Grips and The Early Works of Joe and Tim Vigil

Wave of Mutilation Part 1: The Birth of Rebel Studios

Wave of Mutilation Part 1: The Birth of Rebel Studios

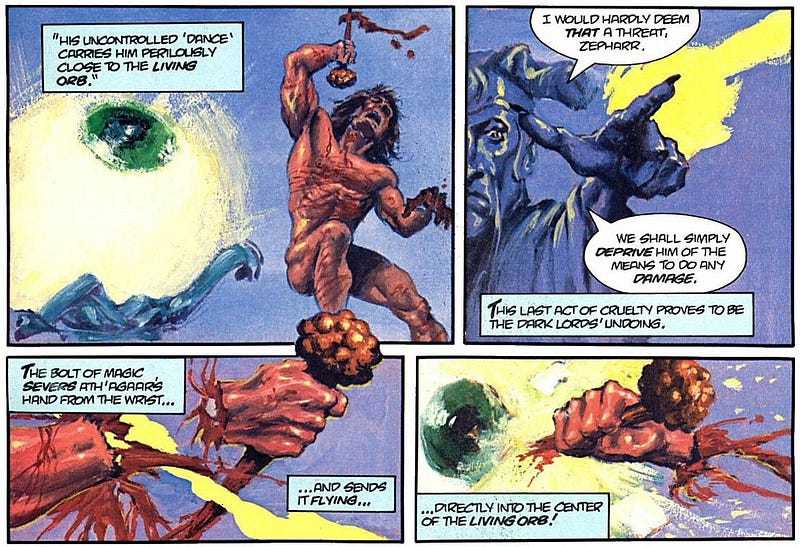

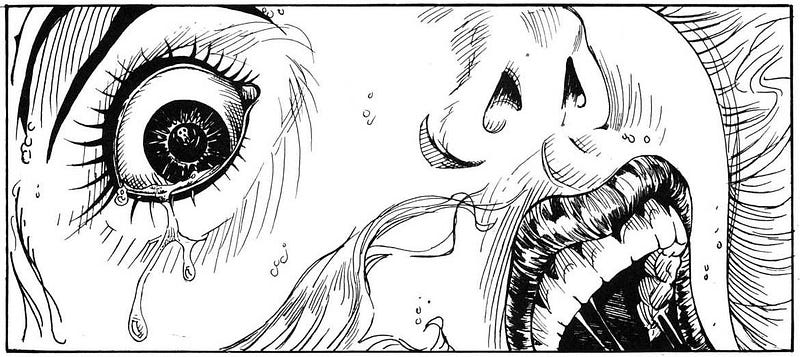

Tim Vigil cleaved his way into public consciousness with Grips # 1 in the fall of 1986, around the same time as Watchmen # 1. The artist announced his arrival with a double splash page — aggravatingly split into two frames — highlighting what has become the hallmarks of his work: sex and violence.

In that spread, vigilante protagonist Grips caves in the face of one mugger/rapist with his boot while he shoots another through the eye with a projectile. Gore sprays everywhere while the criminals’ intended victim flees, her dress pulled up and leaving little to the imagination.

It’s a pretty good candidate for “First Outlaw Comic.” Grips writer and publisher Kris Silver was unapologetic about the content. In response to a reader letter complaining about the “sexual overtone” in the first few pages of issue 1, Silver wrote: “They’re not meant to be overtones but rather a major aspect of the book. If you have never encountered the harsh reality of vicious crime then perhaps you don’t understand.”

Despite the misgiving of that particular reader — who clearly hadn’t seen nothin’ yet — fans ate it up. It was perhaps Grips, even more so than Rorschach or The Punisher, who set the mold for the wave of hyperviolent vigilante comic book characters that followed over the next decade and a half.

It was the right comic at the right time. As crime rates surged in the 1970s and 1980s, film and literature responded with increasingly violent fare, from Dirty Harry to Death Wish to Ms. 45 to Scarface to Rambo 2 — to say nothing of slasher films. Meanwhile, authors like Jack Ketchum and Clive Barker pushed boundaries with the printed word. But few were whetting comic fans’ bloodthirst.

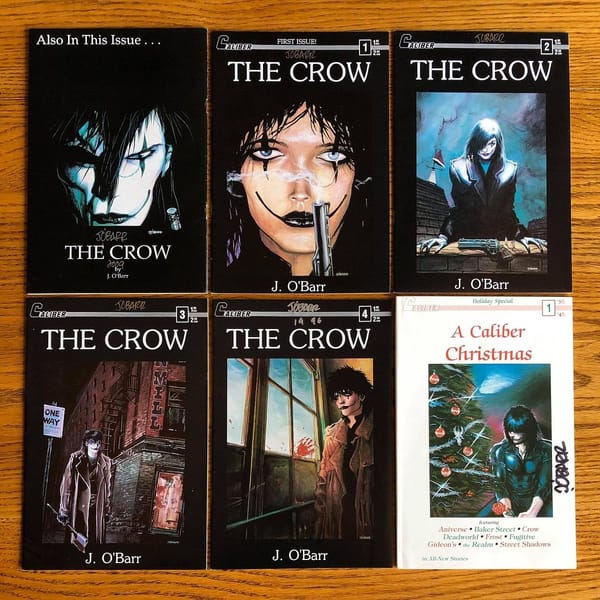

Given the buckets of gore served up in the following decade by artists like Todd McFarlane, Rob Liefeld, and of course Vigil himself, it’s easy to underestimate just how hemophobic the comics industry was when Grips arrived. Sure, the Underground Comix movement had already shattered many taboos, but undergrounds were in steep decline by the mid-80s. Warren Publishing’s Creepy and Eerie were cancelled by this time. And although the emergence of the “direct market” (ie, selling comics directly to specialty shops, as opposed to newsstands, grocery stores, and the like) opened the floodgates for comics not bound by the stringent rules of the Comics Code Authority, such as American Flagg and Sable, the industry was still quite squeamish. They were trying to walk a fine line between appealing to older readers while still ensuring that books could be sold to minors.

For example, just two years earlier, Marvel published Steve Gerber and Val Mayerik’s Void Indigo, a Richard Corben-esque science-fantasy/barbarian story, under the Epic imprint. Retailers, distributors, and critics found Void Indigo outrageously violent and sexual. “One distributor expressed dismay that Marvel wouldn’t allow the comic book to be returned for credit: ‘Marvel feels [retailers and distributors] were sufficiently warned about the book’s contents, but they didn’t tell us it was going to be grotesque,’” Keith Dallas wrote in American Comic Book Chronicles: The 1980s. Copies of Void Indigo were seized by Canadian customs for potentially violating pornography laws (a frequent problem for comics in the 80s and 90s). The series was canceled after only two issues.

In 1986, retailers and distributors revolted over the graphic depiction of childbirth in Miracleman # 9. “Miracle Man (sic) # 9 was the straw that broke the camel’s back… It appears to be a classic case of poor judgment (not to mention poor taste) on the part of the publisher, when right above that warning label is the slogan proclaiming Miracle Man # 9 to be American’s number one Super Hero… what is the purpose of this outrage?” Dallas cites Diamond Comics Distributors owner/CEO Steve Geppi writing at the time.

But that year was a turning point. In addition to Watchmen, DC published Howard Chaykin’s gory Shadow reboot, Frank Miller’s instant classic Dark Knight Returns, and the considerably more tame but still controversial Superman: Man of Steel by John Byrne. The sales and media attention these titles generated guaranteed that, after the near extinction of adult-oriented comics following the Underground Comix explosion and implosion, “mature readers” comics were here to stay.

Tim Vigil, his brother Joe, and writer David Quinn would be at the forefront of this comics revolution well past the year 2000.

Early Years

The Brothers Vigil were born in the 1950s and grew up in Sacramento California. They’re lifelong comics fans and artists. “I had complete sets of Spiderman and Daredevil,” Joe says. “And I do mean complete, from issue one up to when I left for the Air Force. I sold them all before I left. Dumbest thing I ever did in my life.”

The duo often drew comics together as kids. “[Joe] was always very intuitive,” Tim told Cartoonist Kayfabe. “He could sit down and draw a page and I’d go ‘that’s fuckin’ awesome.’” Tim, however, struggled to draw from his imagination and mostly copied artwork from comics by the likes of Neal Adams, Bernie Wrightson, and Berry Windsor smith. In high school, however, Tim decided that if he really wanted to be an artist he needed to stop copying and start working on his own images. “By the time I was a senior I was doing some pretty neat stuff,” he says.

Both Vigils attribute their fascination with blood to seeing Wild Bunch in the theater as kids. “I learned to draw blood because of the Wild Bunch, that movie changed my life,” Joe says. “We made my mom sit through that twice, she hated that movie.”

“It was like heaven: the clouds opened up and the angels were singing to us,” Tim told Cartoonist Kayfabe. “That’s where the splatter comes from.”

As much as they liked Marvel, they also developed a taste for Underground Comix in their teens. “There was a headshop pretty close to our house, before I went into the service,” Joe explains. “We went in there looking for blacklight posters and we saw these comic books. Richard Corben blew our minds. It was so different from what anyone else was doing.”

“I was glued to [Corben’s] comic art,” Tim told Comics Tavern. “Big tits shaking and fat wang flopping about. I saw a road to travel on. A less road traveled and full of danger.”

Tim told Kayfabe he was also heavily influenced by the Underground Comix of Greg Irons and Tom Veitch, particularly “Cleanup Crew” from Skull Comics # 3, which featured a couple having sex on a pile of severed body parts (“I couldn’t believe it. It was great but it horrified me, Marvel comics never had that impact on me.”), and “Homesick” from Slow Death # 4, where a man is stranded on a planet of ugly, mutated people. Underground comics showed him that “this idea of dementedness could really go somewhere.”

The brothers also grew up against the backdrop of the Vietnam War and all the carnage that ensued. After high school, Joe enlisted in the Air Force, where he became a medic. “I was going to be drafted, so I signed up so I wouldn’t be sucked into the Army,” he explains. Fortunately, he wasn’t stationed in Vietnam.

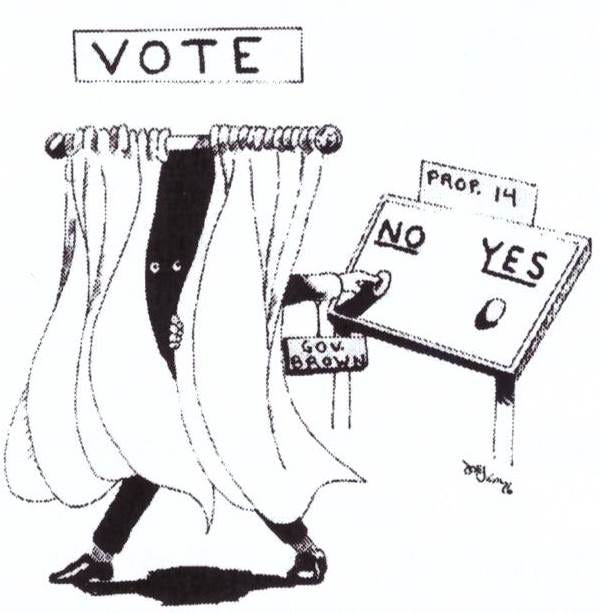

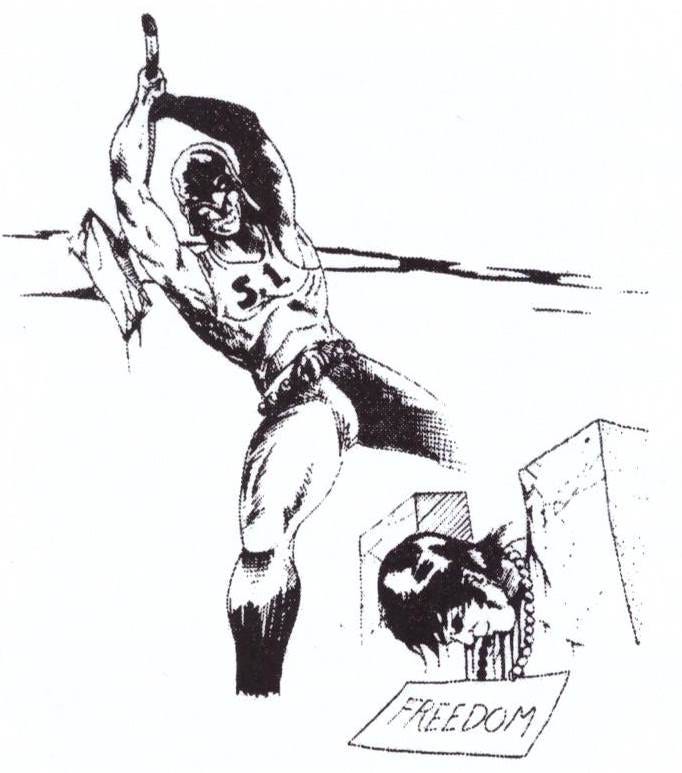

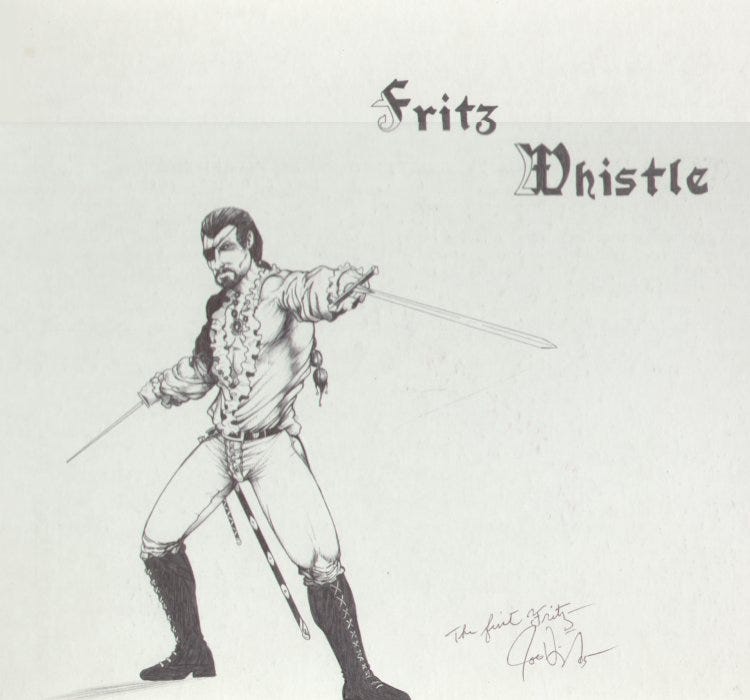

After his service, Joe kept making art. He drew comics for a newspaper called Cartoon Art in 1976, cited as his first published work in Vigil Saga by Glen Hammonds, and contributed one-panel political cartoons to the American River College newspaper Beaver in 1976 and 1977. The first published drawings of his barbarian character Fritz Whistle also appeared in Beaver. One of his political cartoons, more representative of his future work, appeared in the Journalism Association of Community Colleges’ All State Newspaper in 1977 — possibly a reprint from Beaver. Some of this may have been reprinted in the equally rare Joe Vigil’s Lost Works from Raw Comics in 2005.

Tim gradated high school sometime around 1976 and went on to college, where he took art classes but didn’t major in art. In 1977, the brothers took a trip to New York. They stayed with their sister and her husband in New Jersey while Joe showed his portfolio around to comics publishers. “I went to see Neal Adams at Continuity,” he says. “I got to meet Russ Heath. I went to Warren comics around that time, lots of places. But only Marvel called back.”

“I went to see John Romita who was the head of art at Marvel back then,” Joe says. “The security people were shocked that I got in, they hadn’t let anyone in to see him in weeks.” Romita encouraged Vigil to look at John Buscema to improve his anatomy. But the trip was soon cut short as tensions between his sister and her husband boiled over. “I don’t regret not working for Marvel,” he says. “But it would have been interesting. It’s too bad you couldn’t send art over the internet back then, you had to live in New York.”

By 1981 he and Joe were both contributing covers to a Sacramento newspaper called Weekly Aardvark. The first seven issues had covers by Joe, Tim, or Joe and Tim together. They contributed covers sporadically to future issues.

In 1983, Rebel Studios debuted with the original run of Raw Media Mags, a tabloid-sized, photocopied zine published by the Brothers Vigil. Only 25 copies of each of the three issues were printed, according to Vigil Saga. The brothers collaborated on the first issue’s cover. The third and final issue had a cover by John Palmer and the first appearance of Joe’s beloved character Dog.

Tim made one last notable appearance before his stint at the publisher that propelled him to fame. In 1985, he drew the cover of Access Sacramento Fanzine # 1 and contributed several drawings, including the first published drawing of his own barbarian character Cuda. The issue also features art by Palmer and fellow Sacramento artist and The Maxx creator Sam Kieth.

SilverWolf

Tim got his big break in comics when some guys from his bowling league told him about a new comics publisher in Sacramento, he explained to Kayfabe. Tim Foster told him he’d walked into Kris Silver’s store Alexander Comics looking for a job writing for SilverWolf. Silver hired him as an artist instead. “I said, ‘shit, I can get a job here,’” Tim recalled. “I went in and Kris Silver said ‘I’m gonna put you on my best book: Grips.”

Silver — who Foster once described as a “strange, nunchuck-wielding nerd” — launched Silverwolf in 1986 to publish The Eradicators, a series drawn by Ron Lim, who went on to draw titles like Captain America, Silver Surfer, and Infinity War at Marvel. This was the height of the black and white boom spurred by the success of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, when unknown small press publishers frequently sold through print runs of tens of thousands of copies. “Elfquest was a great inspiration to me and made me realize that comics weren’t just for the big companies. Us ‘little guys’ could make comics, too, if we wanted to,” Silver wrote on his website. “I wanted to.”

Silver really did want to. He built SilverWolf into a mini-empire, publishing multiple titles, along with tabletop games and computer games. Titles ranged from superhero stories like The Eradicators and Fat Ninja to fantasy series like Dragon Quest and Dungeoneers. “I had expected a nice little print run of about three to five thousand orders for the first Issue of Eradicators. I got twenty thousand. Just a few more than I expected! The first issue of Fat Nina did better,” he wrote.

Silver struggled to find enough talent to produce all the comics he was publishing. For example, SilverWolf hired Rob Liefeld to draw a title called Stech after Silver apparently had issues with the previous artist. It would have been Liefeld’s first professional work, but he soon landed his first assignments at Marvel and left Stetch unfinished. Lorenzo Lizana ended up drawing the book.

Amidst this chaos, Tim proved to be a workhorse for SilverWolf, drawing multiple books including Dragon Quest and Night Master. But Tim left SilverWolf after Grips # 4 (Cover date December 1986) due to payment disputes and concerns about the quality of the product. “SilverWolf didn’t care, he didn’t care how it looked, people were buying it,” Tim told Kayfabe. Indeed, there was a marked decline in quality after Grips # 1, which I think Tim inked himself before handing inking duties to Palmer and others, though he admitted that he was phoning it in by the end of his stint at SilverWolf.

SilverWolf shuttered not long after. “I knew that the market would wane, eventually,” Silver wrote. “I did not want to get caught in the backlash so I refrained from putting out any ‘fuzzy animal’ or multi-worded anthropomorphically titled books. It didn’t matter. Silver Wolf was crushed under the ensuing torrent of rage from cynics and angry speculators.”

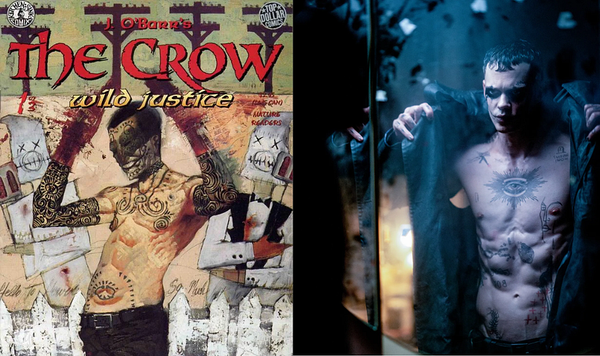

Meanwhile, Wouk Baez, a New York City comics retailer who was starting his own publishing venture, visited Sacramento and struck a deal with Tim to publish a new series of Tim’s own creation. That would lead Tim to his partnership with David Quinn and, later, their most famous and infamous creation.

Faust/Rebel Studios Series

Part 1: Grips and The Early Works of Joe and Tim Vigil

Part 2: The Birth of Faust: Love of the Damned by Tim Vigil and David Quinn

Plus: More from the Outlaw Comics series

If you want to follow this series, follow Sewer Mutant here on Medium, or subscribe to my email newsletter: