Sad Sack: The Comic Forcing Us to Think the Unthinkable

From the very beginning, comics were dangerous. In the early-1900s, magazines like The Atlantic Monthly and Ladies Home Journal ran…

From the very beginning, comics were dangerous. In the early-1900s, magazines like The Atlantic Monthly and Ladies Home Journal ran articles accusing comic strips, still a new addition to newspapers, of undermining literacy and encouraged children to disrespect their parents and the law. In the 1950s, crime and horror comics incited a full-blown moral panic as parents and church groups hosted comic book burnings, scant years after the defeat of the Nazis during World War II. Underground comix of the 1960s and 70s struggled with obscenity laws. In the early 90s, Mike Diana became the first and only US artist jailed for obscenity.

But comics haven’t felt so dangerous over the past couple decades. There are probably a variety of reasons for that. For one, after decades of newspaper headlines proclaiming that “comics aren’t just for kids anymore,” the public might finally be starting to believe it. For another, not a whole lot feels particularly dangerous in a world where Quentin Tarantino’s pseudo-snuff torture films routinely garner Oscar nominations and you can watch Devilman: Crybaby on Netflix. What boundaries were there left for visual media to cross?

More than I’d thought, it turns out. Sad Sack is a digital comic series by artists Barbatus and Meanboss consisting of five issues, totaling more than 1,000 pages. Each issue includes a long list of content warnings. Issue three, for example, warns of:

- Explicit sexual content

- Sexual assault

- Transphobic sentiments

- Substance use

- Administration of rohypnol

- Discussion of date-rape aftermath

- Graphic violence & murder

- Body horror

- Salirophilia/mysophilia

- Decomposing human bodies

These warnings are no joke. The series includes a lot of explicit images of torture and rape. It’s heavy stuff. I won’t describe these scenes in detail in this piece, but I will continue to discuss the contents of the series in the abstract. You’ve been warned.

The series follows a group of five friends who torture, kill, and rape a series of victims, including a neo-nazi, a child molester, and a rapist. Barbatus and Meanboss describe the story as an exploration of the characters’ justifications of their actions.

“The nazi is the easiest to kill and not feel bad about it,” Meanboss says. “The other victims get more and more difficult to justify. We’re taking the readers on a journey with us. They might conclude ‘Maybe there’s never a justification for this.’ Or maybe there is. We leave it open for interpretation.”

Sad Sack has fantastic art and a cast of surprisingly likable characters, considering the acts they commit. But the series’s violence and gruesomeness go so far beyond what you typically see in media that it’s hard to recommend to most people. But I think it’s an important work, one worth thinking about.

This may surprise Sewer Mutant readers, but I’m no gorehound. I’m particularly averse to depictions of rape and torture. It’s not that I don’t think those should happen in fiction, I just think they’re usually best left off-screen. But Sad Sack works for me for some reason, despite how explicit it is.

Part of it may be that is the effort to explore the motivations of the characters and the implications of what they do. “The true horror of it all in the genre, for me, is that every character these things happen to is supposed to represent a Whole Person,” Barbatus says. “Like, a whole individual with likes, dislikes, good qualities, and shitty habits — and now imagine the concept of a whole person going through an ordeal like any of the nameless victims in Saw or Hostel. It just cranks it up to nauseating. I think a lot about Geordie the first victim’s mother for instance and just the ripple effect his death had on people who loved him in spite of him being a cartoon asshole.”

But Sad Sack only takes these notions so far. In an era where “is it OK to punch Nazis?” ranks as among the most is considered the most vexing of philosophical questions, Sad Sack asks those of us who have accepted that it’s not wrong to use violence against someone who wants one or more entire ethnic groups dead to ponder something more extreme. But it’s hard to imagine many readers actually siding with the book’s anti-heroes — especially by the end when we see where all of this is going. It feels more like wish-fulfillment turned thought experiment than an actual moral quandary. It could, though, give rise to some interesting questions. For example, if you think it’s OK to torture a child molestor, how are you different from people who defended the Abu Ghraib torturers? Sad Sack doesn’t ask this sort of thing, but perhaps it doesn’t need to.

I think a bigger appeal, at least for me, is that Sad Sack is as much a body horror story as anything else. Or perhaps medical horror: Barbatus has a background in health care that informs the work. The victims are forced to not only live through but stake awake for a series of bizarre mutilations. It provides an element of surreality to the work, while keeping frighteningly plausible.

“My favorite movie in this genre is Human Centipede 2, but the first laceration I had to deal with on a real-life human being who was telling me about their day to day life as we helped them was the scariest thing I’d ever witnessed,” Baratus says. “Everything pales and cranks up to a million when the realities of death and pain come into play. That was always the draw for me to the genre, to overcome my fears.”

It’s also, despite having spent nearly two years now immersed in some of the most violent, shock-centric comics of all time, one that genuinely disturbs me. It’s not that we haven’t seen mutilation and male-on-male rape in comics and film before, ad nauseam. What sets Sad Sack apart is how prolonged these scenes are. Most of its 1,000+ pages are dedicated to scenes of extreme violence.

Alan Moore has referred to film as being dragged through a comic at 24 frames per second. Sad Sack doesn’t give you the luxury of rushing through a scene or even of looking away for a few minutes while a scene plays out. You’re along for the full ride, blow by bloody blow. Sad Sack delves into our deepest fears and most despicable fantasies and has the guts to linger there, to play these scenarios out to the awful but logical conclusions.

It’s sort of an inversion of Katie Skelly’s recently published comic Maids. The book is inspired by the true story of the Papin sisters, who brutally murdered their employer. Maids takes the approach to violence that I normally prefer. You know from the beginning what they’re going to do, so it’s all about the build-up to the characters’ journey to committing their gruesome act. You only glimpse a fraction of the violence the sisters inflicted, leaving just a few images to imprint the horror of it in your mind. By focusing mostly on character, what little violence we see is elevated in contrast.

Sad Sack on the other hand starts in media res. We never learn what led the characters to take their first victims. We don’t get much of a glimpse of the characters until the very end of the first volume. This ends up accentuating the character scenes. You get less time with them, so they really stand-out.

Barbatus and Meanboss met online through a shared love of the survival horror video game Outlast from Red Barrels. “The game is ridden with nudity and suggestions of sexual violence,” Meanboss says. “A character almost loses his dick in a way that’s really graphic and terrifying. It’s not played as a joke. It really seemed to tap into a really deep fear.”

Both were posting fanart based on the game to Tumblr. “Meanboss was drawing really gruesome horror stuff that nobody else was quite doing, which drew me way in,” Barbatus says. “Meanwhile I was drawing what amounted to torture porn of a particularly misogynist dirtbag character as the victim, which has just become my brand all over. I think we both bonded over one another’s art and then nodded our heads in agreement like, ‘yeah fuck that dude.’ We noticed we were some of the only people making this sort of art and we were like ‘we’re both the same type of freak, we should be friends.’”

They started Sad Sack in 2018. Barbatus, who is Jewish, began drawing the series largely in response to the resurgence of white nationalism in the US. “I wanted to make this angry, petulant comic about killing a Nazi,” he says. “I was mad, and that was my target.” He didn’t have a grand, multi-issue story arc planned out at first. He just drew, and the characters, themes, and story grew from the work.

Barbatus shared a few rough pages with friends, with no expectation that Meanboss, or anyone else, would ink them. “I did the first couple of pages to see how they’d look,” Meanboss explains. He draws for a living, but thought it would be fun to work on a side project between commissions. “Doing comics, turns out, is way more stressful than commissions but it’s way more fulfilling,” Meanboss says. “And it makes the periods where I do other work more enjoyable too. In the end it was a chance I took because I wanted to work on a project that I was more emotionally involved in, and it was very much worth it.”

As the project unfolded, Barbatus began thinking about the characters and how they justified their actions. “I was thinking: ‘What’s wrong with these guys?’” he explains. “For me, I like to draw things that are shocking. It speaks to the id. For me, it’s fake. But for the characters, it’s real. I wanted to understand why they would do something like that.”

The pair published the series on Gumroad and Itch under the banner of “SUS.Space,” a publishing collective consisting of Barbatus, Meanboss, and a few friends doing similar working, including Gross Kelly and Haruspex. They’ve shopped the series around to a lot of publishers, but so far haven’t had any nibbles. “We got a lot of replies along the lines of ‘Get back to us if you do something with a little less ass-stabbing,’” Barbatus says.

They also tried selling print versions of the books through the print-on-demand service Lulu, but were promptly kicked off the platform. “It’s understandable, we’re pretty OK with it,” Meanboss laughs.

Their future plans sound just as relentlessly anti-commercial. Their next project is called pooppix@yahoo.com. “It’s about a guy that takes photos of his dumps for a Kik chatroom he’s a part of revolving around the topic,” Barbatus says. “The running gag in that one is that there are never any visible turds on screen. That’s turned into this fabulous game of panel and speech bubble placement to block the offending object.” Then they plan a sequel to Sad Sack titled Sortie, along with a number of shorter works.

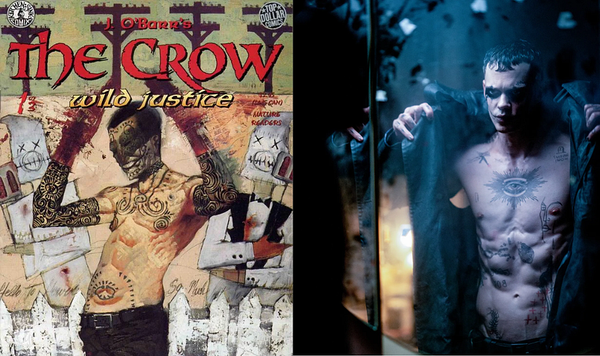

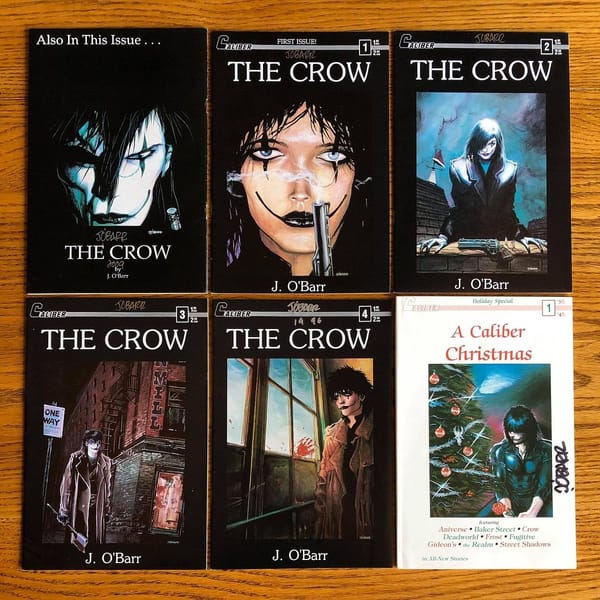

Sad Sack is the latest in a long tradition of transgressive works, from novels like 120 Days of Sodom and Last Exit to Brooklyn to comics of the underground movement and later “Outlaw Comics” like Faust: Love of the Damned.

Outlaw Comics, particularly Faust and the Boneyard Press and Verotik lines (both edited by Hart D. Fisher) pushed the boundaries of what you could do in a comic near a breaking point in the 1990s. Most of those works have remained on the margins of the industry, but they cracked open space for more mainstream works. I don’t know whether Preacher and The Boys author Garth Ennis ever even read any Outlaw Comics, but it’s difficult to imagine his work, particularly Crossed from Avatar Press, finding a home in the comics market without the trail blazed by books like Faust.

Sad Sack’s creators weren’t directly influenced by Outlaw Comics. Instead, they were inspired mostly by Japanese comics, horror films, and novels by the likes of Clive Barker and Chuck Palahniuk. But Barbatus and Meanboss seem to me to be inheritors of the Outlaw Comics tradition. Sad Sack is angry, obsessive, mixes sex and death, the creators come from outside the establishment, and the series is way outside the bounds of good taste.

Other recent-ish works have been tagged with the “Outlaw Comics” label, including Fukitor by Jason Karns and Benjamin Marra’s books like Terror Assaulter: O.M.W.O.T. But these are mostly self-conscious pastiches of old action and exploitation films. Nothing in them makes me squirm the way Sad Sack does. Nothing in them seems particularly transgressive.

Some might argue that criticism of the racist jokes and stereotypes found in Karns and Marra’s works is evidence that these books are boundary-pushing or dangerous in their own rights. But despite what Palahniuk might have you think, there’s nothing transgressive about racist humor, especially not recycled jokes from Team America. Besides, the minor controversy over Fukitor and Marra’s Lincoln Washington Free Man didn’t stop Karns and Marra from landing publishing deals with Fantagraphics, one of the most prestigious comic book publishers around, and receiving praise from a wide range of indie comics luminaries. Meanwhile, Daryl Ayo, who criticized Mara, has been harassed for years by racists. Note that I’m not implicating Karns or Mara in Ayo’s harassment, just pointing out the asymmetrical treatment. Also compare Karns and Mara’s experience with that of Barbatus and Meanboss, who have been kicked off a self-publishing platform and (thus far) ignored by the comics establishment.

What Barbatus and Meanboss, along with a few others — like Tia Roxae and MechanicalPencilGirl of Reptile House fame — show us, is that it’s still possible to push boundaries without falling back on reactionary tropes. There’s a precedence for this in the undergrounds of the 60s and 70s. Tom Veitch said the philosophy of the underground movement was “THINK THE UNTHINKABLE.” And indeed, much of that work remains edgy or beyond edgy today and, of course, paved the way for practically all future comics for adults in the US. But the most subversive comics of the underground era weren’t by Irons or R. Crumb or S. Clay Wilson. They were titles like Lyn Chevely and Joyce Sutton’s Abortion Eve, the first comic about abortion, and Mary Wing’s Come Out Comix, the first comic created by and for queer people. Women like Chevely, Sutton, Wing, Trina Robbins, and Joyce Farmer to tackle topics the male-dominated early underground titles like Zap didn’t. Their thoughts were not thinkable by the (mostly) straight and white male cartoonists of the time and opened the doors for more queer-themed comics like Gay Comix’s Gay Comics anthology and his acclaimed Stuck Rubber Baby graphic novel.

Transgressive works don’t often make for easy reading or viewing and they don’t often age well. But they unlock gates and to allow future generations to trod on sacred ground. It’s too early to say whether Sad Sack will do that. But at least its creators are still thinking the unthinkable.