The Amateur Creator’s Union: My Internet Before the Internet, Part 1

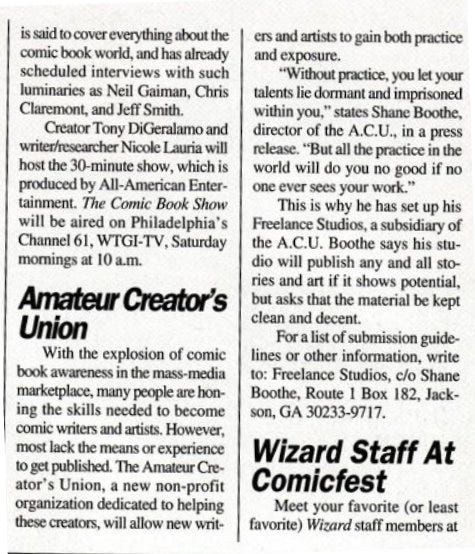

One of the most important moments of my youth came one October day in 1993 when I spotted the following news story in Wizard magazine # 27:

One of the most important moments of my youth came one October day in 1993 when I spotted the following news story in Wizard magazine # 27:

The Amateur Creator’s Union, a new non-profit organization dedicated to [helping inexperienced comic book creators[ will allow new writers and artists to gain both practice and exposure.

“Without practice, you let your talents lie dormant and imprisoned within you,” states Shane Boothe, director of the A.C.U., in a press release. “But all the practice in the world will do you no good if no one ever sees your work.” […]

“Boothe says his studio will publish any and all stories and art if it shows potential, but asks that the material be kept clean and decent.”

I had created several comic characters at this point and was doing my best to imitate the style of my favorite comic artist, Rob Liefeld. I had a pretty good sense that I wasn’t ready to draw for Marvel or DC, but I thought I had cool characters and thought I was a good writer. Of course, all those characters were derivative and my writing was awful. But I didn’t know that then. I was coming up with the sorts of characters and stories that I, as a 12-year-old boy, wanted to read: violent antiheroes having long, bloody fights with even more violent villains. The promise of having an outlet for my work was a dream come true.

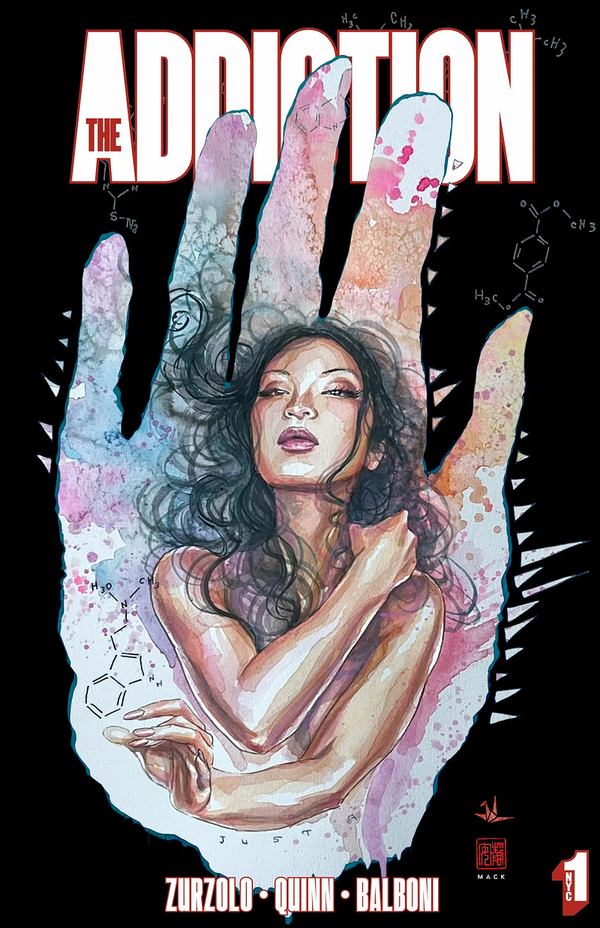

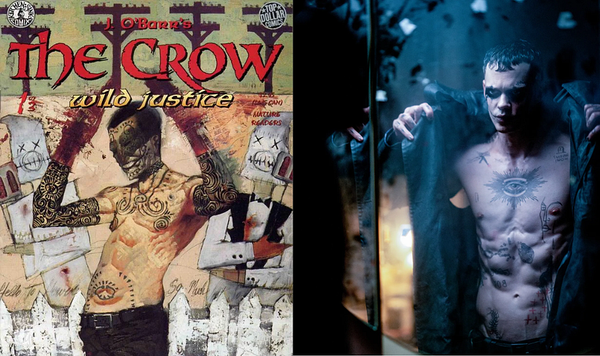

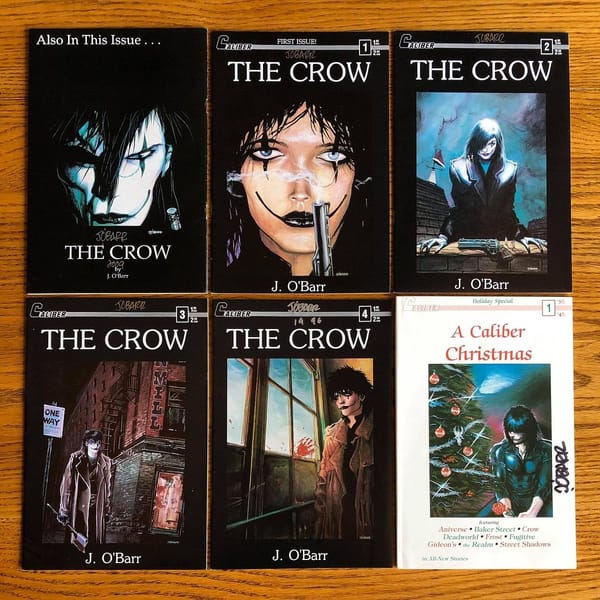

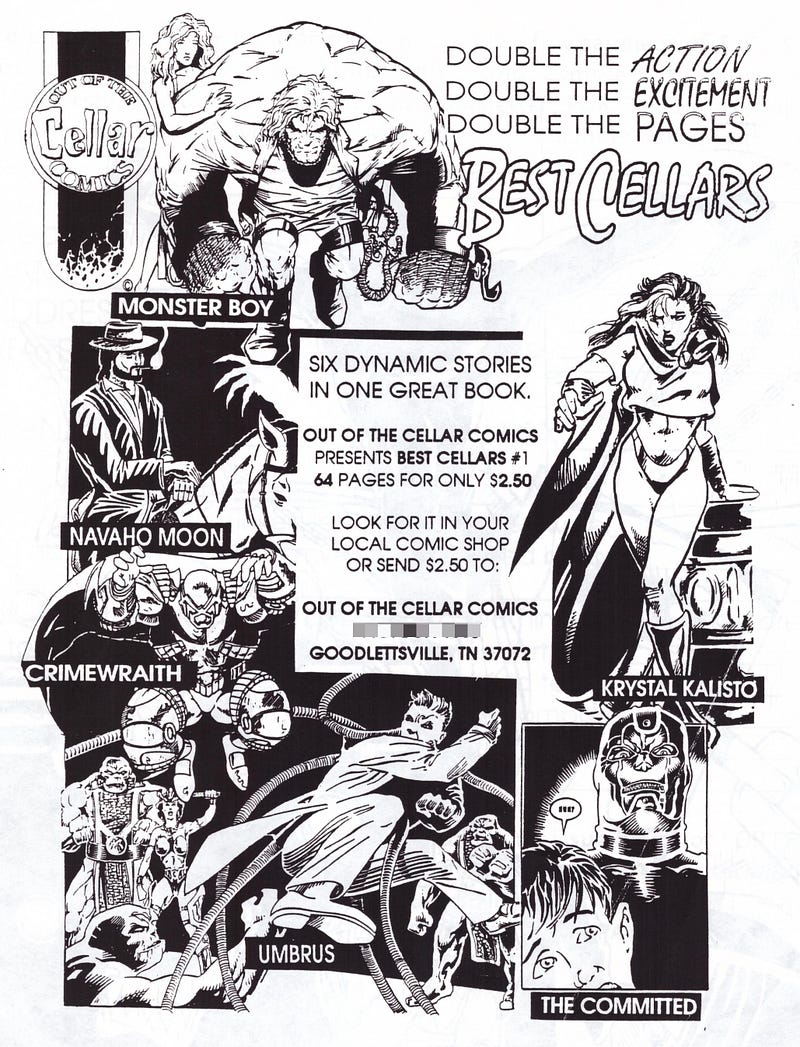

The ACU sounded too good to be true. But it made good on its promise. In fewer than two years of existence, it published dozens of photocopied “ashcan” comics, a more professionally produced black and white anthology called Sketchbook, and 11 issues of its newsletter Portfolio. Within those pages, the ACU published early work by several people who went on to professional careers in comics, including Pat Quinn, Ale Garza, Michael Ryan, Tom Mullin, Philippe Xavier, Caleb “Cabin Boy” Salstrom, Jaymes Reed, and Chris McCarver. Mark Pajarillo was also a member, but I wasn’t able to find any of his work in the ACU publications I have. ACU member Chuck Angell published the first comics work of Eric Powell, the creator of the perennially popular The Goon series, in an anthology advertised in Portfolio. Other ACU members, including Samal McNealy, Craig Strzelecki, Terry Parr, and Radames Malave still do comics as well. The ACU also published work by people who went into other creative careers, including NCIS: Los Angeles actor and The Boys television series writer Anslem Richardson, designer and photographer Chad Michael Ward, film and video game concept artist Pat Razo, illustrator Edward Bourelle, and graphic artist Bill McEvoy.

“My memories of that time are pretty positive,” says Quinn, who’s probably best known for his run on GI Joe at Devil’s Due Publishing and is now associate chair of sequential art at the Savannah College of Art and Design. “I was excited to know that there was a community of like-minded people trying anything that they could to break into the industry. It was always a thrill to get something in the mail that was associated with the ACU.”

“Nobody hired me based on seeing ACU material,” he says. “What it did help with were the intangibles: goals, producing work, deadlines, communication — all critical skills that I don’t think that I was aware that I was working on. Also, seeing your work in print out in the world is a good gut check. No matter how proud you are of the work, you still flinch a bit when it’s out there or at least I do. There were some talented folks in there.”

I never did get any work published through the ACU. But I did get something more important. I got a community.

When the ACU started, I was living in the small Texas panhandle town of Dalhart. The local comic shop closed about a year previous (my dad bought on its entire inventory, but that’s another story). I bought most of my comics from a convenience store near more grandmother’s house. I only had one friend with any interest in comics, and I think he was mostly only interested because I kept shoving them in his face. The internet existed, but it was early days. I’m not sure there was a single internet service provider in Dalhart in those days. At any rate, I was years away from having my first dial-up internet account. In short, I didn’t have anyone to talk comics with.

It turns out that ACU founder Shane Harper (nee Booth) was in a similar situation. He was 14 years old and lived in Jackson, Georgia. Like me, he was a comic fan and aspiring artist and writer. Shane knew that, traditionally, comics creators made many of their industry connections through conventions and comic shops. But the nearest comic shop was a 40 minute drive away. “I realized if I was going to do comics as a career, I was going to have to find people to help,” he says. “I couldn’t drive, I couldn’t go meet up with people in a bigger city.”

“I knew there were other kids, and adults, who wanted to make comics but we didn’t have a way to get together,” Shane says. “I thought the best way to get people together was a newsletter with classifieds.”

He had a little desktop publishing experience from working for his school’s yearbook, and had started a couple of fanzines. And unlike most 14 year olds, he actually had some money in the bank from a settlement over a traffic accident. So he typed up a simple press release and sent it to Wizard and, to his surprise, the magazine actually published a news story based on it. “It was very pretentious, but they ran with it,” he says.

Wizard was by far the largest comics publication at the time. Based almost entirely on that single news story, more than 200 people signed up for ACU memberships. “We had a broad range of people signing up,” Shane says. “Looking back, a lot of the members were probably teenagers or under 25. We had a few ‘real adults’ like Tom Mullen and Ron Riley, but our membership skewed young.”

Razo says he was about 14 when he signed up. “If I recall, my dad told me about it,” he says. “I work in film now so I guess the hard work paid off!”

Shane was far from the first to found an organization for amateur comics creators. Amateur publishing is as old as fandom itself. In the early 19th century, Lord Byron fans wrote their own variations of the romantic poet’s work that they sometimes copied them into each other’s “commonbooks.” By the early 20th century, Sherlock Holmes fans were publishing their own fan-fiction.

From the fanzines that published early work by the likes of Roy Thomas and John Byrne, to Comico’s Primer anthology that introduced Matt Wagner and Sam Kieth to the world, amateur publishing has long been a staple of the comics industry.

In fact, the comic book industry was practically founded on the idea of publishing amateur work. New Fun, widely considered to be the first modern comic book to publish original material, was assembled by the company that eventually became DC Comics to publish comic strips by young creators that had been rejected by newspapers. Founder Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson’s idea was to buy the material and then license it out to newspapers. It might sound like a strange idea to build a business around given that the strips had already been rejected by newspapers. But the company published Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster’s Superman stories, which they’d originally pitched to newspaper syndicates. And, well, you don’t really need me to tell you how well that worked out.

Several “APAs” (amateur press associations) were still in operation at the time, but I didn’t know about them. There weren’t ads for APAs in Wizard. The magazine published fan art and encouraged readers to send pitches for articles, so in that sense it was a place where artists and writers could get their feet wet. But it didn’t build community. It wasn’t a place for creators to find each other for collaborations.

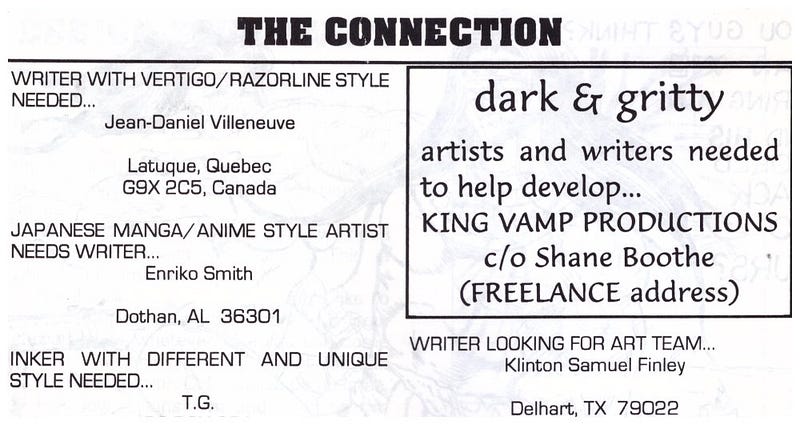

That’s exactly what the Amateur Creator’s Union was. It published a near-monthly newsletter called Portfolio that, in addition to running art and articles (with a much lower bar for inclusion than Wizard) but also a classifieds section called “The Connection” where artists and writers could seek collaborators. I ran an ad in the 4th issue of the newsletter looking for artists, and sent my scripts to several artists who said they were looking for writers.

I only had one bad experience with someone being rude to me after I sent him what I recognize in hindsight was really poor work (remember, I was 12 years old). But everyone else was way nicer than they probably should have been. Many people included their phone numbers in their ads, so I started racking up enormous long-distance bills calling other ACU members. Through the ACU, I was able to correspond with many other comic fans and comic creators and, for the first time in my life, have wide-ranging and serious discussions about the medium. I finally had people I could bounce ideas off or share opinions on the latest DC crossover with. I got to hear people talk about what they liked or didn’t like.

At the time I thought of all the phone calls as business: I was trying to put together my own line of comics. Shane announced in Portfolio that the ACU encouraged the creation of imprints, just as Image Comics had multiple imprints like Homage Studios (which later split to become Wildstorm and Top Cow) and Extreme Studios. But instead of trying to create a shared universe, as Image Comics did, each ACU imprint would be its own universe, so the 200 some ACU members wouldn’t have to worry about continuity.

I came up with my own imprint I called Aftermath Entertainment (this was three years before Dr. Dre would use the name for his record label). I had dozens of character and story ideas — all derivative — and cranked out scripts with reckless abandon. I could easily write an eight-pager in an afternoon. I probably had years worth of stories plotted out. They weren’t sensical, let alone good, but I miss the effortless productivity of late childhood.

I wasn’t able to recruit many artists. They all politely said they were too busy with other projects. I called Chuck Angell, who went on to publish Eric Powell’s first work, a lot because he had an 800-number at his work. He was always super nice. Two artists, Bobby Hewitt Jr. (who actually interned at Marvel) and Terry Parr, agreed to draw pin-ups for me. Bobby drew a pin-up of a Green Lantern knock-off I created called Starblazer. Terry drew a pin-up of my mutant superteam DNA Force. Sadly I can’t find either pin-up right now. Another guy, Luis Alonso, agreed to ink my DNA Force stories if I ever found a penciller. I made my own newsletter for Aftermath. I think it was text only, two or three pages, printed out on my dot matrix printer and mailed out to people like Bobby, Luis, and Terry. I probably only did two or three “issues” or so of that, but it was the first publication I ever published.

In retrospect, it’s easy for me to see that I was constantly finding excuses to call people because, well, they were the only people I could talk with about comics. I spent hours talking to a guy named Erik Hicks in Florida. I don’t remember what excuse I found for calling him all the time since he was a writer developing his own imprint (as far as I know, the only thing he got published was a pin-up of his character Lace in Jaymes Reed’s Hydra, Mistress of the Sea ashcan). But really I just liked talking with him.

It’s difficult to explain what this was like to someone who has never had the experience of finding people to geek out on a hobby or passion that you’ve never been able to discuss with anyone else. To this day I’ve never met any of the people I corresponded with through the ACU, but I still think of them all as long lost friends.

Have any memories of the Amateur Creator’s Union you’d like to share? Get in touch with me at klintfinley@gmail.com