The Crow Creator James O’Barr’s Early Years

Part 1: The Crow Creator James O’Barr’s Early Years

- Part 1: The Crow Creator James O’Barr’s Early Years

- Part 2: The Crow and Caliber Years

- Part 3: After The Crow: The Works of James O’Barr

Note: I might receive a cut of any referrals to Mycomicshop.com.

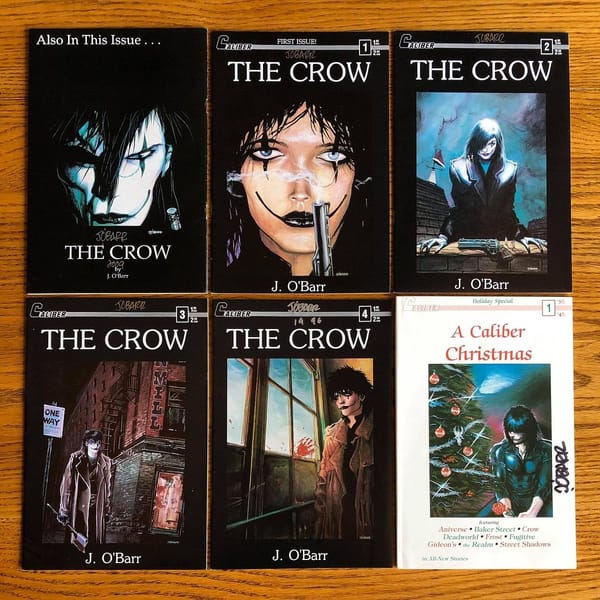

Even if they sold fairly well, most Outlaw Comics existed on the fringes of the comics industry. But there was one Outlaw title that not only managed to garner attention far outside the niche of people who read black and white comics in the late 1980s and 90s but also became a bona fide pop culture sensation. The Crow, first published by Caliber Press in 1989, spawned a movie franchise, television series, and action figure line. Goth kids the world over painted their faces in imitation of the comic/film’s main character. For many of us, The Crow was a portal into a world that we knew must exist but we hadn’t had any access to yet.

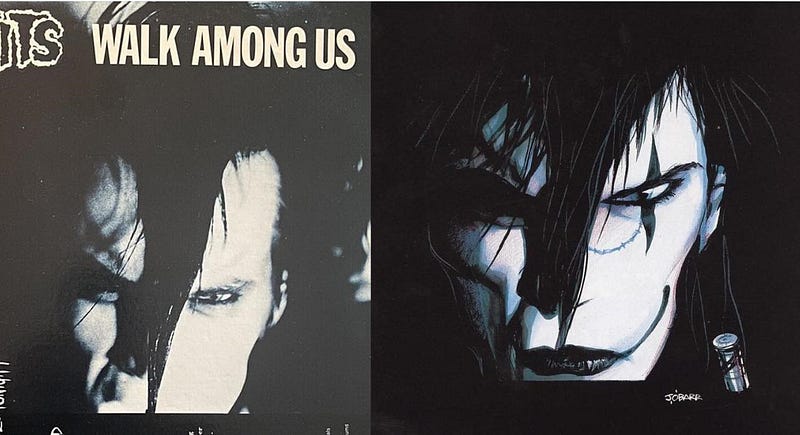

The Crow was, along with Love and Rockets and Sandman, one of a few titles in the 1980s that was not only shaped by the punk, post-punk, and new wave subcultures, but shaped those subcultures as well. And it did so at just the right time.

Underground Comix made comic books cool in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Marvel and DC have a long history of trying to tap into counter-cultural currents, of course. But it was the Undergrounds, which were created by the counter culture for the counter culture, that truly captured the zeitgeist. But by the 80s 60s counter culture was superseded by new subcultures that emerged out of punk rock.

Throughout the 80s comic creators applied punk and new wave aesthetics, mostly as a way to decorate villains. But while they brought the aesthetics of punk into their comics, they didn’t do much to bring counter-cultural, anti-authoritarian, or gothic romantic sensibilities into the work. Alan Moore, meanwhile, brought the sensibilities of punk and goth to his work but, outside of his personal image, not so much the aesthetics.

The Crow creator James O’Barr, Love and Rockets creators Los Brothers Hernandez, and Sandman writer Neil Gaiman actually lived the punk and goth lifestyle and were able to bring not just a punk aesthetic but authentic punk and gothic sensibilities to their works that their predecessors simply didn’t.

The Crow managed to ride and shape the goth subcultural wave of the 80s and 90s, bringing new readers into comics and helping define the Outlaw Comics aesthetic. But it was a long and painful journey for O’Barr.

Background

“James O’Barr’s biological mother had been repeatedly in and out of mental institutions, jails and hospitals all of her adult life,” the biography on his old official website read. “When the social workers came to retrieve the newly-born infant James O’Barr (not his actual birth name) and inquired about his exact age, she could only say that he had been born some time between Christmas Day and New Year’s Eve. And so it was that James O’Barr was assigned a birthday of January 1st, 1960, and taken with his older half-brother to an orphanage in Detroit, Michigan.”

He and his brother spent much of their youth in the orphanage, except when they were “loaned out” for the weekend. “It was never for very long and it wasn’t a good situation,” he said in an interview included on the 2000 release of The Crow DVD. “Some of these people shouldn’t have been allowed to have pets, let alone children. I think there was a lot of monetary incentive for people to do that sort of thing, they would get $100 to take a kid for a weekend.”

It took years to find a family willing to take both O’Barr and his brother. “We were there for seven years because my brother had TB. People were terrified of TB back then,” O’Barr said during a Q&A session at the DiNK Denver: Independent Comics & Art Expo in 2018. “So they were like ‘if you want the cute blond-haired one you have to take the sick one too.’”

Life in the orphanage was often isolating. “None of the other kids [at the orphanage] would play with me,” O’Barr said during the DiNK Q&A. “I didn’t understand racism back then but I was treated more favorably than the Black kids. They had to sleep in a ward, I had my own room. So obviously they had resentments.” With little else to do, he turned to art. “By the time I got the coloring books they’d all been fucked up, so I would just go around and any piece of paper, I would tear flyers off the wall and just draw on the backs of them,” he explained. “I found ways to entertain myself.”

O’Barr has described his adoptive parents as blue-collar folks from the south. His father was a bus driver and his mother worked at IHOP. She couldn’t afford a babysitter, so he said she dropped him off at the movie theater next door to the restaurant and he would spend the day watching the same movie over and over. “The first time I’d watch it. The second time I’d study, the third time I’d pick it apart, try to understand why they chose a particular camera angle,” he said in an interview with Panel Borders podcast in 2014.

But as a creator, he was drawn more to comic books. “I loved to draw and I loved to tell stories, comics are the one medium where you get to do both,” he said in an interview with the Motherfucker in a Cape podcast in 2018. “If you make films, it’s a huge effort with hundreds of people and always there’s cutting corners and negotiations but with comics, I have complete control, it’s specifically my vision.”

“I was always interested in, not the superhero stuff, the monster comics, Creepy and Eerie, that type of stuff,” he said during a Q&A session at the DiNK Denver: Independent Comics & Art Expo in 2018.

But his new parents didn’t support his artistic ambitions. “They thought drawing was the equivalent of playing cards, it was just something to do,” he said in 2000. “I reached an apex in my teenage years where I wasn’t allowed to draw in the house because I was wasting so much time. I was told to get a real job.” He did his drawing at the library, or at school.

O’Barr stuck with art and soon he was taking his portfolio to comic conventions, where he said he received a scathing dismissal from Dave Cockrum. “I showed him my portfolio, and he flat-out told me I had no talent, I was wasting my time, and that I should take up truck-driving,” he told Comic Scene in 1992.

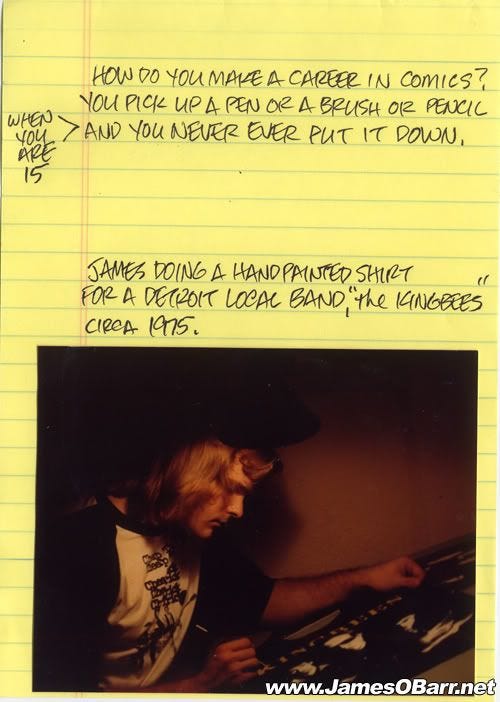

He found more encouragement from underground cartoonist Vaughn Bode, whom O’Barr met when he was around 15. “Vaughn took a personal interest in me,” O’Barr told Nerd Team 30 in 2018. “And even though our styles are polar opposite, I learned a lot from him about staging, foreground elements, pacing and he told me about a lot of other artists to look at that were before my time.”

You can actually see the Bode influence pretty clearly in his work, especially the way he draws faces, especially women’s eyes.

O’Barr fell in love at the age of 16. “I felt like God has his elbow on my neck my whole life,” he said in 2000. “She was like an angel to me, she was everything I ever wanted. I thought ‘I did it, I got to the end of the race’ and for not giving in, not surrendering through that 16 years of difficulty I finally got the prize.”

“She was like the exact opposite of me,” he continued. “I was dark and brooding and really sarcastic, venomous. She was this bright white light, I never heard her say a word against anyone. If I were to verbally attack anyone, she would point out their good points. So it was like positive and negative, we just fit together perfect.” They got engaged and planned to marry after graduation.

Meanwhile, in 1978, O’Barr landed his first published work: a short sci-fi story called “Incident on Planetoid 7” in issue 4 Gasm, a Heavy Metal-style magazine. O’Barr has said in a few interviews that he sold his first story to Heavy Metal when he was 17. But O’Barr wasn’t published in any Heavy Metal issue in the 70s or early 80s, nor does it seem likely that O’Barr would have been featured alongside the much better known and more accomplished artists that appeared in that magazines pages at the time. It’s more likely that O’Barr confused Gasm for Heavy Metal, possibly mistaking Gasm for a sister publication to Heavy Metal.

In “Planetoid,” a human gang kidnaps a girl. But before they can leave the planetoid, a rival gang of aliens that look a bit like Skrulls blow up their ship and take the girl. The human gang storms the rival gang’s ship and kill the leader. The girl is now more than happy to sleep with the human gang’s leader. It includes an apparent KISS homage or parody as well. O’Barr later said the story was inspired by A Clockwork Orange — the gang are essentially the droogs in space.

It’s rough, misogynistic work, but it displays two tropes that would be common in the artists’ future work: music references and longhaired glam-goth protagonists wearing. “Jim O’Barr, or ‘Zen,’ as he calls himself, is a relatively new and young artist who you’ll probably be seeing more of. Although somewhat crude, his work has high energy, and I think ought to be included here. Besides, in five years, you’ll all be dyeing your hair orange and wearing safety pins through your nose. Don’t laugh,” editor Jeffrey Goodman wrote in the introduction to the issue.

The story was dedicated to his fiancé. Tragically, her life was cut short by a drunk driver in 1979.

O’Barr was lost. “I joined the seminary for six weeks,” O’Barr told the Kansas City Star in 1994. “I wasn’t overly religious. I just didn’t want to think. I wanted some structure in my life.” He found that structure in the Marine Corp.

“Once they found out I could draw they put me on special assignment redrawing all these manuals that were essentially the same manuals they had been using since World War II and there was all sorts of racist shit in them, the Germans were all wolves and the Japanese had the coke bottle glasses and the buck teeth,” he said on the Motherfucker in a Cape podcast. “I had to redraw all this stuff without the racist elements.”

One that left a particular impression on him was a manual on the disposal of dead bodies and body parts, which he says influenced the way he depicts violence. “I don’t believe in stylized violence, I think it should be as ugly as possible,” he told Panel Borders.

Living in Berlin (across the street from the strip club for which Revolting Cocks’s album Big Sexy Land was named) and traveling to the UK helped O’Barr expand his musical palate. “When I first heard Ian Curtis and Joy Division I instantly knew that I finally found what I had been looking for,” O’Barr said in a promotional interview for The Crow: City of Angels soundtrack. “Nothing was sacred; they would talk about any type of pain with absolute honesty. I felt like I had a partner giving me support.” Goth and post-punk became major influences in his work, which is full of references to bands like Joy Division, The Cure, and Big Black. “I was probably more influenced by music than I was by any other artwork or things that were around me at the time,” he said in an interview in The Crow Magazine in 2000.

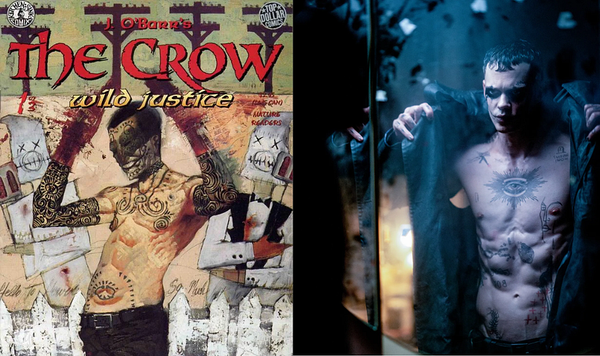

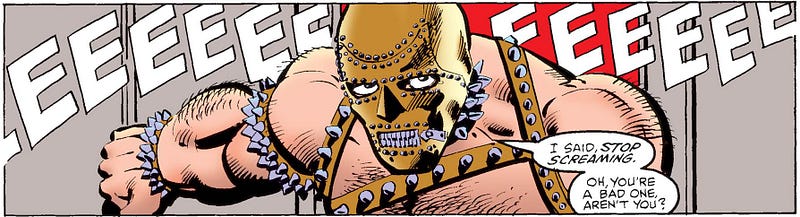

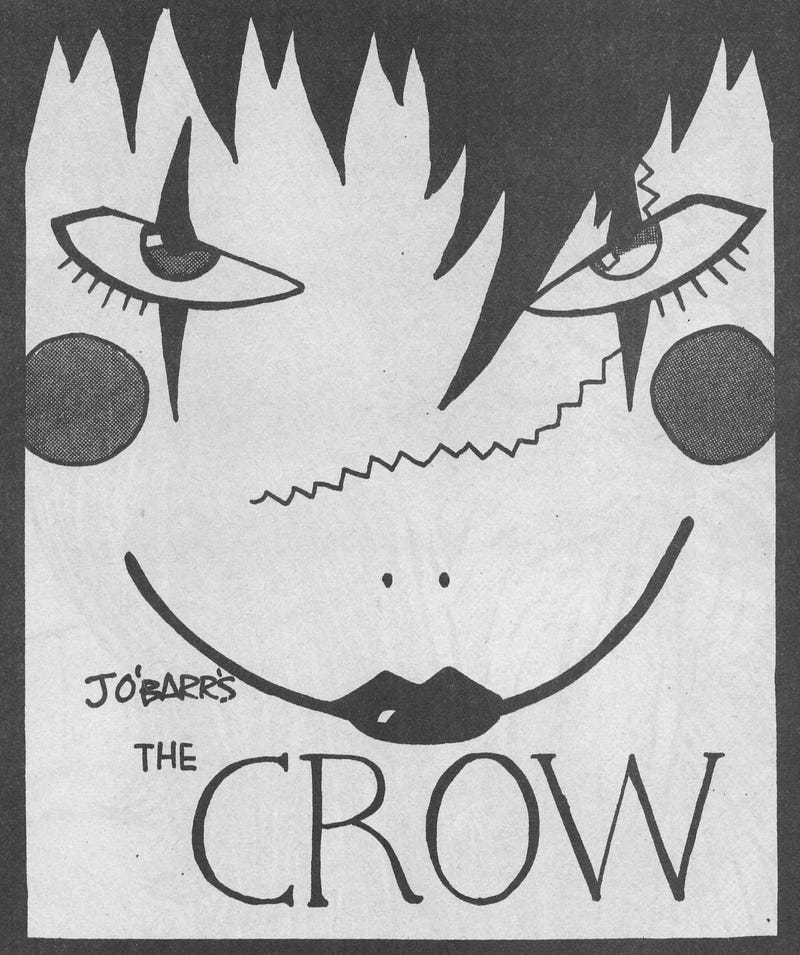

O’Barr said many times that he was inspired to start working on The Crow while in the Marines, inspired in part by the death of his fiance and in part by a news story published in 1979 about a couple killed over a $20 engagement ring in 1979. Although the final look of The Crow was heavily influenced by Bauhaus singer Peter Murphy (for the face) and Iggy Pop (for the body), his earliest drawings of Eric Draven show little of this influence. The first drawing, dated 1980, depicts Eric wearing a mask instead of make-up. By the second drawing, O’Barr had ditched the mask in favor of make-up.

After the death of his father in 1980 or 1981, O’Barr received an early discharge from the Marines and returned to Detroit “with full intent and focus to kill the driver” who took his fiance’s life, according to his old bio. “But fate had other plans,” the site read. “And James once again found emptiness upon learning that the driver had already passed from this world by natural causes.”

O’Barr channeled all his pent-up rage into The Crow. “I thought it’d be a catharsis if I could channel all this anger and frustration onto paper,” O’Barr told the Kansas City Star. “And it turned out the exact opposite. I was narrowing my vision to the point where that was all I could concentrate on, and every page became a little death.”

Early Comics Career

After his stint in the Marines, O’Barr worked day jobs at auto-shops while trying to break into the comics industry and trying to get The Crow published. It’s not clear how much of it he completed before the first issue’s publication in 1989. Late Caliber Press publisher Gary Reed wrote that O’Barr had at least 14 pages done when they met in 1988.

O’Barr told Comics Scene that the only publisher that expressed any interest in The Crow was Barry Blair’s Aircel. Aesthetically this would have made sense — Aircel published a few punk-flavored comics like Samarai and Warlock 5. But O’Barr said they wanted him to make major changes to the book. “It was obvious they missed the entire point of the series,” he said. “I knew there was an audience out there who could identify with the book’s pain and angst. The idea of twisting the character into a Punisher clone was unthinkable. So I put it on the shelf, where it lay for 10 years.” He’s often said he thought of The Crow as a personal project that would never be published.

O’Barr has mentioned in a few interviews that he was in one or more bands. I haven’t been able to find any information about this, apart from him contributing lyrics to John Bergin/Trust Obey’s The Crow comic soundtrack and, more recently, writing on a song on These Machines are Winning’s album Kuru. Any information on this front would be appreciated.

He’s also mentioned that he also wrote music reviews during the 80s or early 90s. “In Detroit where I’m from, I had done concert reviews of the new wave and punk bands, or the Nine Inch Nails-type bands, and I’d become friends with a lot of them…I’d given them copies of my books to read on their tour buses,” he told The Crow Magazine. More recently he has claimed to have written for Spin.

“I had a great editor over there, Dave Eggers who went on to bigger and better things,” O’Barr told Nerd Team 30 in 2018. “Pulitzer Prize winner Michael Chabon worked there as well.” He also said during the DiNK Q&A that he wrote for Spin and interviewed Rage Against the Machine. This is puzzling on multiple levels. Eggers was a teenager in the 80s. He did have a column for Spin but not until the early 2000s. Chabon told me on Twitter he never wrote for Spin. I can’t find any reviews or articles credited to James O’Barr, Jim O’Barr, J. O’Barr, Zen, or Johnny Zero in the Spin archives hosted on Google Books. Given his confusion of Gasm and Heavy Metal, it’s possible he wrote for a different publication. In 1991, O’Barr told Terra X that he had written “an occasional short story or essay for small press magazines.” Eggers briefly attended University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign in the 80s, Chabon went to Carnegie Mellon University, and O’Barr says he attended Wayne State for a time. It’s possible O’Barr wrote record reviews for a student publication that was anthologized alongside writings by those students at mid-western colleges, not unlike the way some of Joe Vigil’s political cartoons were featured in an anthology of student journalism works. If anyone could shed light on this I’d appreciate it.

O’Barr also claimed in the Nerd Team 30 interview to have designed a logo for Skinny Puppy’s 1987 album Cleanse Fold and Manipulate. I asked Skinny Puppy founding member cEvin Key and longtime Skinny Puppy packaging designer Steven R. Gilmore about this and they both denied having ever met or worked with O’Barr on anything. The wordmark for Cleanse Fold and Manipulate is just the name of the album set in Garamond — not the sort of thing I’d expect from O’Barr — and the Skinny Puppy wordmark is one that had been used for years prior to this album. I’ve not been able to reach O’Barr for any comment for this article.

Nine Inch Nails frontman Trent Reznor did confirm in an interview in Kerrang in 1994 that he knew O’Barr prior to contributing to The Crow motion picture soundtrack, so O’Barr clearly was connected in the mid-western music scene at the time.

In addition to the music scene, O’Barr got into car culture at this time. “In 1983 I bought my first Cuda, a 1972 midnight blue hardtop with a 340 workhorse engine and a 727 torque flight trans for $1,200,” he wrote in The Ride: Inertia’s Kiss in 2011. “I named it Godzilla and it lived up to its name.” He bought two more Barracudas over the years, naming them Rhodan and Rimbaud.

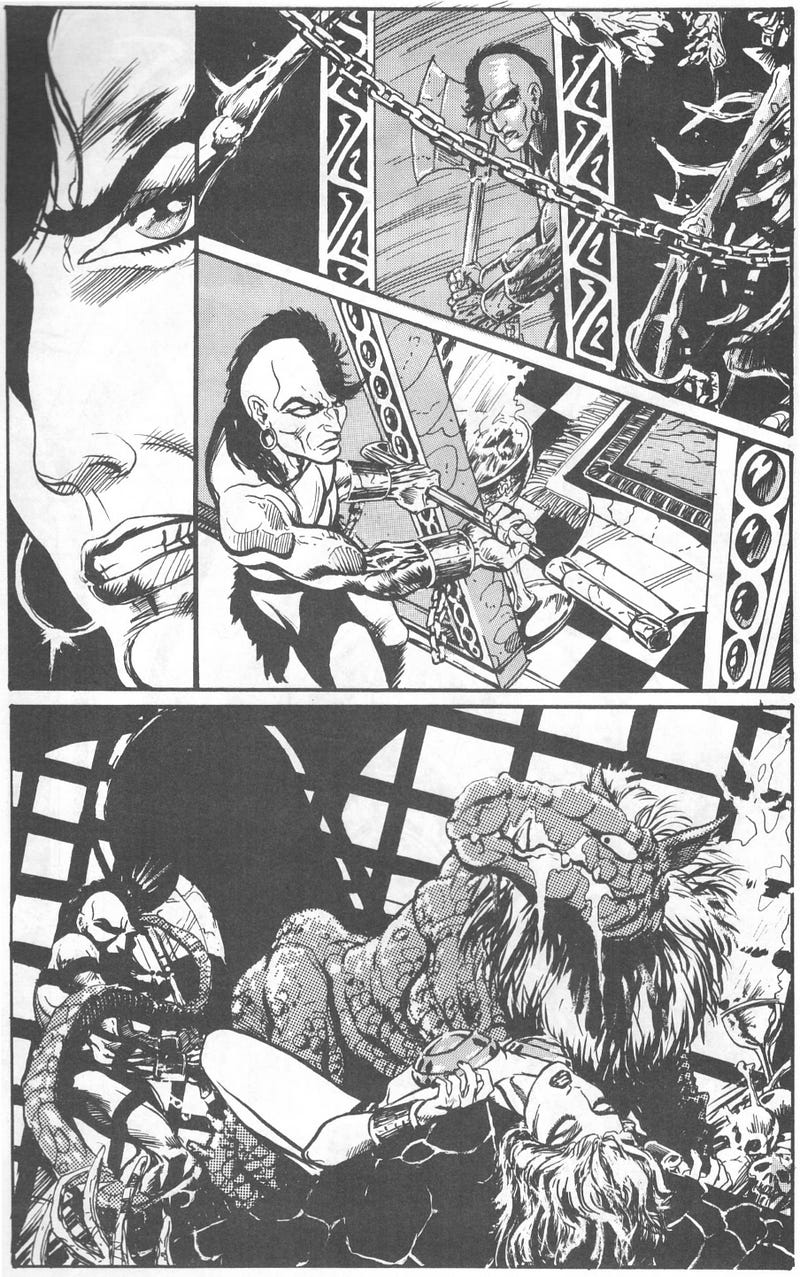

Car culture inspired O’Barr’s only known comics work published in this period: “G Forces,” published issue 4 of the magazine-format Savage Tales anthology series from Marvel. This piece is far more accomplished than the one in Gasm, and is arguably stronger than the first issue of The Crow, which might suggest that parts of the first issue were completed prior to “G Forces.”

It’s a silent story featuring a guy who looks a bit like O’Barr driving a muscle car across a post-apocalyptic terrain. In Inertia’s Kiss he described it as “basically me and my Cuda, with a phantom pet along for the ride.”

I wonder if it’s meant to take place in the same universe as his later story “Slave Cylinder” (based on a short story by Jeff Holland called “LSD Test Animal”), which might take place in the same shared universe that O’Barr’s and Bergin’s shared universe from “Io,” “Frame 137,” Golgothika, and Wednesday. It continues O’Barr’s habit of including glam-goth guys as protagonists and establishes another frequent O’Barr trope: muscle cars. Note that the license plate in this story reads “Rhodan.” Eric’s license plate in The Crow is “Godzilla” and Henry’s plate in “Slave Cylinder” first reads “Diplomat” then changes to “Monster Zero” a few pages later.

O’Barr wrote in the introduction to his anthology Savages that editor Larry Hama bought a few pieces O’Barr had drawn on-spec for Savage Sword of Conan and offered to buy “as many Conan pin-ups I could draw in two months.” But they were rejected by Hama’s successor on the title. “The new editor expressed two opinions: one, that he thought my Conan looked like a fag prince; two that the only people that read Conant were bikers and guys in jail who did not like their barbarians ‘swishy,’” O’Barr wrote. Some of this work dated from this period may have been published in Savages.

O’Barr also drew an X-Men story intended for Marvel Fanfare that never saw print. The X-Men drawing above might be from this, or it might be from a set of spot drawings he says he sold to The Comics Journal (I don’t know if any of these were ever published in the Journal or elsewhere).

The first issue of the original Caliber Rounds, published in 1988, said that O’Barr was a student at Wayne State University at the time, something he’s mentioned in many interviews (sometimes exaggerating his pre-med major into “medical school”). I’m guessing he started at Wayne State right after the Conan rejections. Hama’s last issue as editor of Savage Sword was # 140, cover dated September 1987 (which means it was published in August and assembled before that), so he could have started in the fall of 1987.

In 1988 he finally found a publisher for The Crow, a move that would lead to only more pain in the future.

More to come…

Links

John Bergin’s Instagram account (The Crow drawing 2)

The James O’Barr Collector (Lots of scans and pics)

Shattered in the Head (A James O’Barr fan site)

James O’Barr Series

- Part 1: The Crow Creator James O’Barr’s Early Years

- Part 2: Caliber Comics (Forthcoming)

- Part 3: After The Crow: The Works of James O’Barr

- More on Outlaw Comics

If you want to follow this series, follow Sewer Mutant here on Medium, or subscribe to my email newsletter: