The Secret Origins of Avatar Press

I’ve been a professional journalist for more than a decade. I’ve covered big, powerful companies like Facebook, Google, and Comcast. I’ve…

The Secret Origins of Avatar Press, The Last Outlaw Publisher

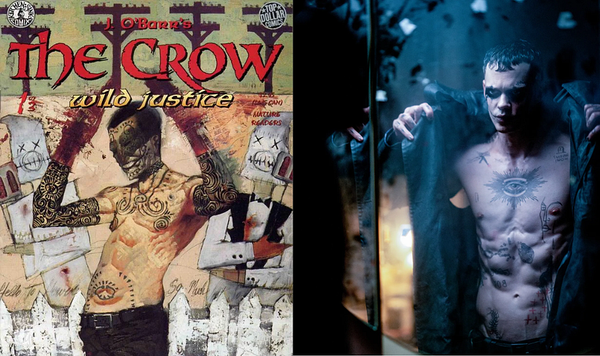

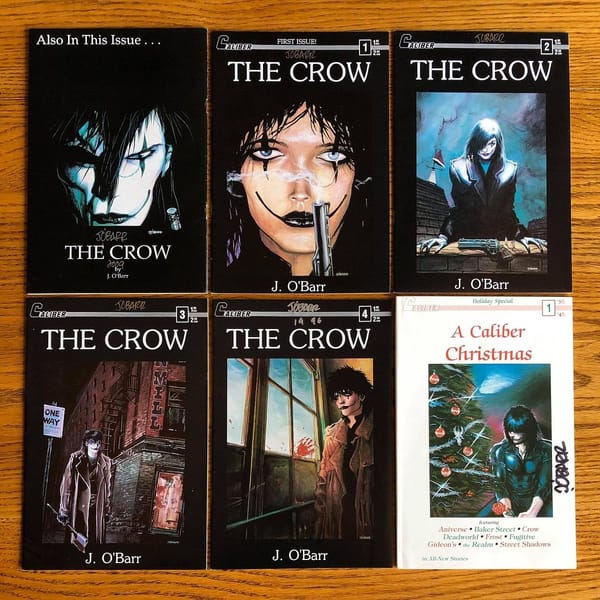

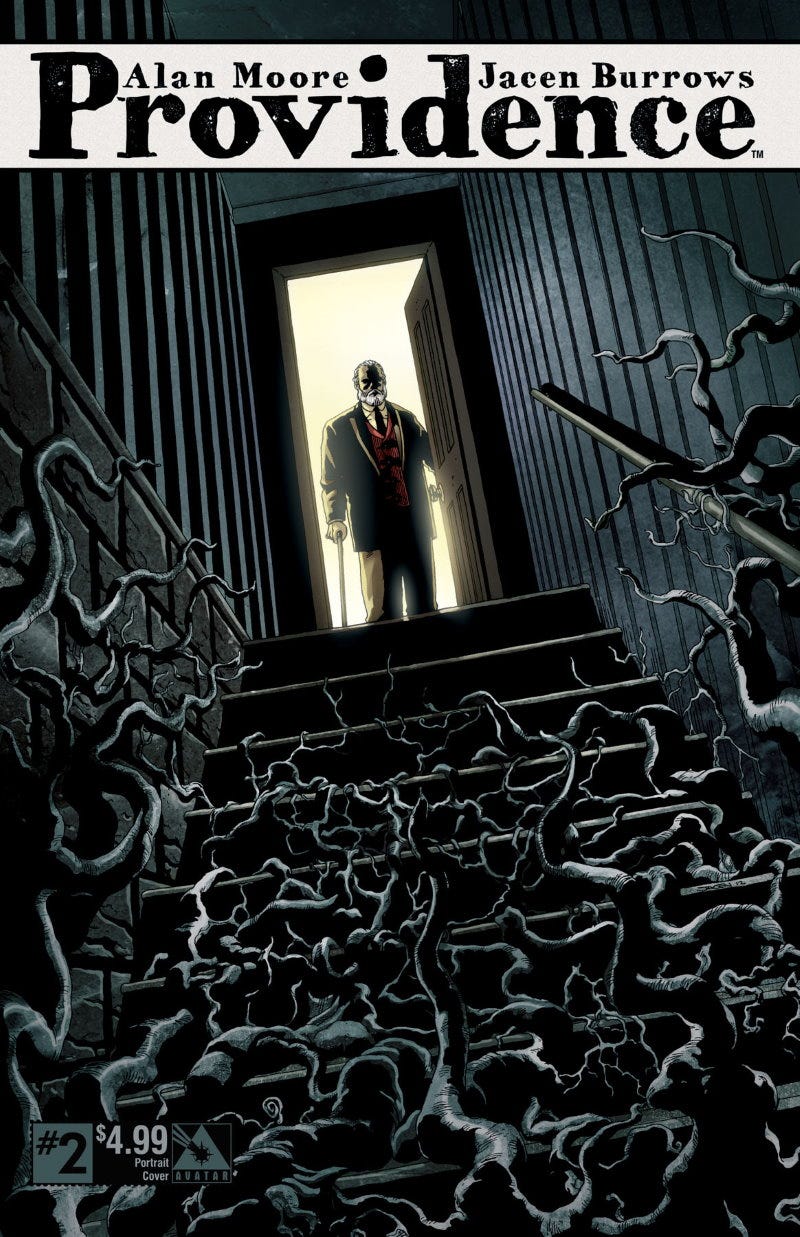

I’ve long been puzzled by Avatar Press’s origins. It appeared seemingly out of nowhere in the mid-90s to publish a staggering number of titles that had previously been published elsewhere. Most of these were “Bad Girl” comics, like Widow (London Night Studios), NiraX (Entity), Hellina (Lightning), and David Quinn and Tim Vigil’s long promised female Faust spin-off (Rebel Studios). But some came out of left field, like Dreamwalker. Later it transformed itself into the home of projects by many high-profile, critically acclaimed writers, including Alan Moore’s Providence, Warren Ellis’s Black Summer, and Garth Ennis’s Crossed.

Where did this company come from? Unlike most publishers, its website has no “About” page and no bios of its founders. My multiple requests for comment from the company and its founders went unanswered. Other sources were reluctant to talk.

Why the apparent secrecy? When I strung together the company’s history from news clippings, public records, old press releases, blog archives, and a few brave souls willing to talk, I found some old bad blood but nothing outright sinister. It’s well known that Avatar owns Bleeding Cool, one of the web’s leading comics and pop culture news sites. Its writers dutifully disclose the fact whenever they mention Avatar. And it’s not exactly unheard of for publishers to also own news outlets. Fantagraphics owns The Comics Journal and, for a time, Lionforge owned The Beat.

It’s less well known that Avatar and comics mail-order business Comic Cavalcade are owned by the same people. Comic Cavalcade is usually referred to by Avatar as its “retail partner” as opposed to “sister company,” and it’s not typically mentioned in the few bios of founder William Christensen I could find. But it’s been mentioned on Bleeding Cool, and the two businesses have always shared an address. So it’s not exactly a secret either. None the less, even dedicated Avatar fans seem to know don’t seem to about their relationship. I can’t see any reason to keep this quiet. It’s pretty common in this industry for retailers to start their own publishing companies. Dark Horse is a prime example, and its sister retail outfit Things from Another World is still kicking. Caliber and Dynamite are two other notable examples.

As I dug into the history, instead of uncovering a dark secret, I found myself wondering why Avatar is so quiet about its origins. They have a great story of turning a youthful dream into a major industry force.

Before Avatar

In 1989, when he was just 16 years old, William Christensen started Comic Cavalcade as a brick-and-mortar shop in Champaign-Urbana, Illinois with financial backing from his father, the late Richard Christensen, a former executive at the engineering firm Clark Dietz. Around this time, William Christensen met future Avatar creative director Mark Seifert, who became a manager at Comic Cavalcade. “We were both trying to put together our collections of Fantastic Four at the time, I think,” Seifert recalled in a rare interview in 2009. “We quickly became best friends.”

The brick-and-mortar shop eventually closed down and Comic Cavalcade became a mail-order outfit. Comic fans of a certain age may remember their full-page ads in comics and comic magazines throughout the 90s.

Christensen and Seifert began writing for Wizard, by far the largest magazine covering comic books at the time, in 1992. They started out by taking over the “The Wizard’s Crystal Ball” column, starting with issue # 15 (November, 1992), where they tried to predict which books released any given month would be the best investments. After “Crystal Ball” ended with Wizard # 22 they took over the “Marketwatch” column from until # 26. They also contributed the occasional feature or sidebar, including the interview/profile of Alan Moore from issue 27 (November, 1993), a Jack Kirby retrospective in issue 36 (August, 1994), and a short history of arch bad girl Vampirella in 32 (April, 1994). Many of their articles focused on comics history. Starting with issue 35, the pair were credited as “research assistants” on the magazine’s masthead. That lasted into 1998, well after Avatar’s launch.

Avatar seems to have sort of grown out of Outlaw Comics/Bad Girl comics publisher London Night Studios. Between mid-1995 and early 1996, Christensen was credited variously as “Sales Representative,” “Managing Editor,” or “Executive Editor” on the masthead of assorted London Night Studios comics. London Night was growing rapidly at the time, adding both more company-owned titles and creator-owned titles, including titles by Mike Wolfer (Widow), Kevin Hill and Scott Pentzer (Sade, Rose and Gunn), and Tim Tyler (who had originally published London Night’s flagship series Razor through his own company, Fathom).

“It only made sense to me to join forces with another stronger company,” Wolfer wrote in 2007. “Let someone else handle the myriad back-breaking chores associated with publishing while I concentrated solely on writing and drawing.” It seemed like the Outlaw Comics scene was consolidating into a single place, and London Night was it. But it wasn’t meant to be. London Night canceled the Widow: Metal Gypsies mini-series after only two issues, without explanation, despite being one of the Top 100 comics sold the month the first issue was published. Christensen left London Night soon after.

Meanwhile, Comic Cavalcade was “producing” variant covers for a number of companies, particularly bad girls publishers. “My understanding is that Comic Cavalcade would basically partner with publishers to produce their own exclusive variants,” The Comics Journal co-editor Joe McCulloch told me on Twitter. “Occasionally, they would even co-publish the whole issue, like with Entity #1/2 (Nov. 1996).”

Christensen and Seifert also spent some time writing and editing for Chaos! Comics. In 1995, they were credited as editors of the Chaos! Bible and wrote the “Cremator” stories in Chaos Quarterly # 1 -3.

Birth of Avatar

Avatar Press launched in December 1996, with Richard Christensen as publisher, William Christensen as editor-in-chief, Seifert as creative director, and a pool of artistic talent drawn largely from London Night. The company’s first press release said it would start as an imprint of Kirk Lindo’s Brainstorm Comics (the publishers of Vampress Luxura and Vamperotica).

“I struck this deal with Brainstorm publisher Kirk Lindo to allow my company to concentrate on producing a quality product, without having to concern ourselves with handling things on the distribution end in the beginning,” Christensen said in the release. “We will be ending that arrangement soon to strike out on our own.”

The first batch of books announced were:

- Pandora, a bad girl comic based on Greek mythology, written by Christensen and Seifert with art by Richard Pollard and Jude Millien and an alternate cover by Rick Lyon. Pandora became the company’s flagship character, though she now hasn’t had a title in years.

- Lookers, a bad girl comic about a pair of well-endowed detectives, written by Christensen and Seifert with art by Rob Durham and Millien.

- Silent Rapture, a martial arts comic created, written, and drawn by Millien.

Pollard, Millien, and Lyon all previously worked at London Night Studios and became part of the core stable of artists for Avatar’s early years.

Soon the line was re-solicited under the Avatar banner, not Brainstorm, and Donna Mia by Trevlin Utz was added to the mix. Donna Mia had previously been published in full-color by Dark Fantasy Productions and is probably best known for using Neil Gaiman as a character. For the Avatar series, Utz adopted a soft black-and-white pencil style similar to Joseph Michael Linsner’s work in Cry for Dawn (indeed, Linsner fans seemed like the target audience for this book). Donna Mia was the first book to jump from another publisher into the Avatar line-up, but Snowman and Nira X, formerly of Entity, were added soon after.

1996 was a peculiar time to start a new comic book publishing company. The comics speculator bubble burst in 1993. By the end of the year, comics sales were half what they were during the first quarter of 1993, according to data from Capital City Distribution cited by American Comic Book Chronicles. Sales just kept dropping year after year. Capital City estimated the number of comic stores declined from 10,000 in 1993 to 4,500 by early 1996.

Small publishers were hit the hardest. In 1995, Marvel Comics began distributing its comics solely through Heroes World Distribution, a company it acquired in 1994. DC followed by signing an exclusive deal with Diamond, as did several other companies. In July 1996, Diamond acquired its main rival, Capital City. That was a big blow to independent publishers that found Capital City a more hospitable distributor than Diamond, which would drop ongoing titles that failed to reach a minimum of 1,000 copies per issue. Poison Elves creator Drew Hayes, for example, wrote that Capital City was the main reason he was able to survive when Diamond dropped his comic for nearly a year. With that refuge gone, small publishers faced a worse market than ever.

Marvel shuttered Heroes World and returned to Diamond in 1997 after filing bankruptcy in 1996. But the damage to retailers and small publishers had already been done.

“The comic book industry was littered with the corpses of idealistic indy publishers, struck down before their prime by the ravaging, black vacuum created by the rapid retreat of comic book speculators abandoning the market,” Widow creator Mike Wolfer wrote in 2007. “William Christensen knew that it was the perfect time to launch Avatar Press. And I believed him.”

After all, independent bad girl comics like Lady Death and Dawn still sold well, and London Night bad girl characters Razor and Tommi Gunn had been optioned for movies (neither of which has been released to date). “Avatar started in a mid-90’s indy world dominated by companies like Chaos!, Lightning, and London Night Studios — all of whom were top 10 publishers in their time,” Christen said in 2010.

Despite the challenging market, Avatar’s first wave of books sold out and the Avatar line continued to expand, adding, among other titles, Wolfer’s Widow series.

Avatar also brought in another London Night alum, colorist Barry Gregory (Jenni Gregory’s husband), as managing editor. The Gregory family relocated from Mississippi to Champaign-Urbana for the job.

No More Limits

Over the years, Avatar developed a reputation as a publisher of uncompromised, uncensored comics. But in the early months, the company’s books were relatively tame. Avatar Press quickly became known for “nude variant” covers. These are exactly what they sound like: versions of a book that have (usually) female nudity on the covers. It was a concept pioneered by London Night and Lightning, but Avatar kept the idea going even after those two publishers had abandoned it. But apart from nude variants, there was little sex or nudity inside of Avatar’s early books (apart from Donna Mia, which featured full-frontal female nudity in every issue).

But any prudishness evaporated in 1998 when Avatar announced that Faust creators Timothy Vigil and David Quinn, the original Outlaw Comics creators, would do a new series called 777: The Wrath for the company.

Vigil and Quinn had previously self-published Faust and other titles under the Rebel Studios banner. Asked why they went to Avatar in a 1999 interview, Quinn explained:

I guess because William Christensen invited us. He set off to build the home for adult comics that didn’t insult your intelligence — how could he do it without those old bad boys who had set off a whole sub-genre, you know, like the Mick and Keith of comics? I am being glib here, a bit, but the timing was right. Tim and I wanted to play with color and monthly publication, no restrictions except the ones we set ourselves. William needed content. The works that we brought to Avatar were works that we wanted to create on a monthly basis. Monthly, mini-series, the focus was to experiment with simpler story-telling styles… to keep our work out there, to keep it alive, to keep it present.

Vigil told Cartoonist Kayfabe in 2019 that Christensen tried to impose a number of restrictions on the creators when they started at Avatar in 1998, including a ban on depicting genitals. But those restrictions were soon lifted. “I figure if someone’s going to hire me, I’m like a mustang running wild,” Vigil said. “Don’t hold that fucker back, let him do what he does.”

Quinn and Vigil brought several projects to Avatar, including the Raw Media anthology once published by their Rebel Studios.

The Outlaw/bad girl consolidation that started at London Night was by then in full swing at Avatar. Vigil, Wolfer, and the rest of the Avatar stable were drawing increasingly explicit comics, establishing the sort of extreme splatterpunk porn aesthetic the company would come to be known for.

But Avatar hadn’t yet settled on its identity as a publisher of extreme material. In late 1998, they added Dreamwalker to the stable — a significant departure from bad girls comics. “DreamWalker had been at Caliber when they folded,” Barry Gregory tells me. “I pitched it to Avatar but they had zero interest until Sirius wanted to publish it and then Avatar just had to have it.”

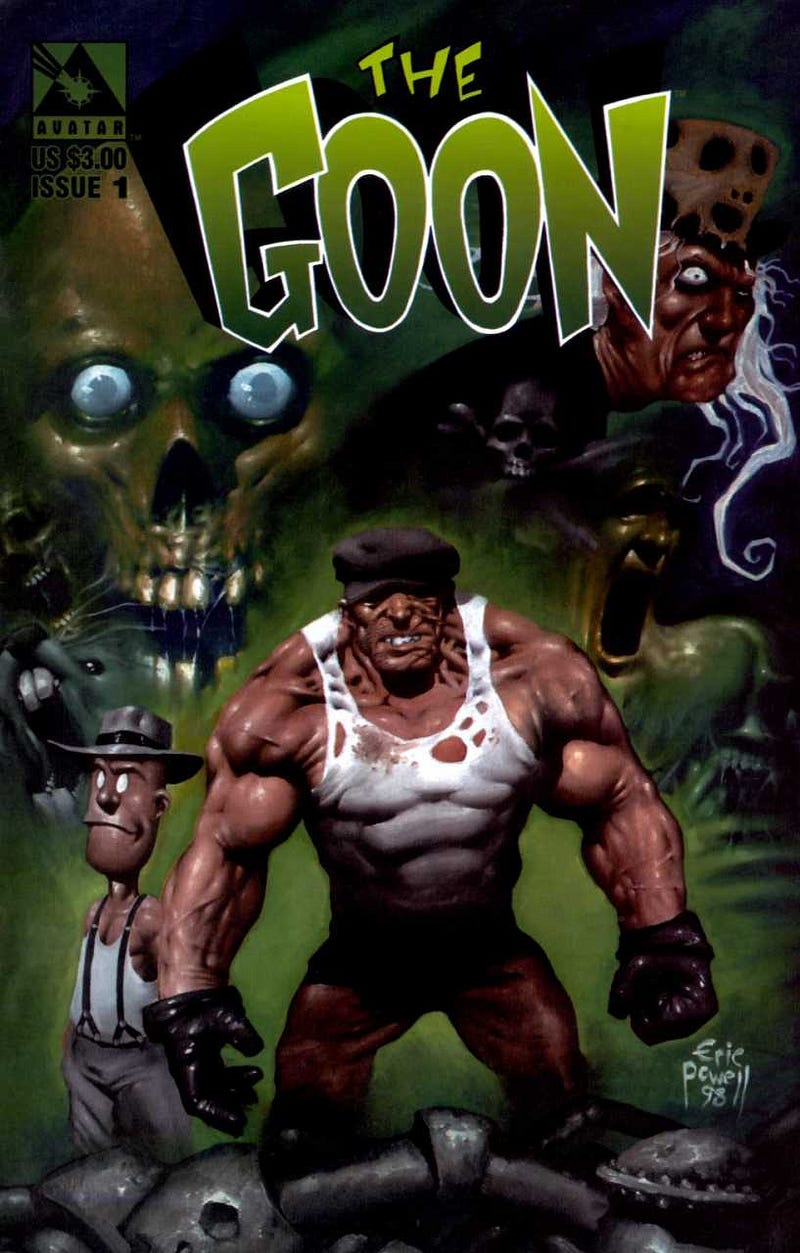

Dreamwalker # 0 (November 1998) also featured the debut of The Goon by Eric Powell, another London Night (and Best Cellars) alum. The Avatar “e-zine” proclaimed:

Avatar shocked its critics with the announcement that we were expanding our horizons beyond the adult adventure / erotic horror / monsters & mayhem comics that we do better than anybody else with the addition of DREAMWALKER to our line.

Make no mistake, Avatar will always be THE publisher who combines quality with balls when it comes to the kind of material we’ve set the standard for over the past two years, but quite frankly, we think we can give the Strangers in Paradises and Johnny the Homicidal Maniacs of the world a run for their money too.

The Goon # 1 was Avatar’s third best-selling title in March, 1999. “Dreamwalker and The Goon both got good reorders which no other titles did,” Barry Gregory says. “By today’s numbers, they would have been big hits.”

But this new direction for Avatar didn’t last.

On the Map

In 1999, Avatar announced it would publish Strange Kiss, a mini-series written and created by Warren Ellis and illustrated by Wolfer.

Ellis was disgraced last year when a staggering number of women accused him of sexual misconduct dating back to the 90s. But in 1999, Ellis was at a high point in his career. He was fresh off runs on Excaliber and Wolverine at Marvel and a blockbuster (though now largely forgotten) Wildstorm series called DV8 for Wildstorm. Meanwhile, he was writing two career-defining series of his own invention, Transmetropolitan at Vertigo and Planetary at Image.

“As a creator, I go to different publishers in search of different things, for each publisher has its own culture,” Ellis said in a press release at the time. “What does it say about Avatar, then, that I go there when I want to write stories about old men giving violent and horrible birth to hundreds of baby lizards through their anus? I’ve worked in black-and-white before, I’ve worked with indy publishers before. Avatar looked to me to be the only place to go. Able to encompass both Jenni Gregory on the one hand and David Quinn & Tim Vigil on the other, Avatar seems to me to be primed to become a breakout publisher.”

A few months before Strange Kiss was announced, DC Comics canceled an issue of Hellblazer written by Warren Ellis and featuring a school shooting. The issue was written before the Columbine shooting that year, but DC management felt it would be in bad taste to publish it. Ellis quit the title in response. I’ve seen speculation that Strange Kiss, starring “combat magician” William Gravel, became a vehicle for Ellis’s Hellblazer ideas, completely uncensored. But Wolfer wrote in 2007 that Strange Kiss was actually a retooled “SATANA script previously rejected by Marvel Comics. Apparently, the story’s concept was just too graphic for their delicate readership. But Warren knew that at Avatar Press, anything goes.”

Ellis put Avatar on the map. The company published many titles by Ellis over the years, and many other critically acclaimed writers would later use Avatar as a venue for their most twisted or controversial ideas. But it would take time for that side of Avatar to develop. Things didn’t always go smoothly in the meantime.

The Comics Journal #215 (August, 1999) printed accusations that Avatar had published work by a freelancer without paying him for it. Christensen told the Journal that Avatar, which for many years included its lawyers on the masthead on the inside front cover of its titles, planned to sue the freelancer in question for breach of contract and slander. The situation ended in a stalemate. The freelancer never got paid, but Avatar never filed suit.

Gregory resigned his post as managing editor over the ordeal. Jenni Gregory and Eric Powell left Avatar when their contracts were up.

I Want Moore, Moore, Moore

Despite these issues, and the harsh market for independent comics, Avatar kept expanding even as the comics market continued to crumble. In 1999, London Night Studios folded and Avatar announced it would publish a new line of comics company’s flagship series Razor after London Night’s founder settled litigation between the two companies. Avatar’s dominance of the bad girl comics market was nearly complete.

In 2000, Avatar inked a deal to publish bad girls titles previously published by Image co-founder Rob Liefeld’s defunct Awesome Entertainment company: Avengelyne and The Coven. That opened the door to a bigger get for Avatar: unpublished scripts by comic book legend Alan Moore.

Liefeld hired Moore to write several series in the mid-90s, including Youngblood, Glory, and Supreme. But Awesome Entertainment shuttered before they could all be completed (Moore took many of his unused ideas to his Wildstorm imprint America’s Best Comics). In 2001, Avatar acquired the rights to complete and publish Moore’s three unpublished issues of Glory — with permission and involvement from Moore himself.

In an interview in 2001, Liefeld explained:

We’ve had different offers from different people to do different books. Avatar came with an aggressive plan for both. I figured they’re the ones that want these books. […] The guy has the right passion and the right network to do it. The guy has the desire. Most of it’s desire. It’s great. It keeps the properties out there, when otherwise, they wouldn’t be published.

Glory was the beginning of a long relationship with Moore, who soon allowed Avatar to publish adaptations of his prose and song lyrics, as well as to reprint A Small Killing, his graphic novel with artist Oscar Zárate.

Meanwhile, more high-profile creators came to Avatar seeking a permissive publisher. Garth Ennis and John McCrea brought their series Dicks to Avatar in 2002, Mark Millar brought the company Unfunnies in 2004, and Jamie DeLano launched his Narcopolis series in 2008.

Avatar kept publishing bad girls comics, adding the icon Lady Death to its line in 2005, and also began adding licensed comics to the mix, ranging from Stargate to Night of the Living Dead. But it became best known for its creator-owned series.

The late 00s/early 2010s was a particularly fruitful period for Avatar. Ellis’s Black Summer, a story about a superhero assassinating the President of the United States, garnered mainstream coverage in 2007, including a cover story in American Prospect magazine. Avatar played host to many experiments by Ellis during this period, including a “pop-up label” called Apparat, the webcomic series Freak Angels, the web forum White Chapel, and a science/technology/culture group blog called Grinding, launched to promote the Doktor Sleepless series.

Meanwhile, Ennis and Jacen Burrows (another former London Night freelancer) launched Crossed in 2008, kicking off what became a long-running franchise at Avatar. Television writer Christos Gage wrote a series called Absolution. And, faced with an unexpectedly large tax bill, Moore agreed to do an entirely new book for Avatar in 2010: the Lovecraftian Neonomicon with Burrows.

Burrows recalled his time with Avatar fondly in an interview with The Comics Journal last year. “It wasn’t always the content I wanted to work on, but that changed early on,” he said. “From there it was as good a working relationship as one can have. There was never a gap in interesting projects with top tier writers and they continued to raise my page rate every contract until I was making rates as good and sometimes better than Marvel or DC offer. I even got health insurance for a time, which was unheard of for freelancers in American comics, especially indie comics.”

In 2010, Avatar created a new imprint called “Boundless Comics” for Lady Death and other bad girl comics. With the bad girls cordoned off, Avatar’s main stable of titles looked more and more like a grosser version of Vertigo, adding more series by the likes of Kieron Gillen, Jonathan Hickman, and David Lapham while kicking up controversy over their latest gimmick: the “torture variant” (a new, more extreme spin on the gruesome Deadworld variants published by Arrow and later Caliber in the 1980s).

But the trickle of comics from both Avatar and Boundless has slowed over the last few years. Avatar lost Lady Death around 2014 following a legal battle with creator Brian Pulido. Moore completed his Neonomicon sequel Providence in 2017. His anthology Cinema Purgatorio published its final issue in 2019. Moore claims to be done with comics entirely. The Crossed saga came to an end with Crossed +100: Mimic in 2018 and Stitched, another Ennis franchise, wound down in 2019. No other Ennis work for Avatar appears forthcoming at press time. I don’t think Ellis has published a book with Avatar since Gravel: Combat Magician in 2014. Gillen’s Uber: Invasion has been stalled for years, leaving fans to speculate that the company is having financial problems. The two artists most associated with Avatar, Juan Jose Ryp and Jacen Burrows, have left the company for more mainstream publishers. Wolfer and former Avatar managing editor James Kuhoric have jumped ship for American Mythology. Instead of publishing through Avatar, many bad girl series, including a relaunch of Razor, have opted to raise funds through Kickstarter.

Avatar thrived during some of the leanest years the comic book industry ever faced, but as the industry racked up record sales, Avatar has shrunk. As far as I can tell, Avatar only published reprints in 2020. But there are signs of life. Avatar ran a successful Kickstarter last year for the forthcoming collected edition of Providence. Bleeding Cool continues apace, and, in addition to various reprints, a Nightmares of Providence pin-up book is slated for April along with a new Jungle Fantasy series scheduled to ship from the Boundless line.

With their past now demystified, Avatar’s future is now its biggest mystery.

If you want to follow this series, follow Sewer Mutant here on Medium, or subscribe to my email newsletter:

Corrections and additional information can be sent to klintfinley@gmail.com. Would love to hear from anyone who’s worked with Avatar Press. And William, Mark, I’d obviously still love to hear from you guys, I’m sure there’s quite a bit that could be filled in.