Outlaw Comics Prehistory: The Problematic Legacy of S. Clay Wilson

EC only published horror comics from around 1950 until 1955. But that was long enough to warp a new generation of cartoonists. A decade…

EC only published horror comics from around 1950 until 1955. But that was long enough to warp a new generation of cartoonists. A decade after the Comics Code Authority defanged newsstand comic books, Underground Comix .

“I always saw the underground comix movement as a sort of extension of the ECs,” S. Clay Wilson told World of Fandom in 1998. “In my estimation, we were taking it one step further by adding sex and drugs and carnage and stuff. Hence the name underground because they kept them under the counter, or else they were getting busted.”

The Underground Comix movement emerged in the early-to-mid sixties out of college newspapers, humor magazines, underground newspapers, and the poster art scene among other places. But it was Wilson who injected EC’s morbidity into the Underground scene. And while many EC stories remain unsettling today, they aren’t particularly shocking given modern media’s high tolerance for violence and gore. Wilson’s work, on the other hand, stands shoulder to shoulder with the most graphic media of today. He was visual media’s Marquis de Sade — a straight, American version of Tom of Finland.

Wilson dove into the Underground scene with the aptly named “Head First” in Zap # 2, where a pirate chops the head of another pirate’s giant dick and eats it. It’s hard to imagine what seeing “Head First” would have been like in 1968. It remains one of Wilson’s most famous/infamous pieces today, along with “Bullet in the Bunghole” from Zap # 4. “Bunghole” was overshadowed by Crumb’s incestuous “Joe Blow,” but the strip forshadowed the sexual violence that Wilson, Crumb, and others would churn out over the following decade.

These strips are often credited/blamed for pushing Robert Crumb and the rest of the men of the Underground movement towards increasingly violent material. “[Wilson] was into drawing anything he felt like and pushing all those thing as far as he could,” Crumb said in an interview in Heavy Metal in 1983. “I had always had this kind of built-in censor in my head because I was always trying to do something that had popular appeal, you know? And this censorship was so deeply ingrained in me that I never even thought of it. It was just there.”

There was a dark side to much of Crumb’s work well before he met Wilson. “Fritz Comes on Strong” from Help! # 22 (1965) depicts what appears to be a sexual assault, and in “Fred, the Teen-Age Girl Pigeon” from Help! # 24, Fritz apparently eats an anthropomorphic teenager. But it’s true that Crumb and his peers took a much darker turn after Wilson joined the Zap crew.

Wilson is often cited as a forerunner to Outlaw Comics, and with good reason. Although the Outlaw Comics generation cites other Underground creators like Richard Corben as key influences — more on those influences in future articles — it’s clear that Wilson set the stage for what Outlaw Comics creators would do later. The buckets of blood and gratuitous torture scenes of the Outlaw Comics movement were all prefigured by Wilson. “My idea is not to entertain ’em but to enlighten ’em. Or to make ’em sick. One or the other,” Wilson told Bob Levin in a Comics Journal interview in 1995. “Sometimes it happens simultaneously.” That famous quote could sum-up much of the Outlaw Comics movement as well.

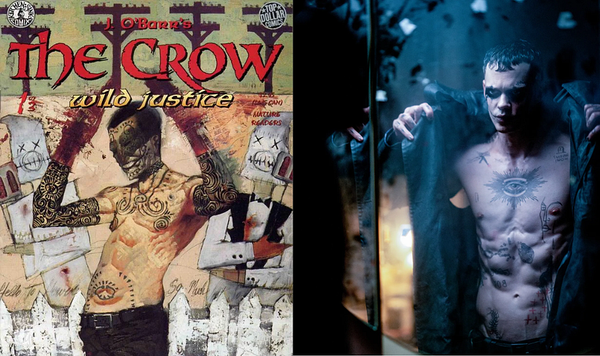

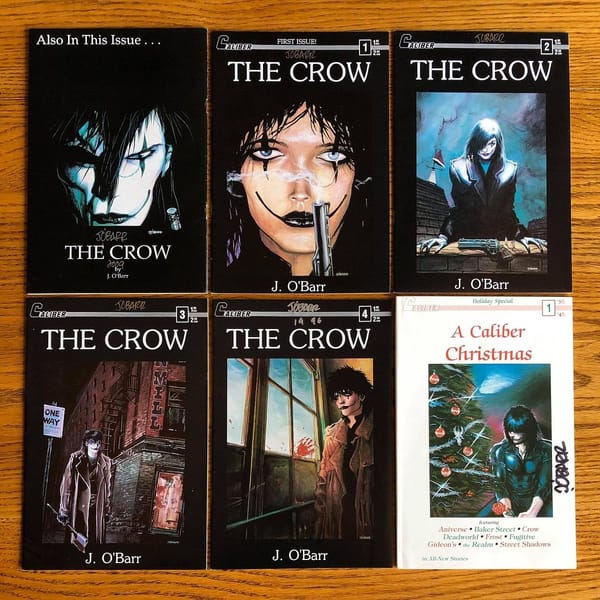

But there are some clear differences between what Wilson did and what the Brothers Vigil, James O’Barr, and Joseph Michael Linsner would do later. Not only is Wilson’s art style more cartoony than the Outlaw Comics vanguard, his stories are equally cartoony.

“He exaggerates and mocks more than he analytically, precisely renders,” Levin wrote. “He triggers less pain as a result. Because he makes little effort to humanize his characters, readers do not identify with them. Because he does not structure stories, readers are not manipulated into an emotional involvement. Less hook-laden drama powers his images, so consciousnesses are less apt to be seared by them than by the ECs he admired.”

None of which is to say Wilson’s work doesn’t hit home. As Levin writes: “Even casual exposure to Wilson will not leave one unaffected.”

Reassessment

There’s been a much needed reassessment of Robert Crumb’s role in the canon of modern comics in recent years, thanks in large part t a passing remark by Ben Passmore at SPX in 2018. Heidi MacDonald wrote:

I see Crumb’s work as an artifact of what the indie comics scene used to be, a group of reactionary men rejecting society’s norm and confronting a sexually repressed society, creating unfiltered work because “it couldn’t be restrained or censored”. The result was self-centered, often sexist, racist and bigoted comics. As much as it rebels against societal norms, it’s also subject to some trappings of white and male supremacy. It’s inevitable to see it this way as we view it with a modern lens.

The same can be said of much of the output of Underground Comix. Wilson’s work is especially hard to defend, though, according to Levin, underground cartoonist and comics historian Trina Robbins said of Wilson: “[he is] an equal opportunity destroyer. He’s not a misogynist, but a misanthrope” and that he is “one of the sweetest people I know.” But I’m not the first to point out that doling out punishment in “equal measure” isn’t really balanced when certain groups — women and LGBTQ+ people for example — already take an unequal share of abuse in the real world.

“The overweening feeling accompanying Wilson’s work is one of deep sadness,” Etelka Lehoczky wrote for NPR. “Wilson’s devils, pirates and busty women perform compulsively, their rictus grins parodies of true pleasure. Living in the Haight in ’68, witness to all its many experiments in higher human consciousness, he already seems to be asking: ‘Is that all there is?’”

It’s a question I’ve found myself asking often as my research for this series of articles, and my own morbid fascinations, have led me to some dark corners of the media landscape over the past few years. The value of transgressive art like Wilson’s typically seen as the breaking down of barriers to creativity for future generations. “The creators of each era try to expand the boundaries of the acceptable, and the authorities try to shrink them,” Levin quotes someone identified only as “Doctor” on Wilson’s work. “Those of us in the middle benefit from any ground that’s gained. for this to occur, the work must shock: new words, new pictures, new combinations.”

Yet I often find myself wondering what all this transgression for the sake of transgression — from Underground Comix to Faust to horror movies to extreme metal — has really done for us. It’s easy to look at today’s toxic internet culture, brazenly misogynistic “torture porn” films, and the rise of hate speech and hate crimes, and wonder if all that shock value ended up doing more harm than good.

But the Underground Comics movement did have some clearly positive ramifications for the development of comics as a medium and, by extension, for art and media as a whole. The movement established that there was a real market for adult-oriented comics. The best selling Underground titles sold in the hundreds of thousands. I’ve heard that Furry Freak Brothers actually outsold Amazing Spiderman at one point. The Underground showed that you didn’t need traditional newsstand distribution to build a business: they sold their work to head shops through poster distributors. It was a premonition of the future direct market business.

Underground Comix also helped establish comics as a form of artist expression as opposed to a purely commercial enterprise. “The underground was the first time cartoonists considered themselves working for their own personal reasons, personal expression as opposed to working for a publisher, working for a comic book, working for a market,” Bill Griffith told The Comics Journal in 1993. “We had no idea who our market was, we just figured they were people like us.”

And of course Underground cartoonists like Crumb, Spain Rodriguez, Justin Greene, Jaxon, and of course Art Spiegelman pioneered the use of comics as a medium for memoir and non-fiction. “The great literary successes of the new comics movement have come, largely, in the field of biographical writing. Not accidentally, most of the more talented women comic strip artists have chosen to work in this area of the field,” Bob Callahan wrote in The New Comics Anthology in 191. Those statements remain true, and it was Underground Comix that paved the way for some of what we now consider the great works of comics — quite directly in the case of Spiegelman’s Maus.

Wilson wasn’t much into the memoir scene, but I don’t know if something like Maus could have been as raw and disturbing as it was without Wilson. Practically any North American (and perhaps European and Latin American) comic book you’ve read that would have enough to sex or violence to net a PG-13 rating if it were a movie might not have been possible without the gates opened by Wilson.

Of course, if we talk about gates opened we should talk about gates shuttered as well. Wilson, Crumb, and their compatriots didn’t stop women like Robbins, Lyn Chevely, Joyce Sutton, May Wing, and Joyce Farmer from founding their own Underground Comix anthologies that were often even more transgressive — and in a more clearly positive way — than the books their male peers published. But it’s hard not to wonder how comics might’ve evolved in the scene had been more friendly to women and more women had been welcomed into the male-dominated titles. Likewise, I have to wonder what comics would have been like had the Underground movement been less white. What artists, of any gender identity or ethnicity, opened copies of Zap or Snatch or Skull only to say “nope, guess comics isn’t for me,” never to return?

We can’t know how the past might’ve played out differently. This is the history we have. All we can do now is learn from what’s come before and try to do better.

Further reading

“Black and white and gray all over,” a thoughtful article from Gutter Review on how to teach and talk about Underground Comix today.