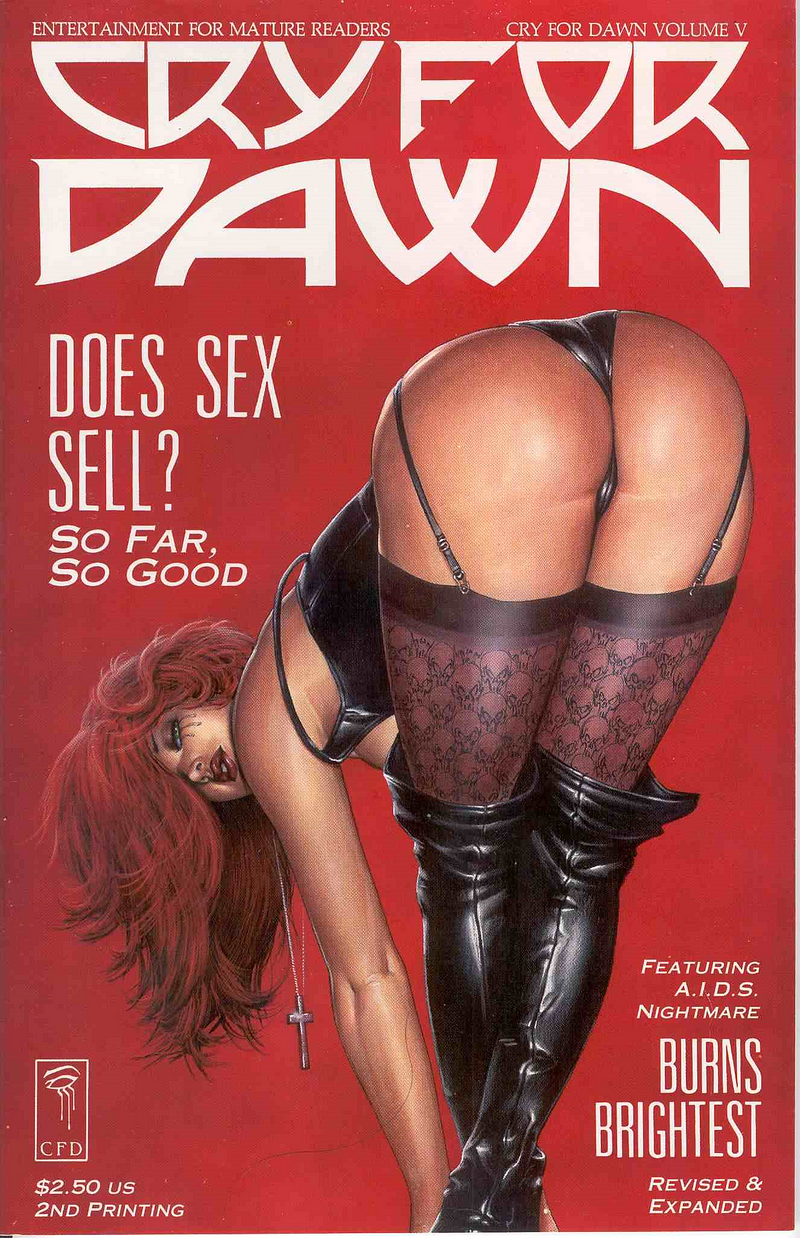

The series was a horror anthology with stories initially written by Joseph M. Monks and Joseph Michael Linsner and illustrated by Linsner. In the early issues, Linsner provided black-and-white illustrations for Monks’s stories while employing his signature photorealistic, grey-scale art for his own work. Later, they brought in other creators, but until its final issue in 1993, Monks and Linsner remained the heart of the book.

Note: Joe Monks and Joe Linsner were kind enough to provide lengthy answers to my questions. There was far more material than I could use in the article, so I’m publishing their responses in full: Joe Linsner interview. Joe Monks interview.

Right out of the gate, Cry for Dawn was pegged as part of the Outlaw Comics world. In his introduction to issue 1, Stephen Bissette compared Linsner to Faust artist Timothy Vigil and Deadworld artist Vincent Locke. This comparison makes more sense for Linsner’s pen-and-ink illustrations for Monk’s stories than for his grey-scale work, but much of Linsner’s early work shared Vigil and Locke’s penchant for graphic violence.

Linsner tells me that he didn’t feel like he was part of a “scene” with artists like Vigil, The Crow creator James O’Barr, or Razor creator Everette Hartsoe but “in retrospect, I suppose we were. We all knew each other and would chat at cons. We’d swap stories about terrible printers and that sort of thing. There was a HUGE valley between us and the mainstream guys.”

By embracing the anthology format, instead of following a specific character or set of characters, Monks and Linsner were able to explore a wider range of topics, including abortion, AIDS, racism, child abuse, and more. Monks and Linsner mined current events to create horror that reflected the era’s anxieties. Many of these stories don’t work but they capture the Outlaw Comics zeitgeist in a way no other series could.

Origins

Linsner grew-up in the New York City area. He was a fan of superhero comics like Batman and X-Men from an early age, but he also quickly discovered the more adult-oriented comic magazines of the day. “I always had a lot of fondness for horror,” he said in a 2013 interview at Emerald City Comic Con. “I grew up reading Creepy and Eerie.”

By bypassing the Comics Code Authority, these publications were able to show more violence and nudity than could be found in traditional comics of the era and were an important influence on Linsner, James O’Barr, and many other Outlaw Comics creators. In an editorial in Subtle Violents, Linsner cited “A Witch Shall Be Born” from Savage Sword of Conan # 5 as a major early influence and Roy Thomas and Tim Conrad’s adaptation of Robert E. Howard’s “Worms of the Earth” in Savage Sword # 17 as one of the few comics that had the “power to scare the hell” out of him.

As he was for so many other Outlaw Comics artists, Frank Frazetta was a key inspiration for Linsner. “I’m constantly going back to Frazetta and learning new stuff,” he said in 2013. He cited pinup artist Alberto Vargas as another foundational inspiration.

“I would sneak off and stare at [his father’s ‘girlie mags’] for as long as I could get away with,” Linsner told Sequential Tart in 2001. “All without a sexual thought in my head — I had no idea what sex was, I just knew that I was drinking in beauty. I remember looking at them and wishing that I was a girl, because girls are so beautiful.”

Linsner met Monks in fifth grade. The two shared a passion for storytelling. “From the time I was nine and found an old, portable typewriter in the back of my Dad’s closet, I’ve been churning out stories,” Monks tells me. He wrote his first novel at the age of 12. “For one of the early books, Joe [Linsner] actually did a cover,” he says.

Linsner, a self-taught artist, had tried to break into the mainstream comics industry prior to Cry for Dawn. “I would show my portfolio in the early days and then look at Marvel and think ‘I’m at least better than their worst guy, why don’t they fire their worst guy and at least hire me’?” he said in 2013. “I learned it didn’t work that way.” He did at least land a gig drawing a cover for Continuum Presents # 1 from Continuum in 1989. “I think I got paid $250, which was more than I was bringing home a week from my day job, so I was very happy with that,” he told Comicdon in 2004.

Meanwhile, Linsner and Monks had mulled over the idea of doing a horror comics anthology together. “When a friend who worked in a comic shop told us we could print a couple thousand copies for $1,500? Bingo — we were in,” Monks says.

“That sounded very achievable, so I turned to Monks and suggested that we actually do a horror anthology comic — for real,” Linsner says. “Not just putz around and talk about it, but really knuckle down and do it.”

The Birth of Cry for Dawn

The first issue of Cry for Dawn landed in late 1989, when Linsner was 20 years old. It was a big year for Outlaw Comics: the first issue of The Crow was published as was the retail edition of Faust: Love of the Damned # 1, which had originally been sold primarily at conventions or by mail order.

“Stephen Bissette is a saint because he showed us all of the nuts and bolts of publishing, and told us the smartest thing to do was just do it ourselves,” Linsner tells me. “He even wrote us an intro for free, which was so cool of him to do. I owe him so much!”

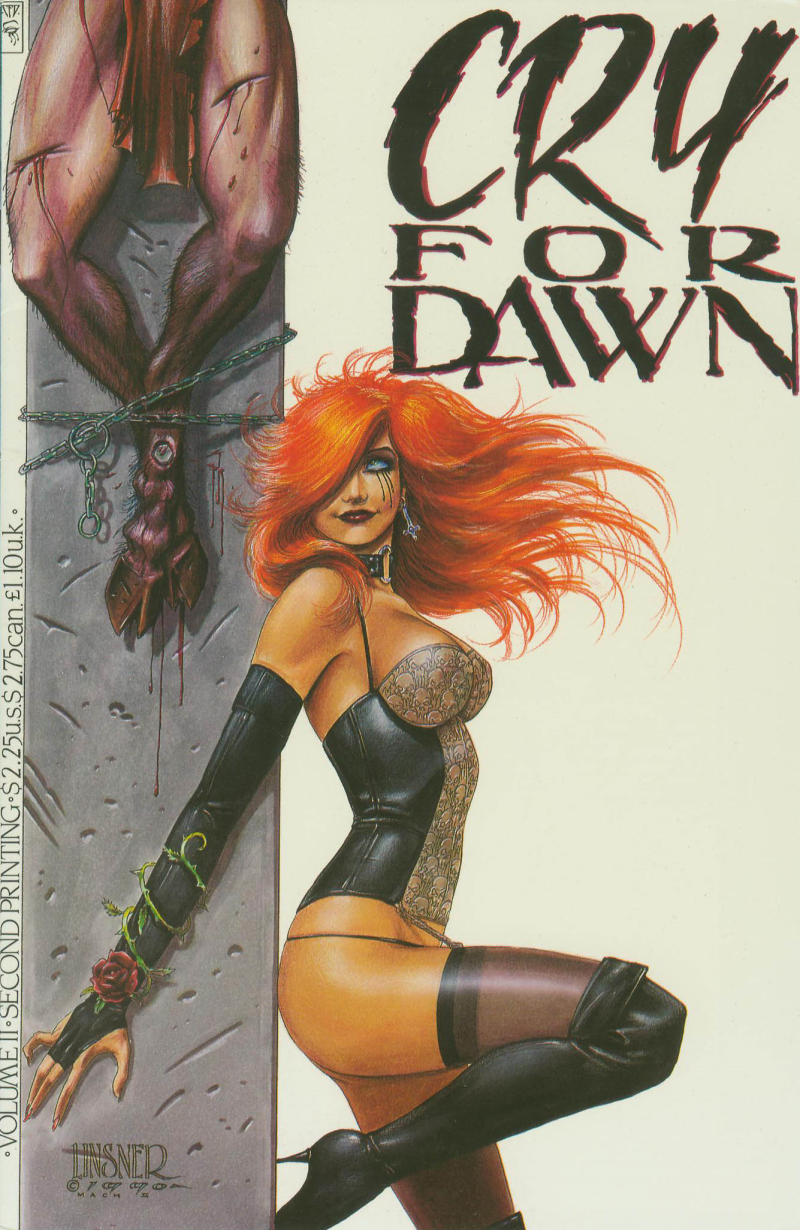

The character of Dawn actually pre-dates the anthology, at least in Linsner’s sketchbooks. “Sometimes an artist will get an idea for one little thing, but you can’t just draw that one little thing, you have to draw something around it,” Linsner said in the 1991 Cry for Dawn documentary. “The one little thing there was the [skull lace pattern Dawn is frequently depicted wearing] and she just happened to surround the lace pattern.”

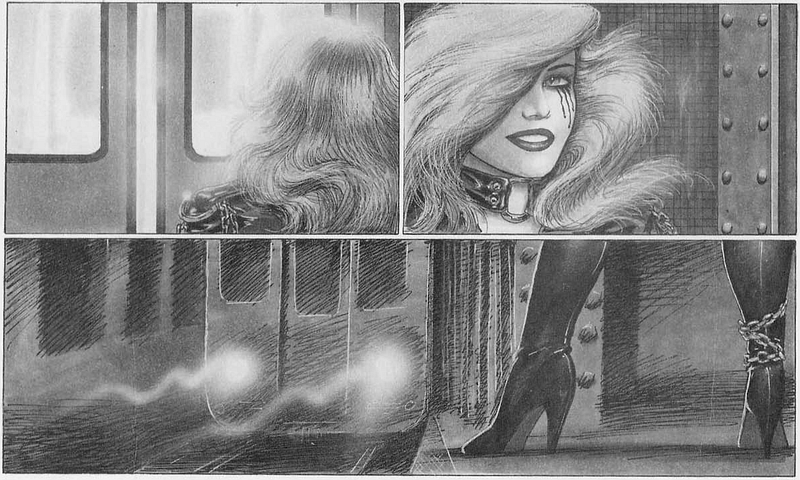

Though Dawn would go on to star in several mini-series by Linsner, she doesn’t appear as a character in the early issues of Cry for Dawn. She’s often described as a host, along the lines of The Crypt Keeper or Elvira, but she’s really more of a mascot. She plays something resembling the host only in the first issue, in brief text passages before a few of the stories. After that, she appears primarily on the covers, credit pages, and editorials. She does make a cameo in “Purity Through Fire,” from Cry for Dawn # 3, where she appears briefly on a subway car.

Linsner says Cry for Dawn was originally intended as a one-shot. “I had dozens of other things I wanted to do,” he explains to me. “A lot of my heroes, like Frazetta, Wrightson, and Corben had started out doing short horror stories, so it seemed like a nice place to start my career. ” But he wanted to branch out into other areas.

“I have no affection for the horror genre because it’s very limited,” he said in the Cry for Dawn documentary. “I’ve been growing beyond the restrictions of the genre. Cry for Dawn is not really a horror comic anymore.”

Monks, on the other hand, was all in on horror, which would eventually lead to apparent tensions between the two. “The book we do is the thinking man’s comic,” Monks said in the documentary. “Maybe the horror genre is not where you would expect to find the thinking man’s comic.”

Bissette described the book’s lofty goals in his introduction. “Somewhere in that darkness is the genuine article: horror fiction that is real, human, of substance — that explores rather than exploits, and is therefore of value,” Bissette wrote. “By looking into those shadows with unflinching clarity of vision, confronting our nightmares and fears, we may indeed find enlightenment of a kind.”

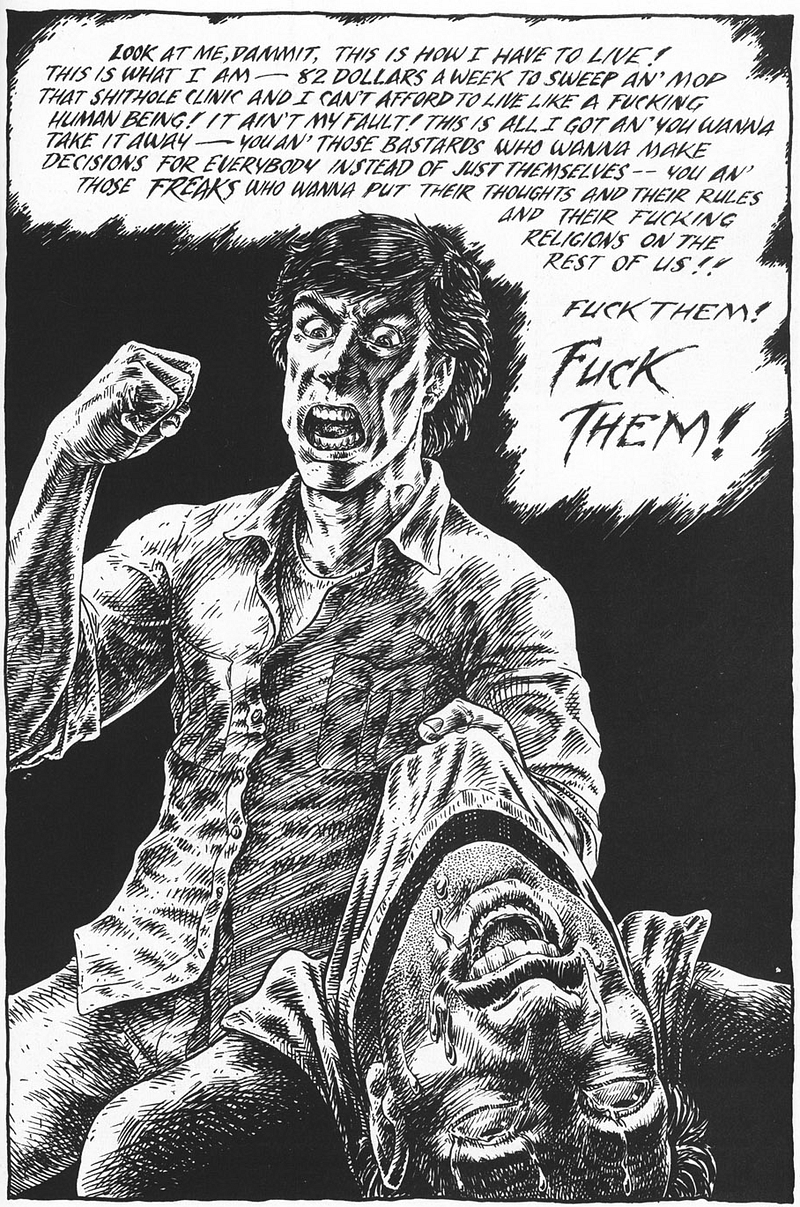

Confronting nightmares they did, but it’s arguable how much enlightenment there was to be found in their explorations. For example, the first issue has a story written by Monks and illustrated by Linsner (“Kids Meal”) about a janitor at a reproductive health clinic who supplements his meager wages by eating fetuses from the clinic. He also threatens the life of a conservative Supreme Court justice who was to cast a deciding vote overturning Roe. v Wade.

In the afterword for Cry for Dawn # 1 titled “What Scares Me,” Linsner cited ignorance and censorship as some of his top fears. “The concept that abortion might actually get outlawed again scares the hell out of me,” he wrote. “‘What about the baby, doesn’t the baby have any rights? Doesn’t the mother have any? Should she have the right to make up her mind for herself? This is America, right?”

Had Linsner not made his own views clear in his editorial in the first issue, it could easily be read as an anti-choice story. It would have been easy to walk away thinking the message was “Planned Parenthood employees are deranged fetus-eaters and the only reason abortion is still legal is because they threaten and bully leaders into keeping it legal.”

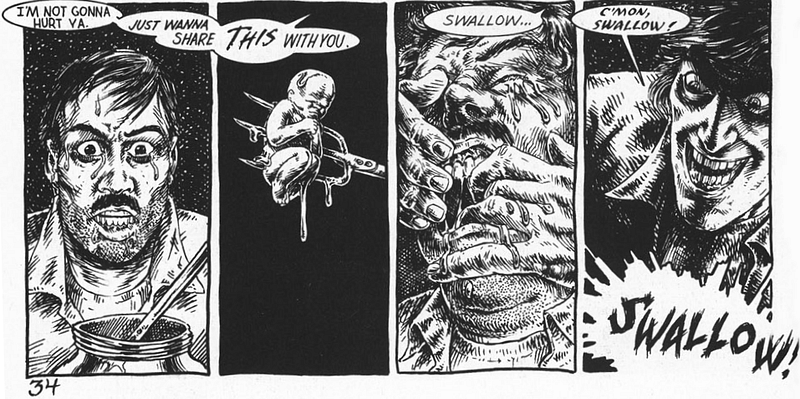

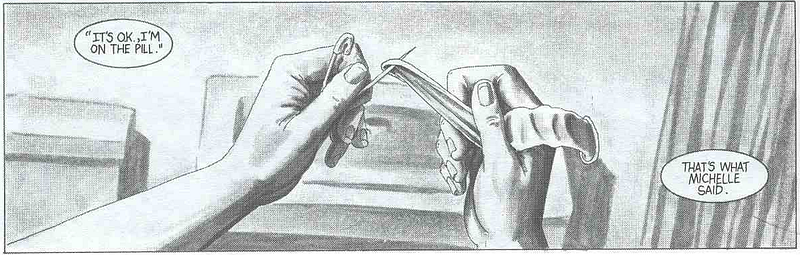

In “Burns Brightest,” written and illustrated by Linsner in Cry for Dawn # 5, a man named Jules contracts HIV from a casual sexual encounter at a party. Enraged, he goes out and sleeps with every woman he can find, hoping to spread the virus far and wide. The fact that Jules never faces any repercussions for deliberately spreading HIV makes the story all the more horrifying: the monster is still on the loose and, worse, he’s a monster you can easily imagine existing. Yet the story just doesn’t work. Neither, for example, does “Purity Through Fire,” also written and illustrated by Linsner, where a white man kills black men on the subway and eventually muses about killing the Irish next.

Monks says the reason “Kids Meal” comes across as ambiguous is that he had no agenda. “Thing is, that story champions no ‘side’, has no ‘cause,’ and it’s simply subject matter that was in the news at the time,” Monks says. “We didn’t want to look preachy for sure, but I also didn’t want to alienate that big a percentage of our audience.”

About “Burns Brightest,” Linsner says “The whole situation is horrible, which is why I thought of it as a horror story.”

“There is no ultimate clean resolution,” he says. “I suppose the story wasn’t 100% successful, but lots of people read it and got everything out of it that I intended. It’s all a work in progress, but if I did that story today I might be more direct. ‘Purity Through Fire’ was a failed experiment. I have not reprinted it, and probably never will. ”

Provocations

Cry for Dawn often reads as boundary-pushing for the sake of pushing boundaries, rather than to deliver a particular message. In the introduction to issue 3, Monks explained that he asked the artists on a horror comics panel at FantaCon in Albany, New York whether there was anything they wouldn’t draw. “Gahan Wilson said he really wouldn’t be interested portraying unnecessary harm to characters without resolution,” Monks wrote. Bissette said he wouldn’t draw child abuse. That issue, which included the child abuse story “Playmates” along with the above-mentioned “Purity Through Fire,” touched on practically everything that the panel of artists said they wouldn’t do.

Again, Monks emphasizes that he didn’t try to push particular messages in his stories. “The tale always has to stand on its own and make people think,” he says. “You can’t do that just pandering.”

At the time, pushing boundaries was often the message. There was a palpable sense that censors were closing in. Publishing outrageous, taboo-breaking material was often seen as a way of fighting back.

It’s easy to forget how precarious freedom of speech felt at the time, especially in comics. The Comic Book Legal Defense Fund had just been founded in 1986, following the prosecution of the manager of the Illinois comic shop Friendly Franks for selling comics like Omaha the Cat Dancer and Weirdo. Indie publishers like Bissette reportedly had issues with printers who refused to print their work. Comics like Faust and Cry for Dawn were routinely seized by customs agencies when exported to Canada, the UK, and other countries. The Comics Journal issue 143 (April 1991) reported that Cry for Dawn was banned entirely in New Zealand, along with Milo Manara’s Click, the Pander Brothers’ Exquisite Corpse, and Barry Blair’s Sapphire.

Outside of comics, Thomas Radecki (later convicted of sexual misconduct) and the National Coalition on Television Violence crusaded against violence in media. Tipper Gore and the Parents Music Resource Center campaigned for warning labels for music with explicit lyrics, leading Walmart and many retailers to stop carrying albums that carried those labels and to the arrest and failed prosecution of Dead Kennedy’s singer Jello Biafra for making “harmful matter” to a minor.

“That was big Al Gore’s wife using government weight to censor artists she didn’t like, and we fought like hell,” Monks says.

Many of the topics explored in Cry for Dawn are relevant again today. Hate crimes are on the rise. Roe v. Wade has been overturned. Conservatives fight to keep graphic novels like Gender Queer, The New Kid, and Persopolis out of schools, and possibly even out of bookstores, often using false narratives about “critical race theory” and “grooming.” Gender Queer has been a particularly hot target, with politicians in Virginia going so far as to Gender Queer author Maia Kobabe, publisher Oni-Lion Forge, and Barnes and Noble for obscenity. The case was recently thrown out.

Much like Tipper Gore and the PMRC, they often claim that they just want to keep age-inappropriate content away from children and out of public schools, but the movement is also pushing to keep these books away from adults as well. Most famously, a town in Michigan went so far as to vote against funding the public library after librarians refused to entirely remove the book, which had originally been stocked in the adult section but later moved behind the counter and available only to those who request a copy. The library will stay open for now thanks to a successful GoFundMe campaign, but its long-term future is still in question.

Meanwhile, activists have pushed for Gender Queer to be removed entirely from public libraries in places including Wake County, North Carolina (which includes Raleigh and much of the “Research Triangle”); Liberty Lake, Washington (a suburb of Spokane); and Pella, Iowa. They’ve been unsuccessful so far, though the book was temporarily removed in Wake County. Librarians have been targeted for harassment and politicians are also trying to find ways to retaliate against them legislatively. For example, the Indiana state Senate passed a bill that would have enabled the prosecution of both school and public librarians who stocked supposedly objectionable books (the bill died in the state House).

“I still hate all censorship, and I’m in shock that we’re going backwards on Roe v. Wade,” Linsner says. “The controversy over ‘critical race theory’ is an embarrassment to our nation. Slavery happened. Racism happens. There’s no denying it. ”

Monks, on the other hand, says he understands the plaintiffs suing Kobabe and Oni-Lion Forge. “I can sympathize on the Barnes & Noble front, but elsewhere? Less so,” he says. “There’s a difference between a ban and having age restrictions.”

“You don’t want Gender Queer being checked out by 12-year-olds without permission at school? Cool,” Monks continues. “You want your kid to have access? Get it out of the regular library or buy a copy.”

That assumes copies will be available at your local bookstore or library — and that your library still exists.

Breakout Success

I’ve been pretty hard on Cry for Dawn up to this point, but comparing it to Bissette’s own horror anthology Taboo is illuminating. Bissette assembled some of the best creators in the business, ranging from underground comix legends like S. Clay Wilson and Rick Grimes to alternative comics talents like Charles Burns and Chester Brown to, well, to Alan Moore. While almost all of Taboo’s entries are excellent graphically, many of them are unsatisfying as stories.

Taboo had a far better batting average than Cry for Dawn, but its number of misses underscores just how hard the short horror anthology format is to do well, even with the highest caliber creators available. The most enduring story from Taboo isn’t a short work: it’s Moore and Eddie Campbell’s serialized From Hell, which eventually weighed in at 512 pages including end-notes.

The comics buying public was certainly interested in Cry for Dawn. The first issue sold through three printings and the second issue sold through two. Wizard reported in 1997 (issue 67) that a counterfeit copy of Cry for Dawn # 1 was circulating, demonstrating the incredible demand for copies of the book.

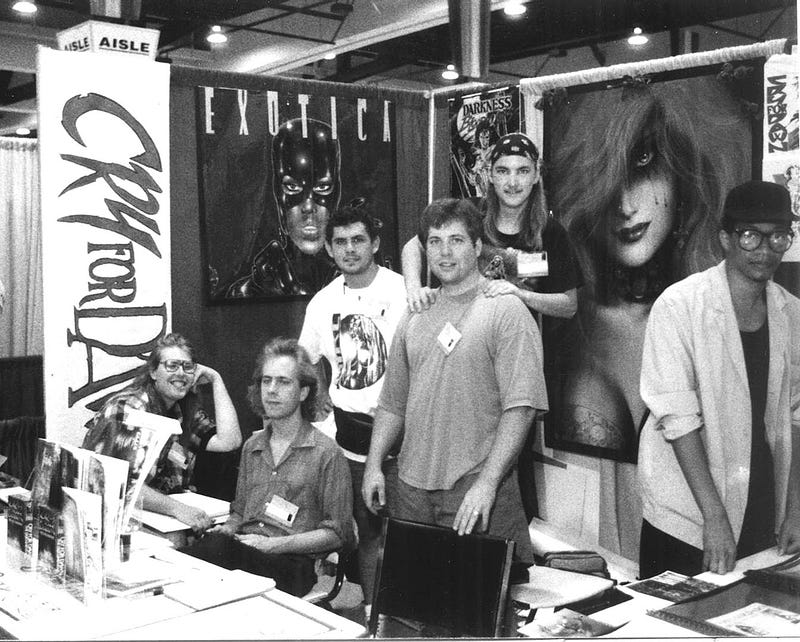

The book received relatively little press, even compared to books like The Crow and Faust. “We did 10 gazillion conventions trying to spread the word,” Linsner tells me.

Around the time the second issue came out, Monks and Linsner met comics seller Robb Horan, owner of The Real World in Andover, New Jersey.

Horan got his start in the comics business while still in high school in 1978, working for the distributor Comics Unlimited in Staten Island. Then he went to film school at New York University. “After college, I thought I was done with comics,” he says. “I worked in film and television in New York City. Then in the late 80s, the market fell out.” Horan turned to selling comics and collectibles to supplement his dwindling income.

“I was interested in Cry for Dawn because I could sell it,” he says. “I was buying piles and piles of stuff from them.” Soon, he became CFD’s marketing director.

“He saw cinematic potential in Dawn and Cry For Dawn,” Linsner tells me. “The dream was to do an anthology movie like Creepshow, with Dawn acting as hostess. It made sense to start off small with a short film. ”

That idea led to the live-action Cry for Dawn commercial, which was released in mid-1991, between the release fifth and sixth issues of Cry for Dawn, and the documentary. “We would offer it for free to comic stores who would pay for the airtime and put a blurb at the end,” Linsner explains. Altered Images in Stanton, California and Bookcom in Baltimore, Maryland both took them up on the offer.

“It ran during Friday night movies, during the MTV awards, it got a lot of attention,” Horan tells me.

Two years later, Malibu would launch an advertising campaign for the launch of their Ultraverse comics line, and Image and Valiant would promote their Deathmate cross-over on the then-nascent Sci-Fi Channel. But in 1991, it was rare for comics publishers to advertise on television. “It seems too obvious to me that if a good product wants to compete with the big money standards, then TV advertising becomes far and away the best method to reach the largest new audience,” Horan wrote in Cry for Dawn issue 6.

“We had no way to quantify if it increased sales of the book,” Horan tells me. “But we also packaged and sold the commercial on VHS so we came out ahead.”

The Growth Years

In addition to bringing on Horan, Linsner and Monks expanded the line of comics published under the CFD banner in 1991. The comics speculation bubble was inflating and the Outlaw Comics explosion was well underway. New publishers inspired largely by the likes of Faust, The Crow, and Cry for Dawn sprung up the same year, including Hart. D Fisher’s Boneyard and Everette Hartsoe’s London Night Studios. Rebel Studios was expanding with Dog and Raw Media Mags. Drew Hayes began publishing I, Lusiphur. Harris resurrected Vampirella and Brian Pulido and Steven Hughes introduced Lady Death in the pages of Evil Ernie, planting seeds for the later “Bad Girls” craze.

Linsner and Monks started publishing other creators’ work, starting with Cry for Dawn # 4, which featured work by Frank Forte, Michael Dubish, and C.D Regan. “Frank Forte was living up in Connecticut and we met up with him at a show, and when I saw his work in ‘Dead Thing,’ [later published in Cry for Dawn # 6],” Monks says. “That was the first story we decided to run that Joe didn’t draw.”

CFD’s second title was an anthology called Subtle Violents, published in fall of 1991. The book gave the crew a chance to explore fantasy, as opposed to horror. In addition to Linsner, the book featured work by Thomas Derenick, Kevin J. Taylor, and Tim Conrad.

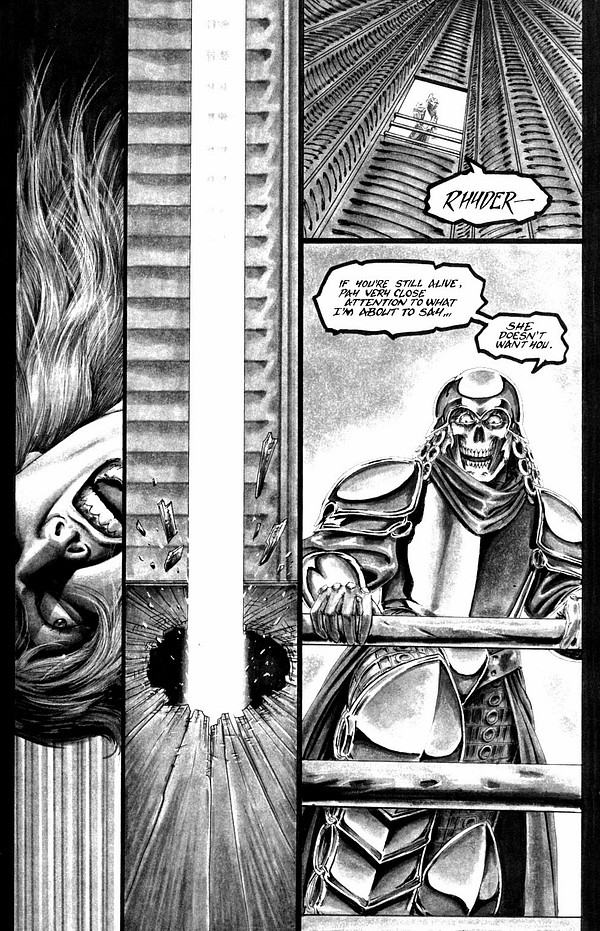

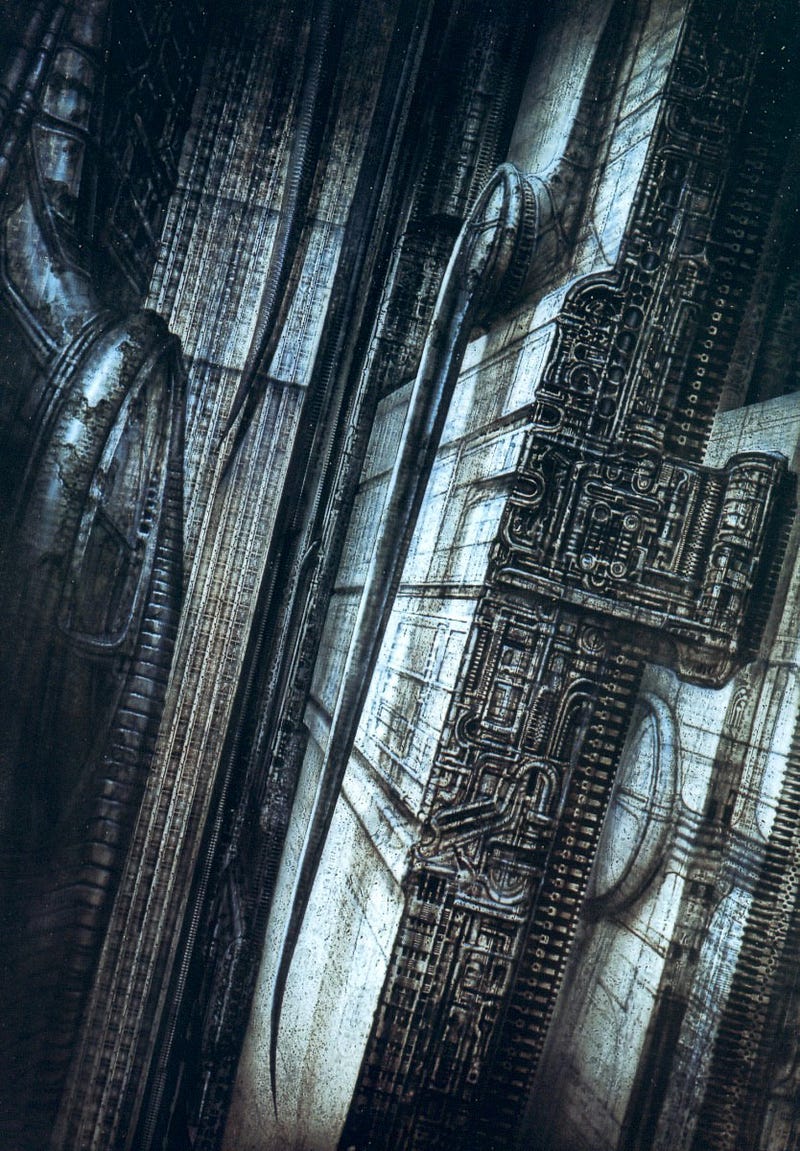

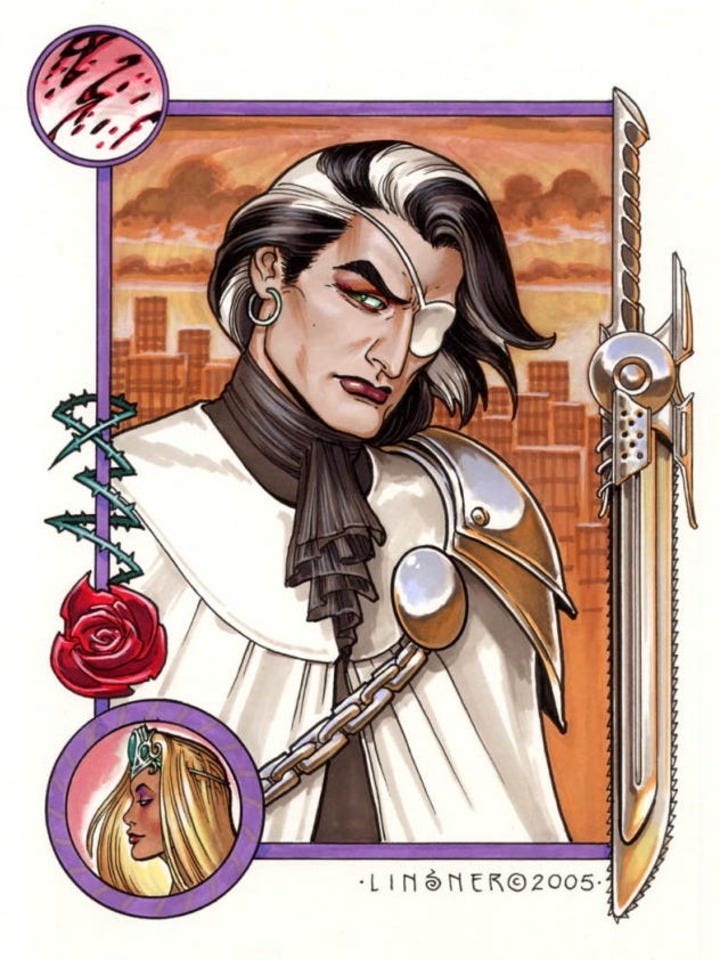

Some of the imagery we’d later see in the Dawn series showed up as early as “Bring Me a Dream” in Cry for Dawn # 1 and in many covers, back covers, and interior art pieces. But Linsner’s “Rhyder” in Subtle Violents feels like the first full appearance of the post-apocalyptic New York seen in Dawn — in fact, Darrian from the Dawn series was to appear in the never published Subtle Violets # 2.

In early 1992 CFD published From the Darkness: Blood Vows # 1, written by Ed Polgardy and illustrated by Jim Balent, a relative newcomer at the time who would soon achieve superstar status on DC’s 1993 Catwoman series. The mini-series was a sequel to a previous From the Darkness mini-series published by the Malibu imprint Adventure Comics in 1990. CFD also published Girl: Rule of Darkness by Kevin J. Taylor, creator of a series from Rip Off Press called Model By Day. That summer CFD added Richard Kane Ferguson’s Offerings and Taylor’s anthology Exotica, which continued the story from Model By Day, to the line-up. Model By Day would later be adapted into a Fox television movie starring Famke Janssen with executive producer Jeph Loeb.

“Once we released one book, lots of people started pitching,” Monks says. “Didn’t always go well, but we really wanted those creators’ books to succeed, that’s why we took the risk on them.”

The expansion was driven largely by the convention scene. “We met Kevin Taylor, an NYC local, and his samples floored us,” Monks says. “For the most part, that’s how it worked. We got tipped to Jim Balent and Ed Polgardy by a buddy with a comic shop in Pennsylvania, Tom Barnes, just when they’d started releasing Blood Vows.”

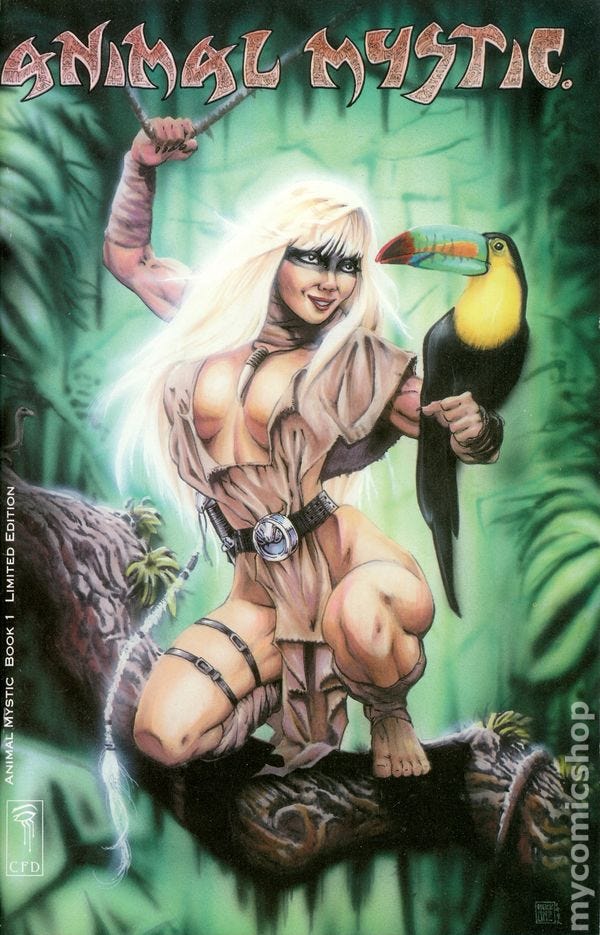

CFD kept expanding in early 1993, with Lance Tooks’s Danger Funnies as well as two collaborations by Horan and Greg “Dark One” Williams: the Safety-Belt Man Special Breakthrough Edition and Animal Mystic. “I brought Dark One into the fold,” Horan tells me. “We were at a convention at Washington, DC, where Greg won a contest they had. I bought his art and we built a relationship from there.”

Safety-Belt Man was a surreal meditation on life and death (mostly death) told through the misadventures of a crash-test dummy and an automotive engineer he has a crush on, while Animal Mystic was one of a long tradition of “White Jungle Queen” stories dating back to characters like Rima the Jungle Girl and Sheena, Queen of the Jungle.

“Animal Mystic all comes from a series I started way back in 1988,” Dark One said in interview with the Philadelphia public access television series The Comic Book Show in 1993. “I was 18 years old. She started out as a secondary character, and for some reason I started focusing on her and created a storyline and here she is.”

“Greg created Animal Mystic, I wrote it based on where he wanted it to go,” Horan says. “It was clear what a fantastic illustrator he was, what a huge imagination he had. But his ideas were all over the map. I took over as writer to bring some focus to the project.”

“He fit in with us because he was good enough for the mainstream but was too weird for it,” Linsner says. “That chasm is what drew the Cry For Dawn guys together. Kevin Taylor, Lance Tooks, and Richard Kane Ferguson are all VERY accomplished artist/writers. We were all just out of step with the mainstream in the early 90s.”

“I’m still proud of the books we put out, and I still feel that brotherhood,” he continues. “I feel like we went through the ‘comic book wars’ together. We shared something truly special, and I love them for it. I have nothing but good things to say about anyone in that bunch. ”

One CFD Ends, Another Begins

Monks and Horan waxed optimistic about the future of CFD in the Comic Book Show interview, which was filmed at the Philadelphia ComicFest held October 8–11, 1993. Taylor’s Model By Day had just been picked up by Fox, Balent was getting more recognition for his work on the Vampirella: Dracula War mini-series, and CFD had its second hit series in Animal Mystic. Monks announced a partnership with London Night Studios. “It’s an anthology project that’s going to get all the ‘outlaws’ as we’ve been described — that’s not my term but people have described us as the outlaws of independent comics,” Monks said. “We’re going to try to replace what Taboo was and what System Shock [an anthology published by Tuscany Press in 1993] wants to be in the market. A large book of independent creators getting together doing what they want in their genres.”

In reality, however, the original incarnation of CFD was on its last legs.

Horan left CFD soon after to start his own publishing company, Sirius Entertainment. “Sirius was created primarily because of Safety Belt Man,” Horan tells me. “Linsner was very supportive, encouraging me to do more writing, to create stuff. But the relationship between the Joes was deteriorating. I was about to put my heart and soul into this book I was writing and I didn’t think I could take the risk of doing the book at CFD when they were struggling with the future. I don’t think it even occurred to me to take Safety Belt Man elsewhere, self-publishing just seemed natural.”

Linsner and Monks split in October of 1993 — before The Comic Book Show interview aired in November.

“We grew apart and wanted to do different things,” Linsner explains. “He was still into horror, and I had gotten it out of my system. Cry For Dawn was a very cathartic experience for me. After nine issues of horror, I felt the venom leaving my soul. I love so many different types of stories, and I wanted to explore. ”

“Also, I grew to really dislike the rep we were getting,” he continues. “We’d go to a con, and someone would always say, ‘Man, you guys are fucked up! You’re totally whacked out, man!’ That was amusing at first, but I did not want that to be my whole career.”

Monks, meanwhile, thought the book was drifting away from what made the it so successful in the first place. “We were going in different directions on our baby — a hardcore horror title,” Monks says. “I have nothing against fantasy and dark fantasy, but Cry For Dawn was a horror title. That’s what made it, and by issue 8 that was getting lost.”

The business side was a struggle as well. They had solicited the Cry for Dawn compilation book multiple times, but kept having to cancel it. “Obviously ‘compilation’ means stuff we’d already released, but things kept needing touch-ups,” Monks says. “Other ‘issues’ kept coming up, and once you’d canceled a title three times? Orders went poof. Over thirty grand into the dumpster. That, plus the lead time between issues had grown to such an extent that we were losing fans.”

“Running a small business with very little cash flow is really tough,” Linsner says. “We couldn’t keep it together, so it all ended. ”

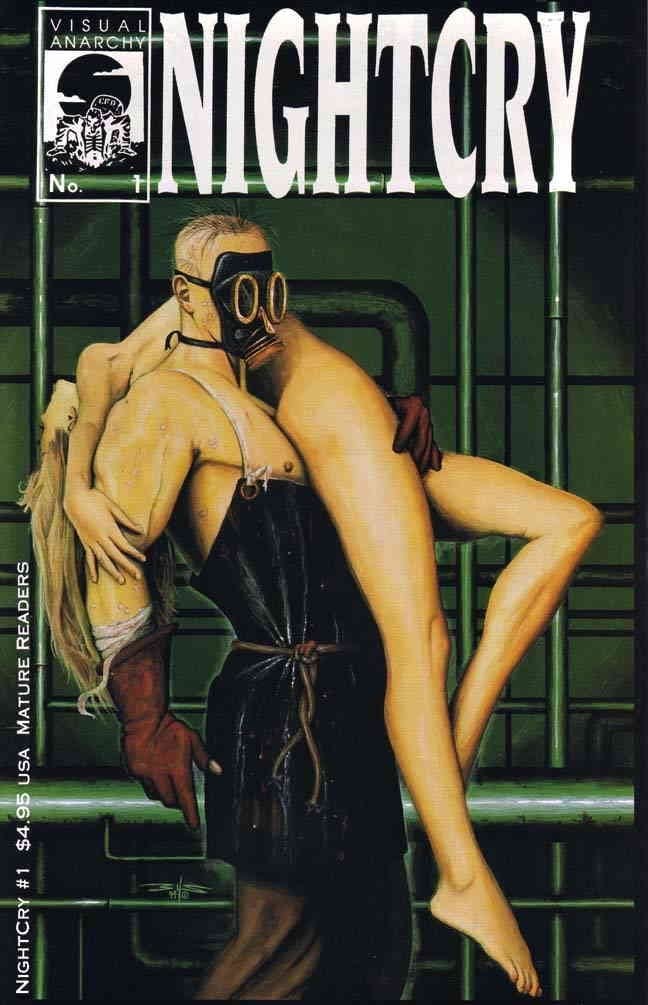

Monks continued with the horror-anthology format with Night Cry, published under the moniker “CFD Productions,” a “backronym” for Creative Forces Design & Production. The first issue of Night Cry was, as promised on The Comic Book Show, a sort of a who’s who of Outlaw Comics at the time. It contained:

- A teaser for the 1994 Razor ongoing series, written by Everette Hartsoe with pencils by Ed McGuinness and inks by Jack Slattery (plus a pin-up inked by Faust inker/Fathom Press publisher Tim Tyler).

- An Evil Ernie story written by Brian Pulido and illustrated by Leonardo Jimenez.

- A story written and illustrated by Hart D. Fisher.

- A preview for Heartstopper by Steve Roman and illustrated by Vampirella artist Louis Small Jr.

- Stories by Monks illustrated by Ken Meyer Jr. and Thomas O’Connor.

- A back cover by frequent Rebel Studios collaborator Hannibal King.

Fisher continued to contribute the occasional piece to Night Cry, and Faust writer/co-creator David Quinn wrote pieces for later issues as well. But the series had fewer big names as it progressed. That’s probably for the best. The first issue felt more like a collection of teasers for other books, while later issues featured more stand-alone stories and felt more like a true successor to Cry for Dawn.

Creative Forces Design & Production also published a new Scimidar mini-series by R.A. Jones, Noir Quarterly featuring relatively early work by Brian Michael Bendis (then known mostly for his Caliber Comics series AKA Goldfish), and the magazine Lacunae, which included a mix of original comics, prose, and interviews with the likes of Neil Gaiman, Nancy Collins, Ellain Lee, and David Lapham. Forte was a frequent contributor to Creative Forces Design & Productions, which published his Warlash and Vampire Verses. He has continued creating and publishing comics through his company Asylum Press even after his career in animation took off.

Creative Forces Design & Production was renamed Chanting Monks Press in 1998 because the old name was a bit too long. “John Orlando gave me this sketch of a concept he’d been working on right about the time the B&W indie market hit bottom, and I decided keeping the initials didn’t matter anymore,” Monks says. “Chanting Monks Studios was much shorter, and the monk logo fit.”

Chanting Monks went on to publish the Monks-edited horror anthology Zacherley’s Midnite Terrors, the Bad Girl/zombie apocalypse series Gory Lori, and most notably a few works by Bernie Wrightson, including an anthology called Night Terrors that included a story by Wrightson, and Stuff Out’a My Head, a short story collection with illustrations by Wrightson.

“Bernie was a guest at a Chiller Expo and we hung out,” Monks says. “He loved the idea of having stories interwoven with an art portfolio, and I’d never seen one. I told Bernie: ‘Why not us?’ So we ran with it. He was the kind of guy you could work with and never have a disagreement. Didn’t mean you were always on the same page, and sometimes we went back and forth on how to get something across, but disagreements? Never.”

Monks lost his vision in 2002. In 2011, he released The Bunker, billed as the first movie by a blind director. “I had a feature script that I thought would be easy to shoot. Not for me, but for a team of indie filmmakers. Y’know, people with sight,” Monks says. “I walk into my wife’s office and tell her: ‘I’m going to direct a film. Blind. It’s never been done before.’ She sits there for a minute, and I think she’s about to tell me I’m nuts, but then she says: ‘Okay, How?’”

Monks still publishes prose and recently crowdfunded a new horror comics anthology called Sickk ‘N Twisted, featuring the return of Gory Lori.

Dog Star Rising

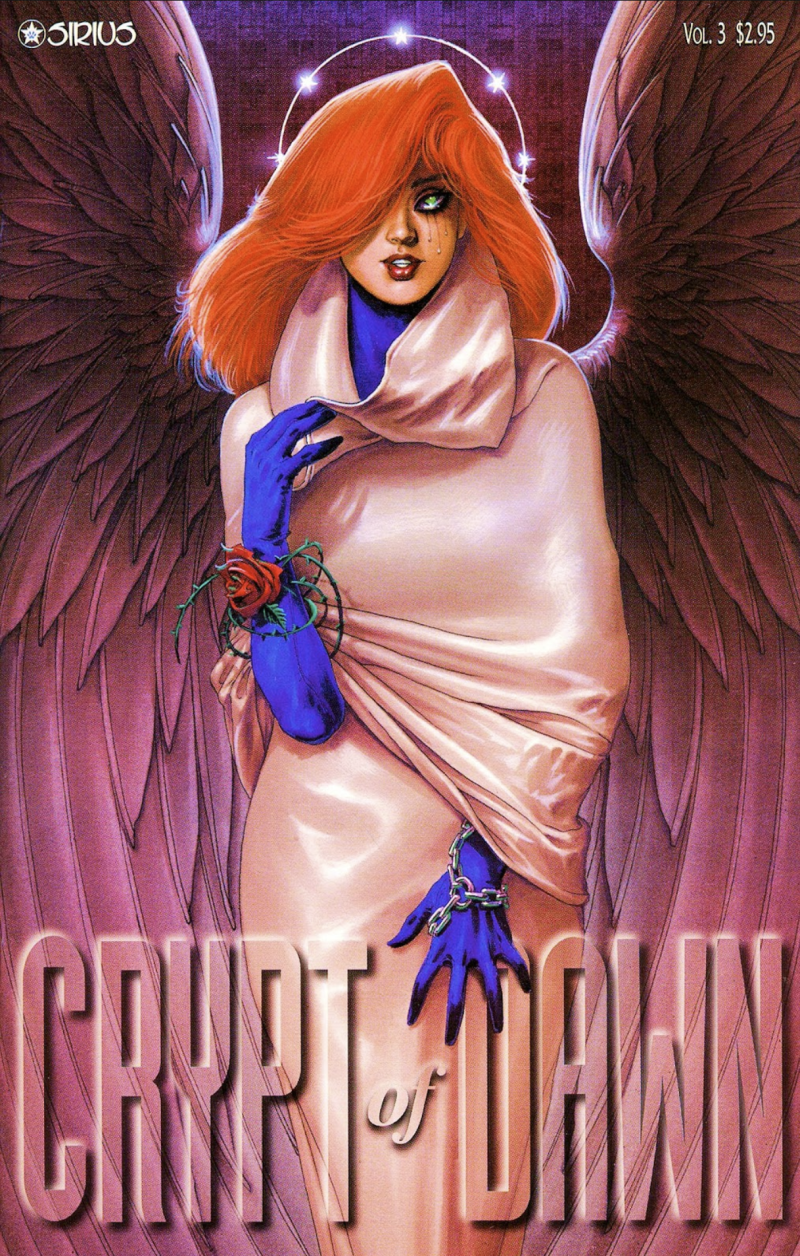

Linsner jumped ship to Sirius, becoming the budding company’s art director. Sirius launched in May, 1994 with Angry Christ Comix, a collection of Linsner’s Cry for Dawn stories.

“I thought about starting my own company, but I wanted to pull back from the running of a company and just concentrate on my own comics,” Linsner says. “At Cry For Dawn I did ALL of the production art chores on every title we published — putting together the ads, pasting down the typesetting, laying out the mechanicals. It was a mountain of work. At Sirius we had artist and computer whiz Mitch Waxman doing most of that because the world was switching from analog to digital — desktop publishing was becoming the affordable norm. So it made sense at the time to join forces.”

Taylor and Dark One migrated to Sirius as well, with Animal Mystic, Safety Belt Man, and Model By Day following that summer.

Linsner’s first new work for Sirius was Drama, which was a sort of prequel to the Dawn series, which didn’t debut until the summer of 1995. It was that same summer that Hayes brought his dark fantasy series Poison Elves to Sirius.

But that’s a story for another article…