James O’Barr Part 2: The Crow and the Caliber years

A look at James O’Barr’s most productive period as a comic book artist and the legacy of his masterpiece, The Crow.

The Crow and the Caliber Years: James O’Barr Part 2

- Part 1: The Crow Creator James O’Barr’s Early Years

- Part 2: The Crow and the Caliber years

- Part 3: After The Crow: The Works of James O’Barr

James O’Barr has published around 416 pages of sequential art in his life, not counting things he wrote but didn’t draw. By my count, Caliber published 182 of those pages in 1989, most of which he penciled, inked, and lettered at night while working a day job at an auto body shop.

James O’Barr joined Caliber Comics during its earliest days. The company was founded by the late Gary Reed, who owned a chain of book stores and comic shops in the Detroit area, and emerged from the ashes of another Michigan publisher, Arrow Comics. Arrow, founded by Stuart Kerr and the late Ralph Griffith in 1984, published Kerr and Vincent Locke’s zombie series Deadworld and Griffith and Guy Davis’s fantasy series The Realm all of which were at least modestly successful, but not enough so to keep Arrow afloat after the black and white comics implosion.

“I’m not exactly sure how it finally came together but I found myself telling Vince and Guy that I would publish the books,” Reed wrote in his history of Caliber Comics. “Not only that, I would start up a whole publishing company.”

Reed brought aboard a few other Arrow refugees, including Mark Bloodworth’s Night Streets, but he didn’t want his new venture to be a mere reincarnation of someone else’s company. He set about recruiting additional talent and titles to distinguish Caliber Comics. O’Barr was one of them. Reed wrote that he was already selling t-shirts designed by O’Barr, many of them bootleg Batman shirts. In Reed’s telling, O’Barr heard he was starting a company and wanted in. O’Barr showed Reed about 14 pages from The Crow in late summer of 1988. “I thought The Crow was a bit rough in spots but I liked the sensibility of it,” Reed wrote. “I mean, anyone who can bring in quotes from the like of Antonin Artuad (‘morphine for a wooden leg’) as well as music and literature… that shapes up to be a cool project.”

O’Barr’s version of how he got involved differs. O’Barr has said that Reed approached him about joining the company, so he showed him The Crow. “[Reed] did not get it at all,” O’Barr told the Panel Borders podcast in 2014. “‘It’s just depressing James. Why would anyone want to read this?’” But, according to O’Barr, Reed ended up needing to publish an additional title to get a better deal with the company’s printer.

It’s clear that O’Barr and Reed came to have their differences, but it wasn’t always so. “We were both from Detroit…we drank, we were both smokers, late night coffee drinkers, etc.,” Reed wrote. “Jim and I got along pretty well in the early days.”

O’Barr quickly became a prolific contributor to the company. “Jim was a great addition to the beginning of Caliber,” Reed wrote. “He seemed to be excited about being a part of an artist community.”

O’Barr painted a cover for Deadworld # 10 the first comic published under the Caliber banner, did finishing art over Vincent Locke’s breakdowns for the issue. His Deadworld work was credited as “Jonny Zero,” but he’s identified as “Jim O’Barr” in the inside front cover announcing that he would take over as regular inker for the series. The Crow appeared on the back cover. In addition to providing an eight page preview of The Crow for the first issue of Caliber’s anthology Caliber Presents, O’Barr also wrote and drew a 12 page space marines story called “IO,” featuring the first appearance of Blixa Danzig. “IO” was credited to “Barb Wire Halo Studios.” According to John Bergin, who published a color version of the Caliber Presents stories, Barb Wire Halo Studios was O’Barr, Davis, and Locke. Caliber advertised an IO graphic novel that was never completed or published, though both O’Barr and Bergin would use the character Blixa Danzig in later projects detailed in the next part of this series.

In other words, he was initially committed to writing, drawing, and lettering The Crow, inking/finishing the Deadworld ongoing series, and writing and drawing IO. This tendency to tackle many projects at once, most of which end up going unfinished and unreleased, would continue throughout his career.

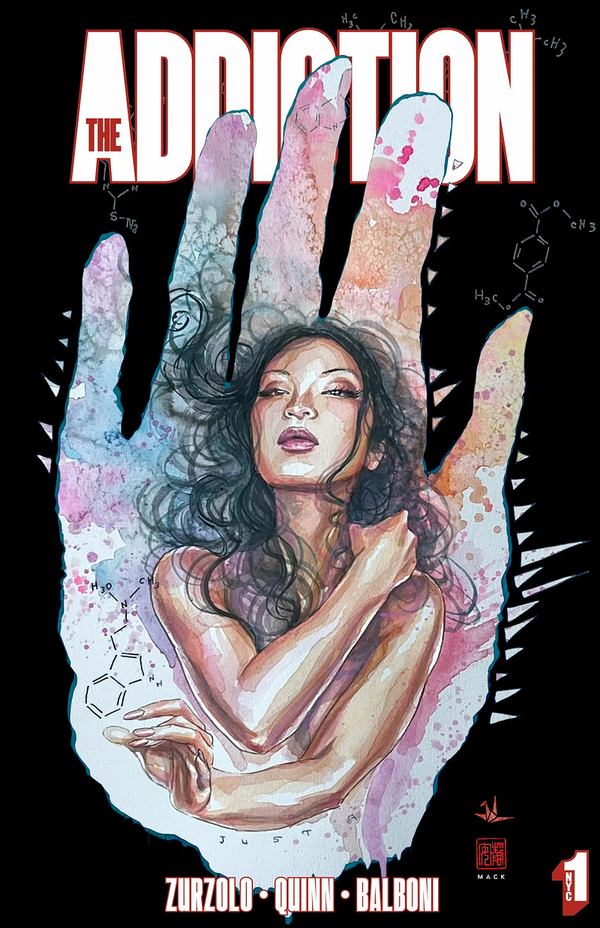

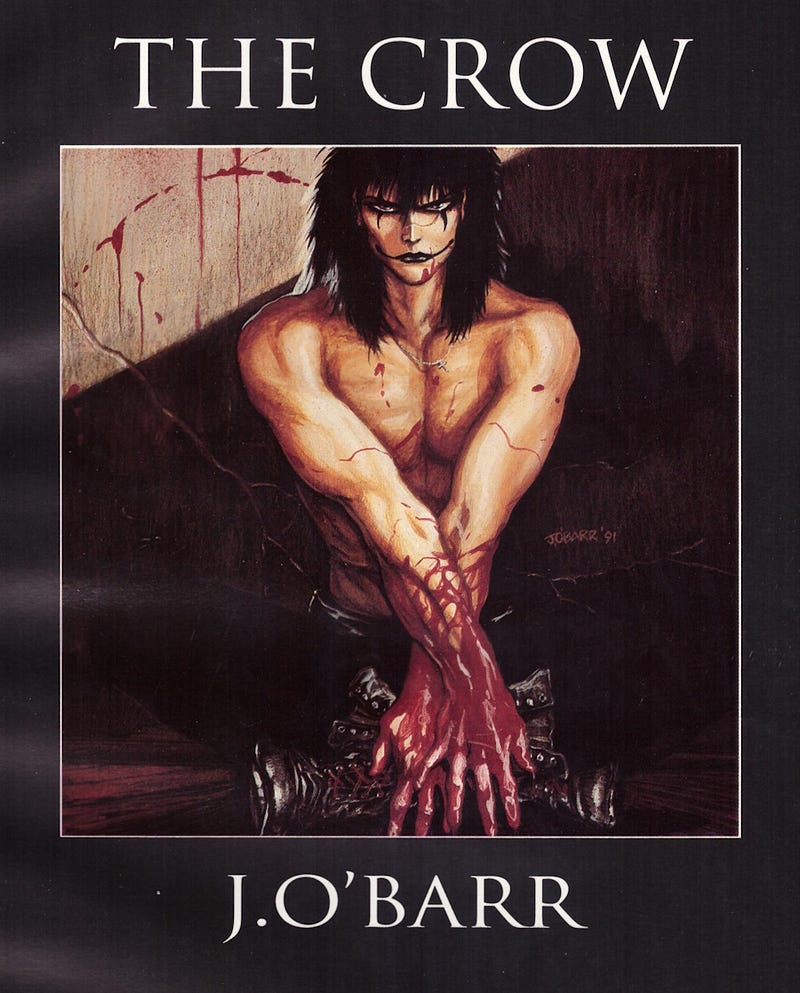

The Crow Lands

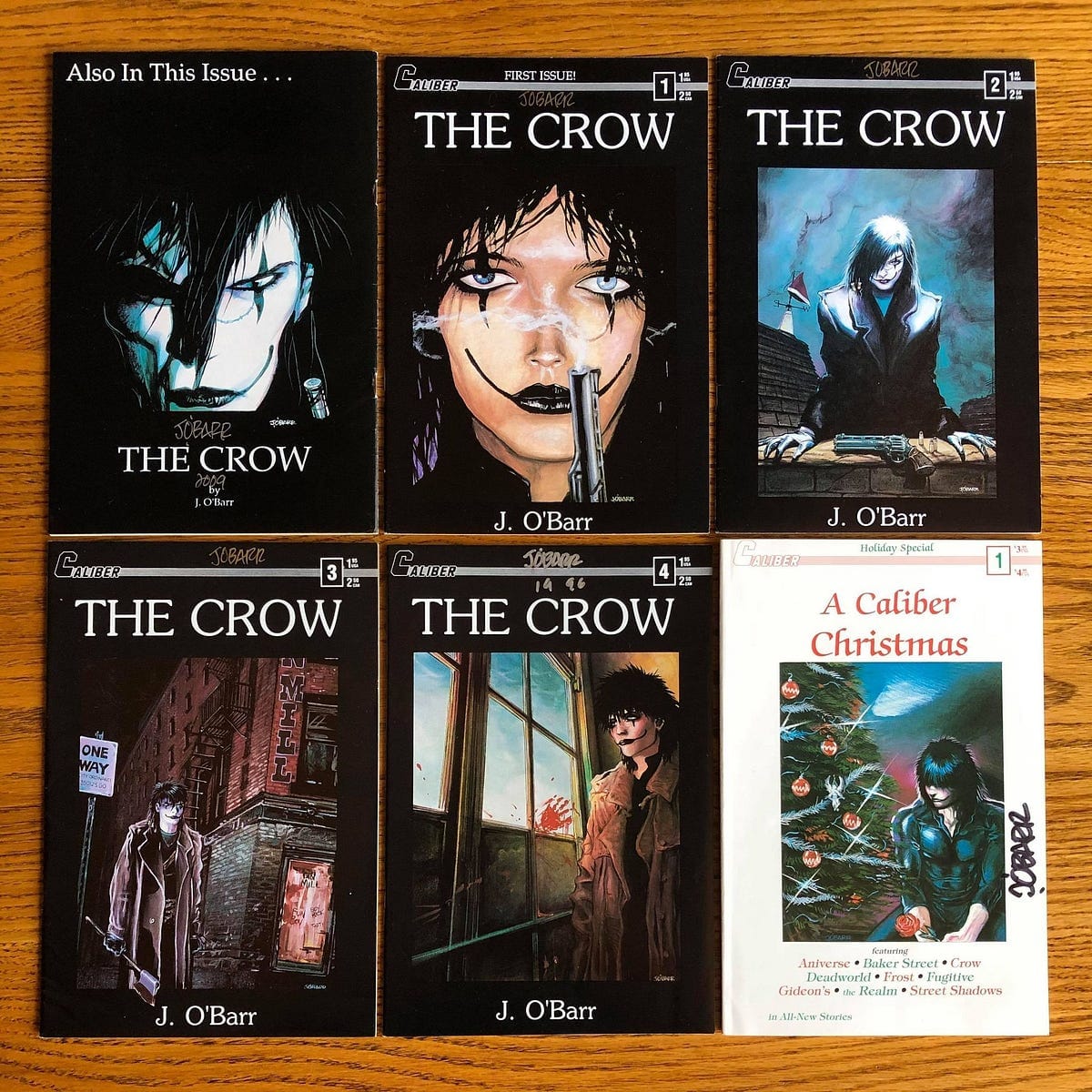

The world got their first look at The Crow in Caliber Rounds, a promotional publication Caliber released likely around September of 1988.

The premise of The Crow is now part of our the pop culture collective consciousness, but it was strange and confusing when it first appeared. A review of Caliber Presents in the dark fantasy/horror magazine Midnight Graffiti in 1989 described the first Crow segment as “a weird interlude in which a bizarre character who looks like a vampire street-mime encounters a burly burglar and proceeds to terrorize the man,” and concluded that it was “a damned effective story both because of the art and because it’s truly weird.” In a review of The Crow # 1 in Amazing Comics # 167 in June 1989, David Pattle wrote: “The Crow looks like the Joker as played by Michael Jackson… and before anyone busts out laughing, let me assure you it’s far more effective-looking than it sounds.”

“People have to remember that The Crow was completely unknown at the time,” Reed wrote. “On the first orders of the first six titles, The Crow was actually the worst selling. Deadworld sold about 11,000 copies, Moontrap around 8,500, Baker Street was about 7,500, Caliber Presents and Realm both did around 6,600. The Crow had initial orders under 4,000 but because it ran late, more orders came in before printing which bumped it up to t 5,300 copies.”

But once it hit stands, The Crow # 1 quickly sold through its print run of 10,000 copies. Peattle prophetically compared it to Elfquest, Cerebus, and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. “Every year, one new black-and-white title comes along that beats the odds and becomes a monster hit after starting fairly small,” he wrote in his Amazing Heroes review. “I feel safe in predicting that for 1989 The Crow will be that up-and-comer.” The series quickly sold through print runs and became a cult sensation.

Today the book is often received more harshly. Reviews of the 2011 Special Edition note the thin plot and lack of characterization. As much as I love The Crow, I have to admit they’re not wrong. Eric proves unstoppable in his mission. He faces no setbacks. No one poses a threat. His struggle is internal: his flashbacks, his self mutilation. But it only serves to drive him forward. There’s not much characterization. We learn little about Eric and Shelly, little about Sherri, little about Officer Albrecht, and less about the killers, apart from Fun Boy being surprisingly familiar with Milton.

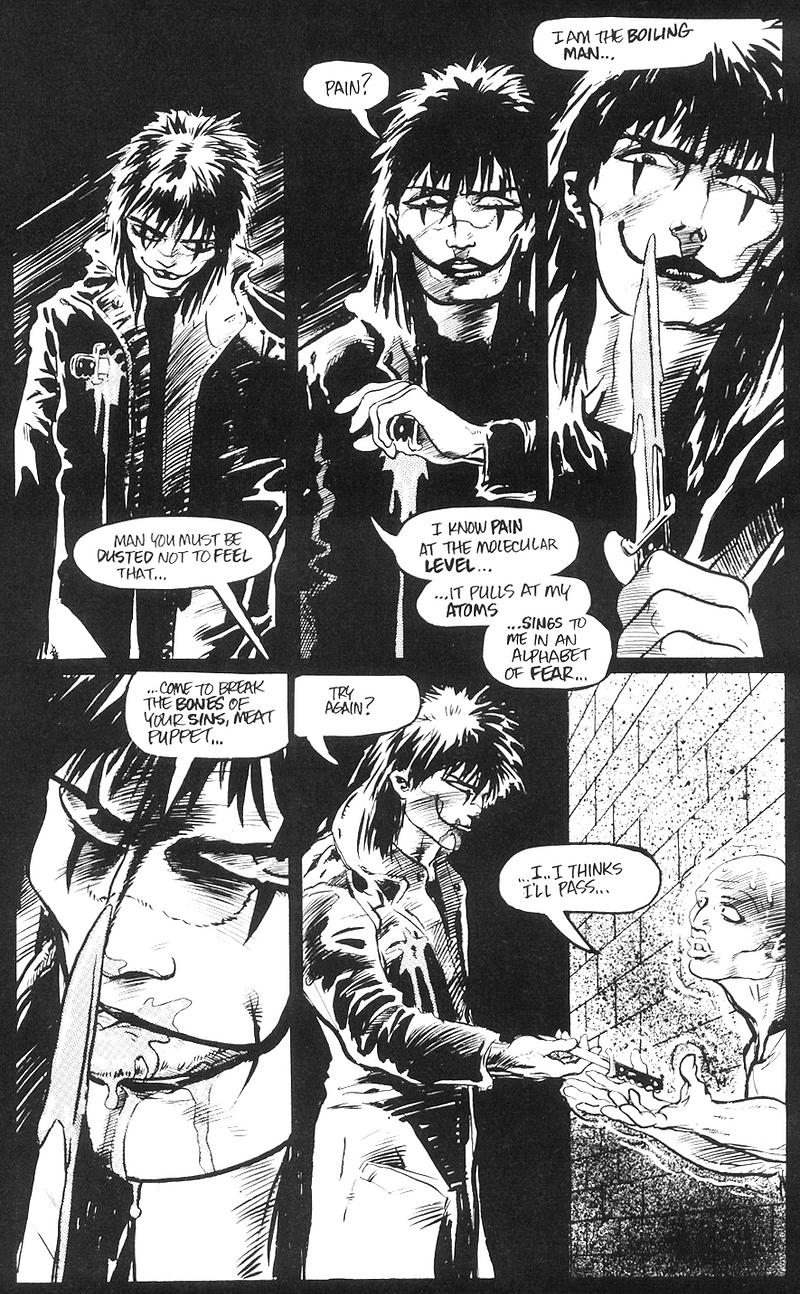

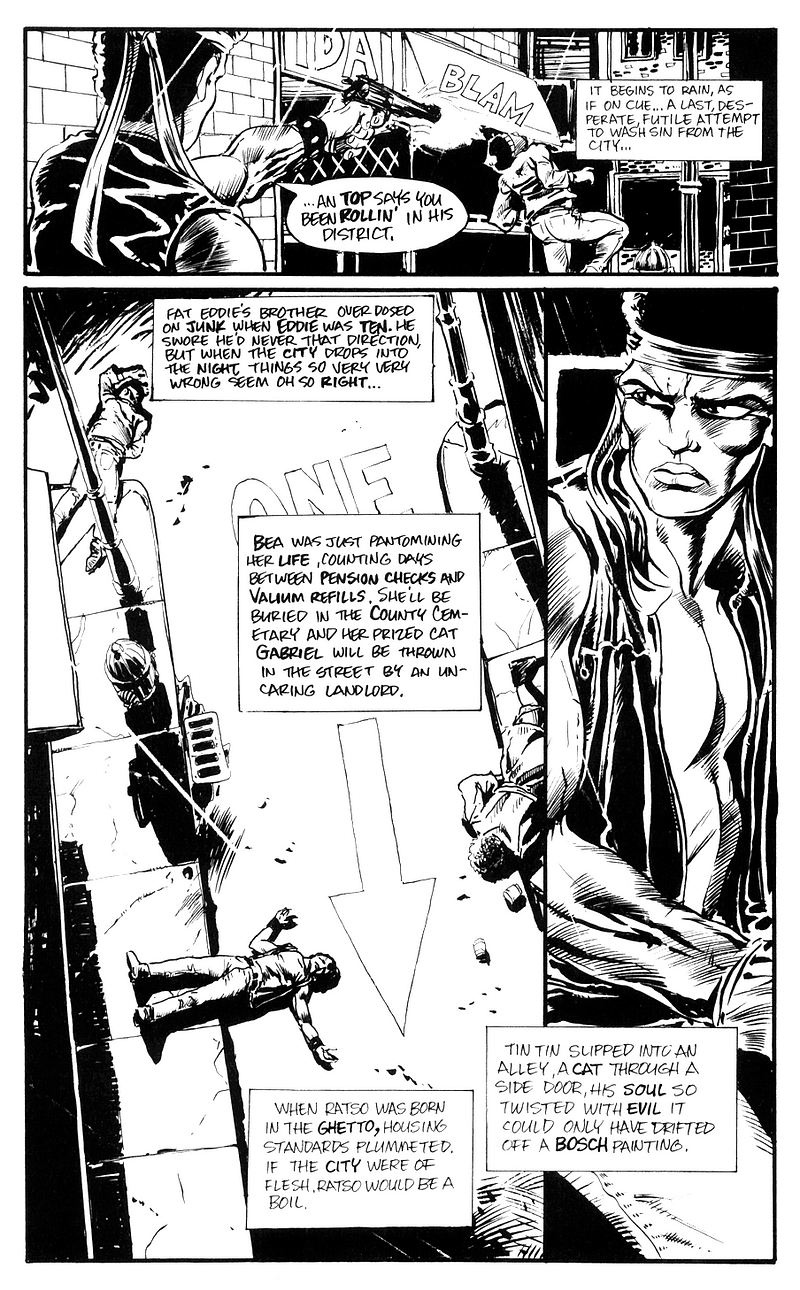

O’Barr had initially tried to bring an additional dimension to the work through a series of captions in The Crow “Part One: White Heat” that read like a combination of Will Eisner and Jim Carroll:

Fat Eddie’s brother over dosed on junk when Eddie was ten. We swore he’d never that direction [sic], but when the city drops into the night, things so very very wrong seem oh so right.

Bea was just pantomiming her life, counting days between pension checks and Valium refills. She’ll be buried in the county cemetery and her prized cat Gabriel will be thrown in the street by an uncaring landlord.

When Ratso was born in the ghetto, housing standards plummeted. If the city were of flesh, Ratso would be a boil.

This narration stops abruptly in “Part Two: New Dawn Fades.”

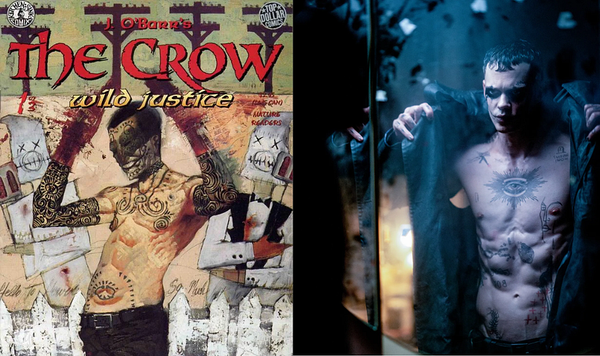

O’Barr said during a during an interview at the DiNK Denver 2018 convention that he wanted to expand on the characters in new a film adaptation of The Crow. “In real life no one thinks they’re a villain,” “I don’t want them to just be like cliched standout bad guys, they all have stories and relationships. Unfortunately, O’Barr reportedly had no input in the forthcoming Rupert Sanders directed The Crow film, so we may never see what he had planned.

What kept The Crow from being yet another violent vigilante comic was its emotional content. It was rare to see such raw emotion on the pages of comics back then. Confessional comics from the Underground Comix scene come the closest, such as Art Spiegelman’s “Prisoner on Hell Planet” and O’Barr mentor Vaughn Bode’s Schizophrenia.

Other Caliber

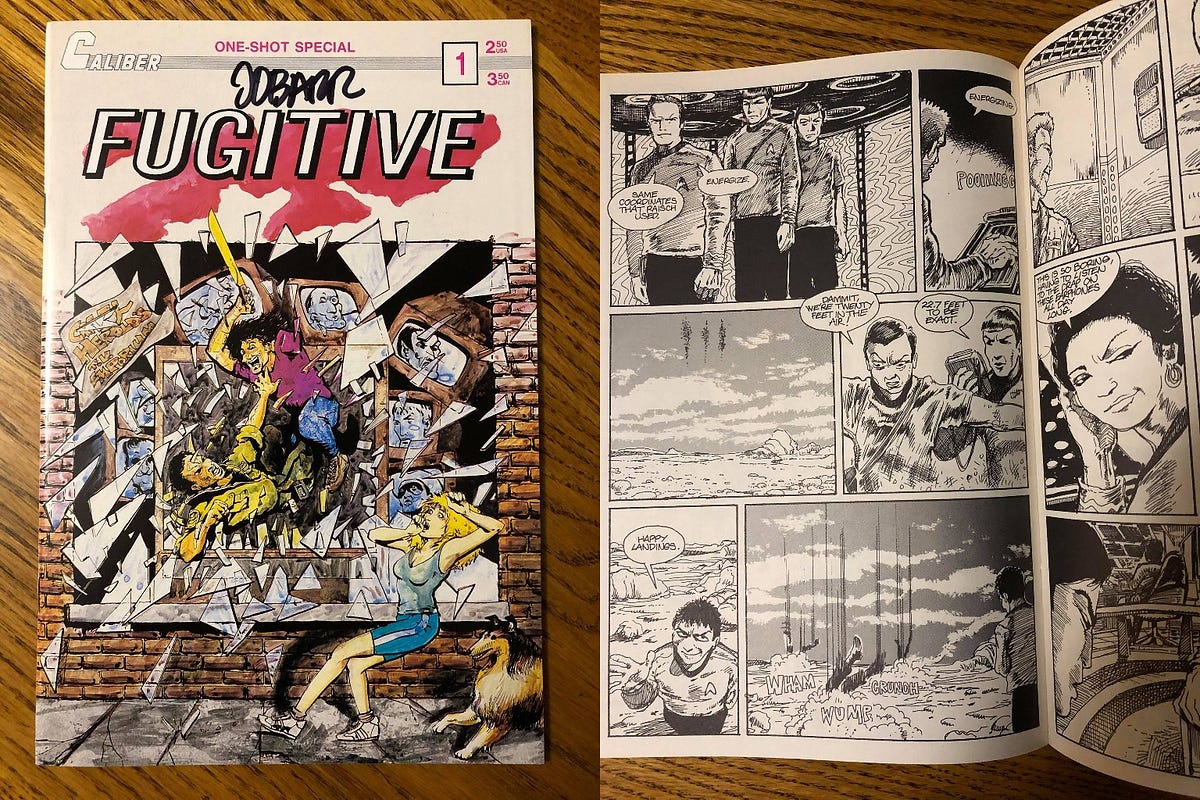

O’Barr’s stint as Deadworld inker lasted only one issue, but he did paint several covers for the series. Only two installments of “IO” were ever published in Caliber Presents. The graphic novel never materialized. But he did find time for a few other projects. In Caliber Presents # 2 he penciled the first installment of a comic called “Gideon’s.” a short horror story written by Reed under the pen name Kyle Garrett about a pawn shop owner. Crow fans will of course recognize the name “Gideon,” but it’s an entirely different character. O’Barr also drew a 13 page Star Trek parody in a one-shot comic called The Fugitive.

O’Barr also did his first collaborations with John Bergin during this period. “James and I started writing to each other at about the same time,” Bergin told Under the Volcano. “Our first letters to each other crossed each other in the mail — and they both said the same thing ‘brother, is that you?’”

“Neil Gaiman said that John and I were like the twin doctors in Dead Ringers, because it looked like we were having conversations without saying a word to each other,” O’Barr told Comics Scene in 1992.

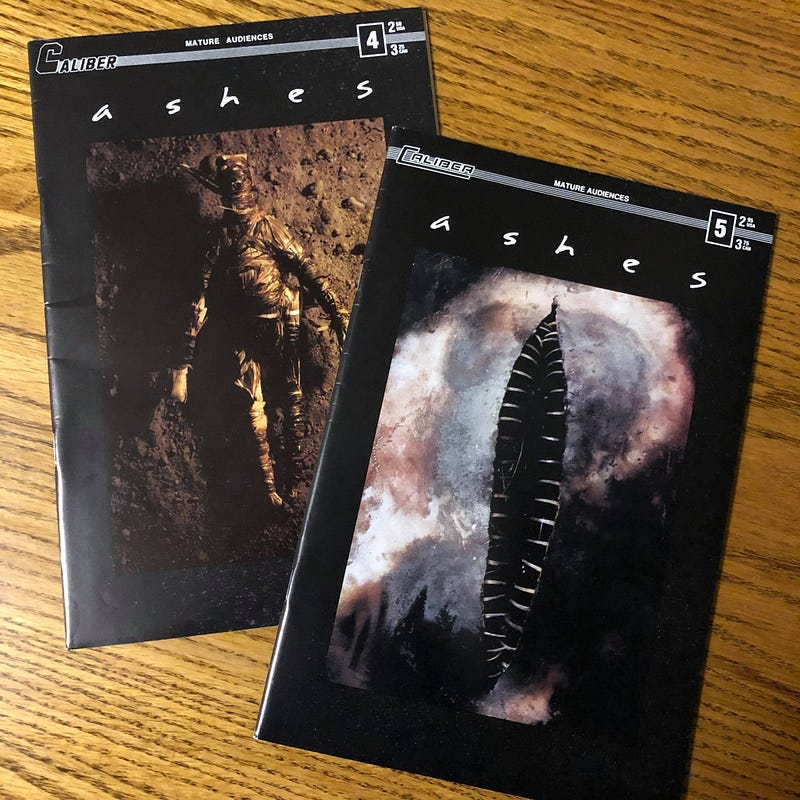

Bergin’s anthology Ashes #4 featured two collaboration with O’Barr: “Angelman” and “Wasp Baby.” A third, “Coyote,” appeared in Ashes # 5. These appear to be drawn by Bergin based on descriptions of dreams provided by O’Barr. A similar collaboration “German Film, Blurred,” appeared in Bone Saw in 1992 and was reprinted in Bergin’s Dust collection.

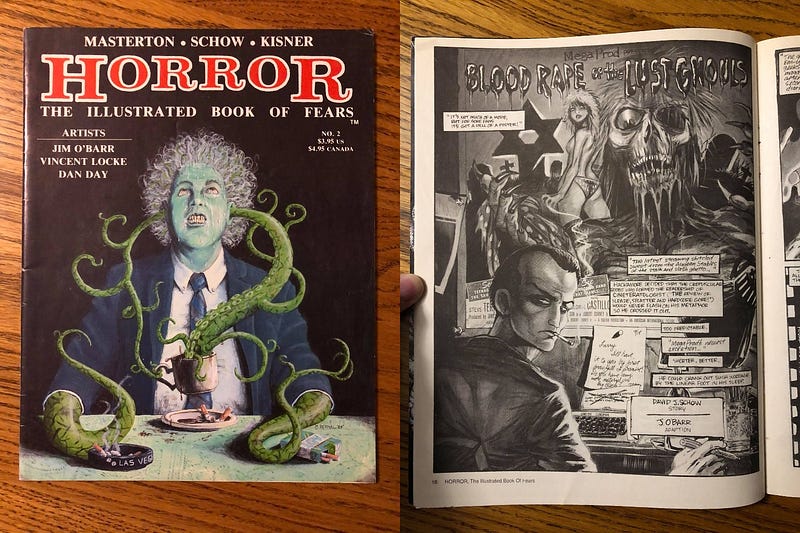

Almost all of O’Barr’s work from this time period was for Caliber, but he adapted future The Crow screenwriter David J. Schow’s short story “Blood Rape of the Lust Ghouls” in Horror: The Illustrated Book of Fears #2 from North Star, a publisher best known for publishing Faust: Love of the Damned. I’m not sure whether this was before or after he decided to leave Caliber. He also did a four page story set in his and Bergin’s “Gothik” universe, discussed in the next segment of this series, called “Frame 137,” which was published in Storming the Reality Studio in 1991.

Check out John Ekleberry’s James O’Barr Collector website for more of O’Barr’s Caliber-era work.

From Caliber to Tundra

O’Barr’s break with Caliber appears to have been motivated primarily by money. O’Barr told Panel Borders that he had told Reed that he should pay Guy Davis and Vincent Locke first since they were dependent on the money they made from comics while O’Barr had a day job and that Reed ended up not paying O’Barr at all. He made a similar claim in an interview at Hamilton Comic Con 2017.

Reed wrote that “O’Barr went to Tundra where everyone was going because of the high page rates.”

It’s not hard to imagine why he would jump ship regardless of the payment situation at Caliber. Tundra was founded by Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles co-creator Kevin Eastman after he and the other co-creator, Peter Laird, decided to stop publishing creator-owned material from other creators through their company Mirage Studios. Eastman quickly became famous for his generous advances. The Comics Journal reported that it was not unheard of for artists to take Eastman’s money and then never deliver any work.

O’Barr, fortunately, was not among the artists who took Eastman’s money and ran. The conclusion of The Crow was published in 1992.

Crossing Over

What really makes The Crow historically important is its crossover appeal to people outside the usual audience for comic books, particularly the goth subculture. The book is peppered with musical references, from the opening dedication to Ian Curtis to song references in chapter titles to lyrics appearing in dialog.

O’Barr has said the comic had a disproportionately high number of female readers for a comic book of the time. I can at least anecdotally confirm that it was one of the few comics in the 1990s that I knew of that had any female readers, though it’s long since been eclipsed in that regard.

It clearly had some cachet outside of the comics world. Trent Reznor, a known comic book fan, told Kerrang! in 1994 that he did The Crow film soundtrack because he knew O’Barr, and an interviewer for Maximum Rock ‘n Roll asked the band Sludeworth in 1990 how they got “such a famous celebrity as Jim O’Barr” to draw the cover their 7". Oddly enough, however, his album cover art has remained mostly with obscure groups, remaining further underground than, say, his fellow Caliber artist Vincent Locke, who drew many Cannibal Corpse album covers.

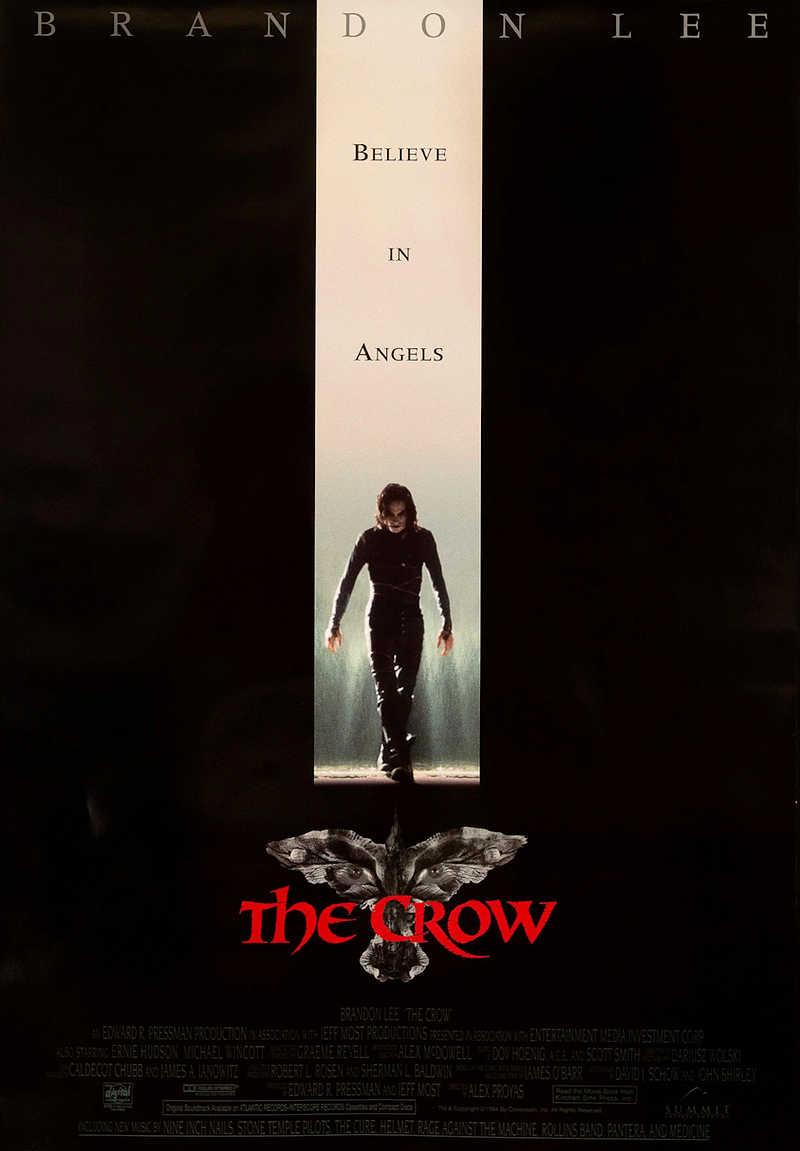

The release of The Crow in early 1989 was perfect timing for a breakthrough to mainstream culture. The Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles franchise was only becoming more popular ahead of the release of the 1990 live action movie, and Hollywood was scouring indie comics in search of the next big thing. Men in Black, Rocketeer, Tank Girl, and Judge Dredd all found their way onto the big screen over the course of the next decade. Meanwhile, anticipation was growing for Tim Burton’s Batman movie. The Crow was an indie comics hit that Hollywood big wigs must’ve thought could be the next Batman.

The Crow’s journey to film began with producer Jeff Most and writer John Shirley. The two had already worked on an adaptation of Shirley’s novel The Specialist. Most told Colin J McCracken that they were seeking an artist to illustrate a cyberpunk novel named Black Glass (incidentally, O’Barr would briefly call his cyberpunk comic project Black Glass before settling on Gothik. For more on that see the next part of this series.) Most recalled that Shirley got a referral to O’Barr through the Detroit Free Press. Shirley, on the other hand, recalled that he had pitched a comic book called Angry Angel, only to have it rejected because it was too similar to The Crow, which he was unfamiliar with. Shirley says he picked up a couple issues of The Crow and thought “This should be a movie.” Shirley and Most approached O’Barr and began shopping the project around Hollywood.

Most told McCracken that O’Barr received offer from New Line Cinema to completely buy-out The Crow, but they told him it would have to be a PG-13 movie. O’Barr rejected the offer and stuck with Most and Shirley. The team eventually made the film with Edward Pressman.

The film, released in 1994, brought O’Barr, The Crow, and Outlaw Comics, to a whole new audience. The soundtrack, as the AV Club put it, “resurrected grunge kids as goths.” As I’ve written before, The Crow introduced me a different world and told me I could be a part of it.

And that’s the greatest legacy of The Crow: It helped so many of us find ourselves and each other.