Outlaw Comics Prehistory Part 1: EC’s “New Trend”

A prehistory of Outlaw Comics could stretch back as far as the Marquis de Sade’s The 120 Days of Sodom in 1785, or even to paleolithic…

A prehistory of Outlaw Comics could stretch back as far as the Marquis de Sade’s The 120 Days of Sodom in 1785, or even to paleolithic erotic art. It could cover films, novels, art, music, and more. But let’s stick to comics. We’ll begin with Entertaining Comics, better known as EC, because you can draw a straight line from those books to Outlaw Comics.

The story of the rise and fall of EC, the comic book panic of the 1940s and 50s, the publication of Seduction of the Innocent, and EC publisher William Gaines’s disastrous Senate testimony are some of the comics medium’s most well-documented history. If you want the full story, read David Hajdu’s The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic Book Scare And How It Changed America. What’s interesting to me here, and relevant to the eventual development of the Outlaw Comics tradition is the path they paved for future artists.

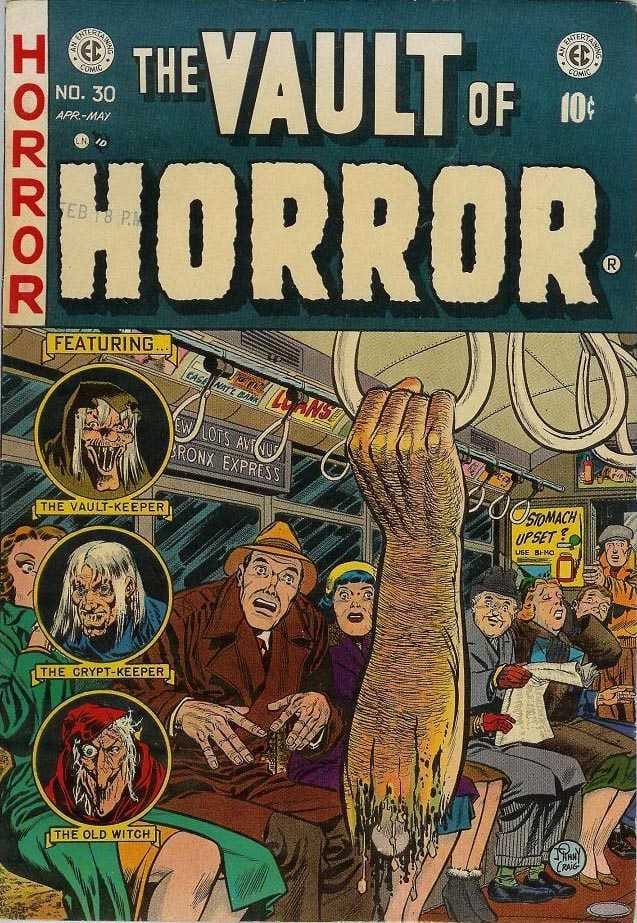

When people talk about EC, they’re usually talking about Tales from the Crypt, The Vault of Horror, and The Haunt of Fear. Though the company’s infamous “New Trend” line included many other titles as well (notably Mad and Harvey Kurtzman’s surprisingly subversive war stories in Two-Fisted Tales and Frontline Combat), I’m most concerned with those three horror/thriller comics.

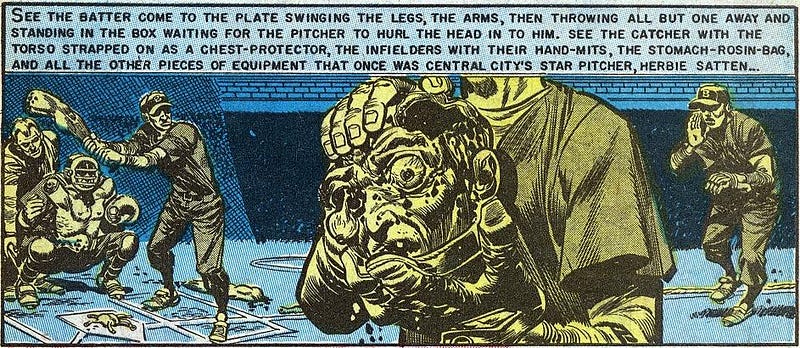

On one hand, it’s easy to see why parents of the time were so outraged by these titles. Many of the stories are gruesome even by today’s standards, including the infamous “entrails baseball” story (“Foul Play” from The Haunt of Fear # 19). But EC was, for the most part, following in the tradition of lurid horror and true crime prose stories of the era, often lifting concepts wholesale from previously published works.

Much of the outrage stemmed from the fact that these were comic books, a visual medium thought of as primarily for children. Reading about decapitation or cannibalism in print was one thing. Seeing it was another. And comic books were in a unique position to bring this sort of gory content to the masses.

In the early days, the difference between comic books, as a medium, and comic strips was fairly arbitrary. The earliest of what we’d today call comic books (as opposed to, for example, the “wordless novels” by Lynd Ward and others) were just reprints of newspaper strips. New Fun, the first comic book to publish original material, consisted of rejected newspaper strips.

As comic books came into their own as a medium, publishers and creators realized they could get away with things that would never fly in a mainstream daily newspaper. For most publishers, that just meant lowering the bar on quality. But with the Motion Picture Production Code still in full effect in the mid-1950s, comic books had, at least in theory, more freedom as a form of visual storytelling than film. EC wasn’t the first to publish stuff that would probably never have seen print in a newspaper — Fletcher Hanks’s nightmarishly bizarre comics come to mind here. But EC was the most notorious and managed to push the limits to a breaking point.

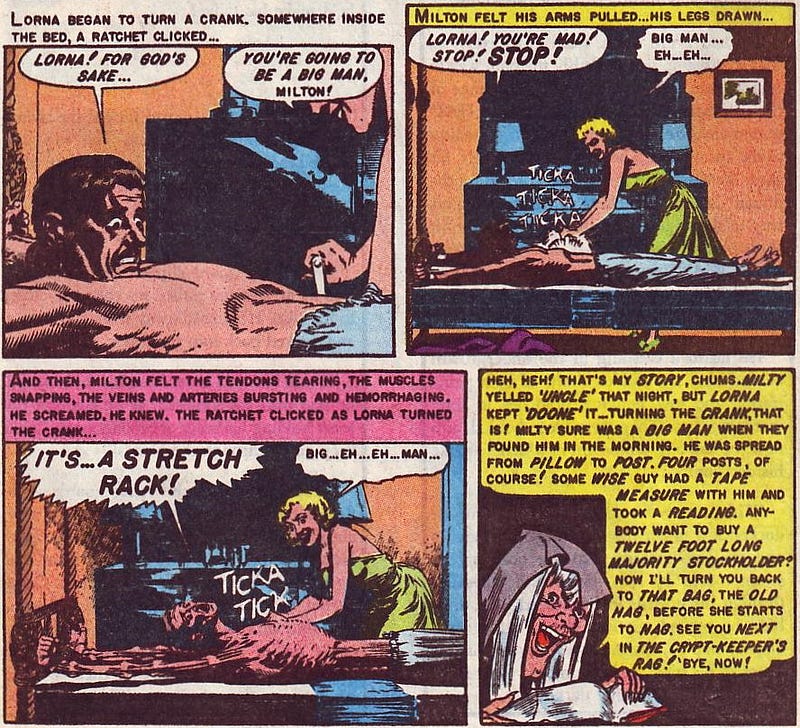

It wasn’t just gory images that made EC comics so disturbing. Sometimes it was situations or even facial expressions.

Cartoonist Kayfabe co-host Ed Piskor recalled in a recent interview that a story in Haunt of Fear # 18 (“Bed Time Gory”), reprinted by Gladstone Comics in the early 1990s, was the first comic that truly disturbed him. It involves wife torturing her manipulative husband on a stretch rack. “Her pupils are pinholed, she’s got this maniacal look on her face,” Piskor said. “To this day I still think about that [story], it really hit me hard.” It’s noteworthy that the woman’s pinholed pupils came to mind more readily for Piskor than the grotesquely stretched man.

What’s left to the imagination is sometimes the most disturbing. For example, “Split Personality,” from Vault of Horror # 30, ends with twin sisters literally splitting a man in half. The story closes with the women laying in bed with their halves of the cleaved corpse. Even without the implied necrophilia, the idea of the women sleeping beside a mutilated corpse is troubling on its own.

It’s easy enough to imagine “Split Personality” appearing in a more explicit form in Cry for Dawn or Verotika. But I’m not sure a more explicit version would be more effective, more haunting. The ability of stories like “Bed Time Gory” and “Split Personality” to disturb and provoke decades later speaks to the storytelling chops of the EC stable.

As Hajdu notes, romance comics were probably the most subversive comics of that time period, particularly those by Dana Dutch. But there was more going on in EC’s comics than mere shock. A common theme in EC’s horror stories that the post-war suburban lifestyle wasn’t all it was cracked up to be, that lurking beneath Leave to Beaver-esque surface of domestic bliss was nightmarish violence and deep discontent with marriage, family, and conformity. Though cliche today, those themes would provide fertile ground for creators for decades to come. Meanwhile, Kurtzman's war comics dished out a healthy skepticism of war and American imperialism in lieu of the jingoism one might have expected at the time. Later, EC would do more explicitly socially conscience stories (most notably “Master Race”) in the title Impact, but there’s an interesting, more subtle thread running through these earlier titles.

EC helped establish comic books as a, perhaps THE, visual mass medium where creators could explore ideas and content that they couldn’t pursue elsewhere. The establishment of the Comics Code Authority, largely in response to EC, set this freedom back by decades, but EC continues to inspire creators to push boundaries in their work even today.

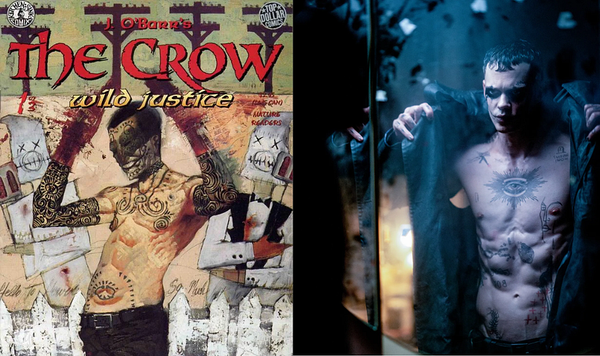

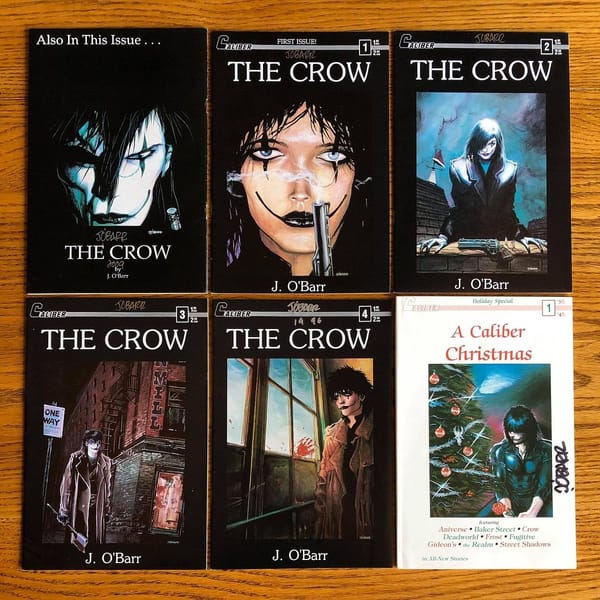

The creators of the “big three” of the first wave of Outlaw Comics — Faust The Crow, and Cry for Dawn — were born after EC stopped publishing its horror books. But they grew up on comics that were directly influenced by EC.

“I never really read superhero books, it was more horror books and things like that,” The Crow creator James O’Barr said in an interview with R. Alan Brooks in 2018. “EC comics were a little before my time, though I got into them later. It was more the Warren books, Creepy and Eerie. And the stuff Marvel was putting out like Where Monsters Dwell.”

But EC inspired a whole new generation of writers and artists. Stephen King was a huge fan. But more interesting for us was a new generation of comics creators who went on to directly influence the emergence of Outlaw Comics: the Underground Comix movement. More on that next time.